Elinor Jan Goulding (1917-1978) married Robert Paul Smith (1915-1977) in 1940. Elinor knew Robert wrote. Just a year later a novel, clumsily titled So It Doesn’t Whistle, was received with open arms, many predicting that the budding author had great promise. Elinor was right behind: her essays began appearing in The Atlantic in 1943. A long apprenticeship followed; neither achieved real fame for more than a decade. They never wrote together, each following a separate path. Yet by 1958 the pair had such national status that Edward R. Morrow considered them suitable for a joint interview on his uber-prestigious television show, Person to Person.

Yet forgotten barely begins to describe them, especially Elinor, who has all but been disappeared from history. The poor-quality newspaper picture above is the only published picture of the duo I’ve been able to find. Wikipedia has a sparse page about Robert, giving no information about his family. Elinor doesn’t get a page at all. There or anywhere else. Her birth and death dates are from her Amazon biography, and otherwise unsourced. No papers were kind enough to give a capsule biography in her obituary, because her death, whenever it was, went unnoticed. She could be in a home somewhere, a youngish 108-year-old, laughing that the reports of her death were greatly exaggerated. All I have to go by are scraps and inferences and glints of her early life included in humorous essays, which are notoriously as trustworthy as CIA operatives.

So let’s take Elinor first and give her, if not a proper biography, as much of one as the data permits.

Elinor Goulding Smith

Elinor Jan Goulding was born in New York City, and attended P.S. 6 and the Julia Richman High School. The latter in those days was an all-girls high school. Although she had no high school diploma, she spent two years at Cornell, a would be Class of ‘36 graduate.

I had left college under a tiny cloud. This little cloud had nothing to do with my grades, which were excellent, or my behavior, which was lovely. It seemed that nice Cornell girls did not appear on campus (where there were men) without stockings, even if they did have a sunburn and gangrene setting in on the backs of their knees. Nice Cornell girls do not slide down the hill on their rear even if the hill was covered with ice and they fell.

Class of ’36 implies that Elinor would have graduated when she was 19 and therefore she was a prodigy who entered Cornell at an unusually young age. The math works out. In one essay she says she entered high school at the age of 12. In three years she completed all the courses necessary for college. But not a diploma. That would have required a fourth year of “rope climbing and Highland Fling.” She didn’t care and neither did Cornell, where she apparently entered as a fifteen-year-old Freshman, making her 19 after a standard four year degree. She was indeed very smart, along with being very tall (5’8”), very non-athletic, and very unlike her three-year-older sister with the curly blonde hair and conventional interests that she contrasted herself against for comedic self-deprecation. Elinor’s hair was dark and straight and unruly. Her parents, also comedically cast as villains, thought she would never get a husband.

For several years she didn’t. Elinor harvests her succession of menial jobs for more self-deprecatory humor in her essays. Reality must be been stinging. The Depression was still a factor in most lives, even those of the middle class family she was born into. Untalented as a clerk, she completed a secretarial course at Interboro Institute of Secretarial Training, a place that sounds made up but isn’t. Tuition for a 30-day cram course was $65.

In real life, not fodder for her essays, she also attended art school and worked as an artist. Then, at a fateful party, she locked eyes with Robert Paul Smith, who thought she was a completely different girl. Perhaps that was why he called her for a date and presto: “love at second sight.” Marriage immediately followed, on January 7, 1940. Two babies ensued, Daniel and Joseph, less immediately, both after the war. Current Biography’s 1958 volume says that Daniel was age twelve and Joseph age ten, so 1946 and 1948 for birth dates. Joseph became a concert pianist and has his own Wikipedia page, longer than his father’s, confirming the 1948 date. Daniel became a zoologist. Elinor would eventually use her artistic training to illustrate two books, one of her and one of Robert’s. A wife illustrating her husband’s best seller. You can see how a tv show might build a segment around that.

But that’s a way away. Elinor had to be patient. Not unlike Jean Kerr, whom she would be compared to, Elinor was catapulted to nationwide fame overnight after a long decade’s slog.

Aside 1: Comparing Elinor to Jean seems almost mandatory. Elinor was born in 1917, Jean in 1922. Elinor married a writer at a young age, Jean married a writer at a young age. Both lived with kids in crowded Manhattan apartments until they left for the suburbs, Elinor in Scarsdale, Jean in Larchmont. Elinor had two boys, Jean had five boys … and then a girl. Elinor wrote about the trials of being a housewife, Jean wrote about the trials of being a housewife. Elinor also wrote works totally aside from women’s issues, like parodies of popular works, Jean also wrote works totally aside from women’s issues, like parodies of popular works. Elinor tried to break out of the housewife trap, Jean tried to break out of the housewife trap. Elinor was tall, Jean was even taller. Jean gained some fame and money by writing a play that was turned into a movie. Elinor, well, Robert gained some fame and money from writing a play that was turned into a movie. Elinor typed her husband Robert’s handwritten manuscripts, Jean’s handwritten manuscripts were typed by her husband Walter. I could go on for days. The important point is that while Elinor and Jean wrote on similar subjects, sometimes making similar complaints about similarly cliched subjects, their work sounded nothing alike. They were individuals who happened to overlap. (Did they ever meet? There is no record.) Their public similarities were almost entirely due to the way they were similarly hemmed in by the expectations of women in the 1950s.

To Robert’s chagrin, Elinor sold the first piece she ever wrote, to the Atlantic magazine of all non-humorous places. Another half-dozen pieces appeared before Daniel’s birth. That slowed her down a tad but another half-dozen followed.

From an occasional essay she, yes, became famous overnight by writing for another magazine… well, let me quote the first newspaper mention of her name I can find, that in 1956, featured in the February 28 Garden City [KA] Telegram in a column on the front page.

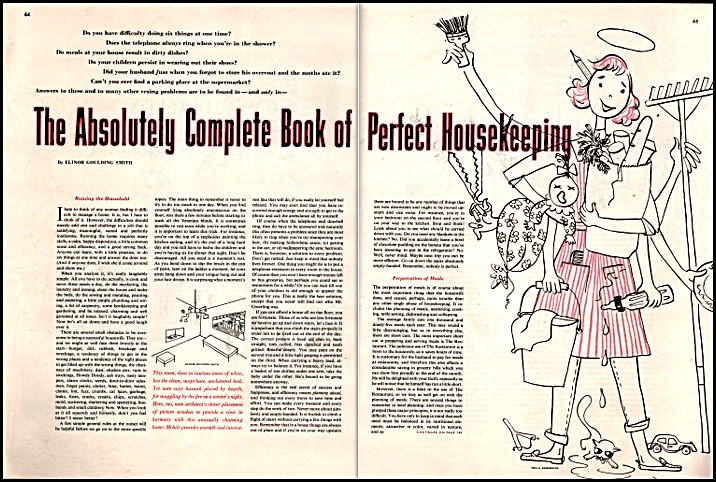

For a while last night, it appeared that we would need a psychiatrist up at our house to calm our wife’s hysteria. Turned out, however, that she was simply reading an article in the March Ladies Home Journal by Elinor Goulding Smith. “The Absolutely Complete Book of Perfect Housekeeping,” in which as the Journal says, the housekeeper bites back. It is, indeed, a perfect answer to all those advice columns on how to be sweetly calm when the small fry run the water over the bathtub.

Aside 2: Let me pause for a second to fill you in on women’s magazines in the 1950s. They were powerhouses, with large circulations and devoted readers. They were literally large, as well. The Journal measured a whopping 13 ½ x 11 inches, 40% larger than the standard size, 8 ¼ x 11 inches, of say, Playboy. The March 1956 issue contained 226 pages; the March 1956 Playboy only 72. It contained lifestyle articles with layouts as luscious as those in Playboy, yet readers of both could legitimate claim they read them just for the articles, presented by the Journal in tiny type, meaning they could cram several books’ worth of text between two covers. That March issue contained a complete novel condensation, a serial, two stories, seven poems, and eleven features in addition to Elinor’s. That count doesn’t include the Fashion and Beauty, Food and Homeworking, and Architecture, Gardening, and Interior Decoration sections, with 13 more articles. If you had time left before the end of the month, a dozen or so regular columns awaited. Total: more than 30 times the length of this long biography. Imagine reading that much text online, month after month, from half a dozen major general magazines and many more specialized ones.

Elinor begins with a joke whose construction would be echoed by dozens of later stand-ups. “I hate to think of any women finding it difficult to manage a home. It is, but I hate to think of it.”

The next paragraph sums the book.

When you analyze [housekeeping], it’s really laughably simple. All you have to do, actually, is cook and serve three meals a day, do the marketing, the laundry and ironing, clean the house and make the beds, do the sewing and mending, painting, and papering, a little simple plumbing and wiring, some bookkeeping and gardening, and be relaxed, charming and well groomed at all times. Isn’t it laughably simple? Now, let’s all sit down and have a good laugh over it.

The timing was perfect. People concentrate on the baby half of the baby boomers, ignoring that a boom in marriages must have preceded the babies. At least in theory. 1946, the first year of the baby boom, had the highest marriage rate in U.S. history. Over two million marriages took place that year and in 1948 (just missed in 1947). Not until 1968, with a much larger population, would America see that again. Moreover, the average age of first marriage for women from 1946-1956 was a hair over twenty. The majority of young brides moving into new homes with their husbands needed advice about every aspect of housekeeping. A decade’s worth of self help articles and books were ripe for satire.

“Elinor Goulding Smith should be the ideal of every red-blooded, dishpan-pawed, sacroiliac straining American housewife,” wrote columnist Clarissa Start. Housewives all over America laughed until they cried, sometimes vice versa.

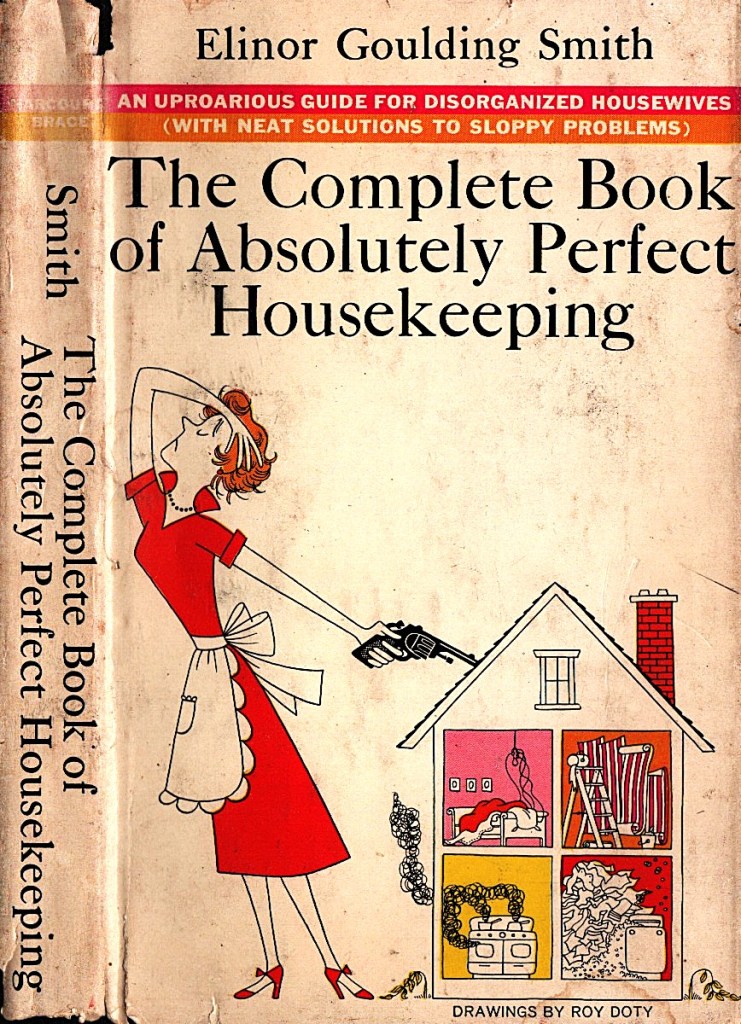

A hardcover book might seem superfluous after millions of women – Journal’s circulation was 4.6 million with more than twice that many readers – had a chance to read the almost complete book – a skillful editor removed a few paragraphs and sentences here and there. Although the Journal piece drew a remarkable number of reviews and mentions for a mere magazine article, the ecosystem of books ran on different tracks from that of magazines. When the hardback appeared in October, reviews vastly outnumbered the earlier articles. All I found were complimentary, sometimes hyperbolically. “[T]here isn’t a perfect housewife anywhere who won’t scream with laughter after just one page of the sort of thing we’ve quoted.” Probably because so many had already read it, the book did not make either the New York Times or Publisher’s Weekly best sellers lists. Many later references nevertheless talked about it as a bestseller. Very possible: dozens of lesser best sellers lists appeared in newspapers and magazines, and the book could have hit hard locally.

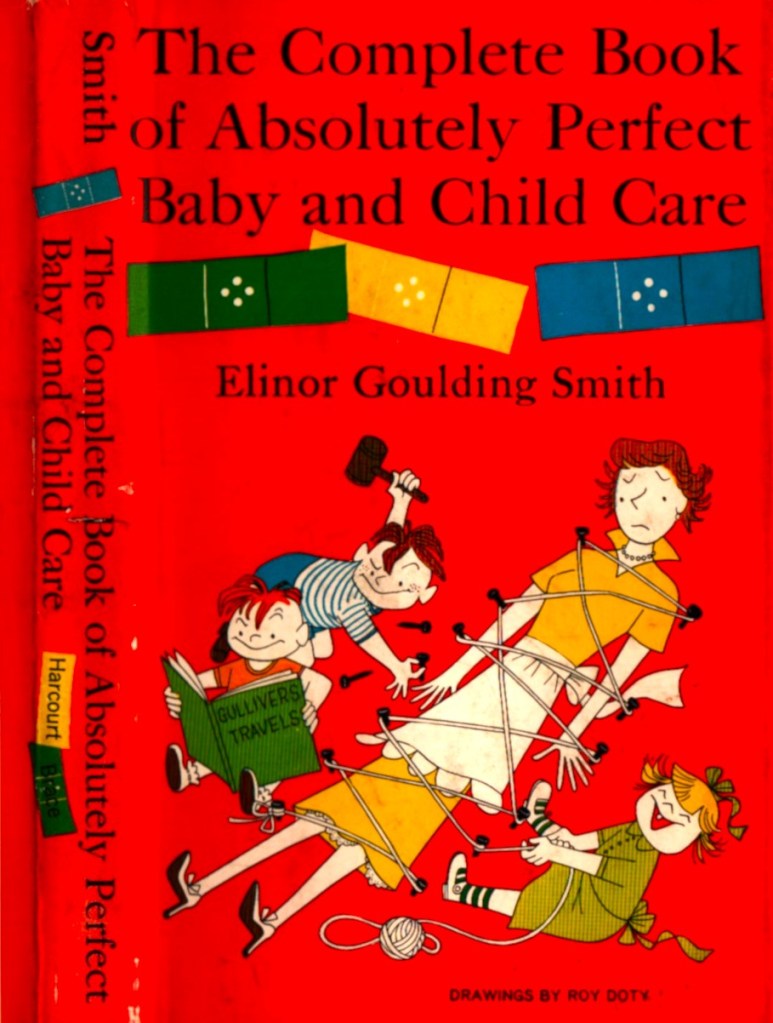

Anywhere in the country, in fact. Local reporting remained a mainstay, especially in smaller cities and towns. A myriad of newspapers reported that a women’s club had made Elinor’s book the subject of a meeting. Astonishingly, reports of this continued in newspapers until September of 1957. Double astonishingly, not just for the length of time but because the Journal and Elinor seemingly preempted themselves that March. The inevitable sequel appeared in the Journal’s March 1957 issue: The Complete Book of Absolutely Perfect Baby and Child Care. Mentions in newspapers were a small fraction of the earlier books’. Most again cited the opening line, “It sometimes happens, even in the best families, that a baby is born.”

After the hardback appeared in the fall, reviews, equally hyperbolic in their praise, poured in, like this one by the acronymistic H.E.G. in the Chicago Tribune.

[M]y wife pinched the review copy before I had a chance at it. … [S]he was laughing so hard that all I could make out was something about hamsters.

I will qualify her as an authority and accept her word that the book is completely and absolutely funny.

Aside 3: Note that this review and another above are men talking about the reaction of their wives to Elinor’s books, apparently having not read them themselves. Male columnists outnumbered female columnists by a large percentage in the 1950s. That’s not to say that men didn’t read the books and review them favorably and that women didn’t gush all over them, just another fact about the era. Housework was women’s stuff, and baby and child care even more so. Men may have occasionally mentioned the subjects but male humorists had the entire world as potential subjects. If women wanted to be humorists, their horizons were more limited. Jean Kerr wrote about children, housekeeping, and marriage and in 1957 would become famous for doing so with her essay collection Please Don’t Eat the Daisies. Cornelia Otis Skinner, an actress who was the leading woman humorous essayist before Jean and Elinor, started her career in 1932 with Tiny Garments, blurbed as “the Complete Lowdown on Expectant Motherhood”. A decade later, reporter Ruth Dolan, under the pseudonym of Rory Gallagher, turned out Lady in Waiting, a lighthearted diary of her pregnancy. Hildegarde Dolson started her long career in 1938 with How About a Man, better described as how to catch one. Spoiler: she didn’t and returned in 1955 with Sorry to Be So Cheerful, essays about her singlehood. In 1953, the sister act of Grace Klein and Mae Klein Cooper produced the darkly satiric The Unfair Sex: An Expose of the Human Male for Young Women of Most Ages under the name of Nina Farewell. In that seminal year of 1957, Sylvia Wright’s collection of essays, Get Away From Me With Those Christmas Gifts, included “My Kitchen Hates Me.” Betty McDonald had her beat six ways from Sunday in her giant WWII-era bestseller, The Egg and I, an account of her needing to learn how to cook food on a stove she also chopped the wood for and shot the food for when her husband moved her to a off-Seattle island home at age 18. Three sequels, two of them New York Times certified bestsellers, followed. Women sold hugely when given the chance. They seldom were.

Skipping ahead, Elinor’s fourth book, released in 1960, returned to that fenced-in but lucrative province of things women should write about. The Battered Bride was not, as we might assume today, a volume on spousal assault. (Not in those innocent times, surely. On the contrary, a newspaper search for 1960 brought up many headlines about truly battered brides, some battered unto death.) Rather, Elinor wrote about marriage as if she were completing a trilogy of womenstuff.

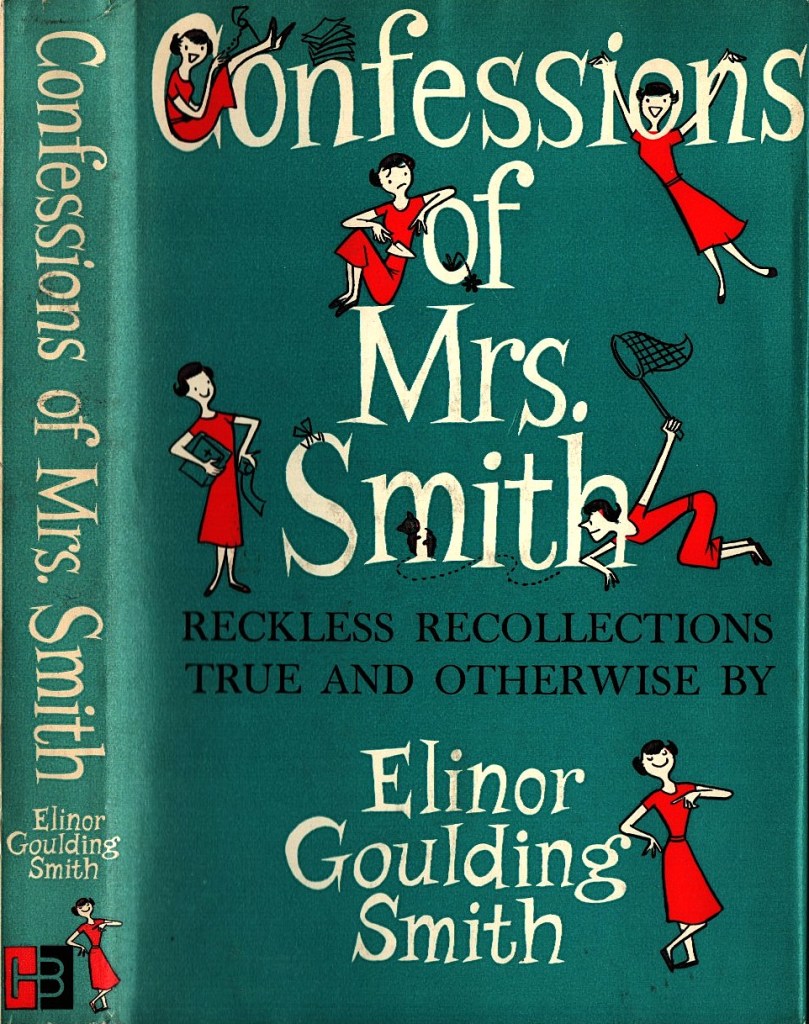

Elinor, as with so many other of those writers I just mentioned, chafed at being assigned to “just” women’s interests. The attitude of the 1950s was so pervasive that it spawned this comment by a women columnist about Elinor’s third book, Confessions of Mrs. Smith. “If she’s not quite as funny in this later book, it’s probably because she’s broadened her field to include such oddly assorted objects as hats, parties, typewriters, and potted plants.” Broadened. Really.

Another woman, Patsi Farmer, wrote bluntly that “It is to be hoped Mrs. Smith never will be passed off with that lethal kiss ‘Writes for women’s magazines.’” Somebody – probably Keith Coulborn, the Sunday Editor – undermined Farmer before she had said a word, putting “Writes for women’s magazine” into the heading.

Of course Elinor wrote for women’s magazines, Redbook, McCalls, Woman’s Day, and Vogue, in addition to the Journal. That’s where the money was. She also had a very serious article published in the very serious Harper’s magazine in her banner year of 1956, one that wasn’t mentioned in later book flap bios.

“Won’t Somebody Tolerate Me?” appeared in the August 1956 Harper’s, subtitled “What happens when agnostic parents try to raise their children without joining any of the organized religious sects…” Elinor made her case based on the supposed rights accorded to every American. “I do want the freedom to think and believe in the way I find right, and I want the freedom to raise my children in my own beliefs.” Clergy responded as if she had dropped a very large stone in their little pond. Any backtalk to the supposition that America was a Christian country disturbed them greatly. Nevertheless, Elinor was in the forefront of asking for a major change in public policy. Religion, at least the sanctioned teaching of a particular religion’s beliefs, was eliminated from schools in a landmark 1962 Supreme Court decision, just as Elinor had asked for. She must have cheered.

Regular readers of The Atlantic grew familiar with Elinor’s name, since after that 1943 debut she returned in 1944, 1945, 1946, 1947, 1950, and 1954. There she had the freedom to write on any topic she pleased, mostly humorously. Most of the information on her early life given here comes from those rueful essays, looking back at a youth full of awkwardness, illness, and disappointments. Even discounting the necessary comic exaggeration, it’s telling that Elinor does not relate a single happy moment before her marriage. All the more so since she lived with a writer who would unexpectedly make his name as the foremost champion of the glories of being young and free.

Elinor’s story is not over. Nonetheless, at this point I have to switch over to Robert.

Robert Paul Smith

Robert’s biography is available on his Wikipedia page and in his newspaper obituaries. Ironically, though we know what he did virtually every minute of his boyhood, we know nothing of his life. Elinor wrote about her childhood and her parents and the outside world. Robert’s world, although he boasted of its openness, was confined in print to the streets and outdoors of suburban Mt. Vernon, NY, and what he and his playmates got up to. Harder to say whether they complemented one another or were mystifyingly different.

He attended Horace Mann School for Boys, a famed prep school in The Bronx, and then went on to Columbia, Class of 1936. He and Elinor would have shared that graduation date if she had stayed on at Cornell. (Columbia was all boys at the time so they never could have been together.) That both went to Ivy League schools during the Depression speaks large to their household status and their intellect. Columbia in particular accepted only one in six Jewish students because of unwritten quotas. They made a good choice in Robert. He earned gold keys for his work on the campus newspaper and rose to being co-editor of the literary quarterly.

After graduate he began a long association with CBS, radio and then television. He worked behind the scenes as a general assignment writer.

I wrote what is called continuity, which is what the man says while the musicians are turning pages. My specialty was making it sound ad-lib. Some of the people for whom I wrote ad-libs were Benny Goodman, Frank Sinatra, Eddy Duchin, Paul Whiteman and Guy Lombardo. This paid the rent while I wrote four novels which did not.

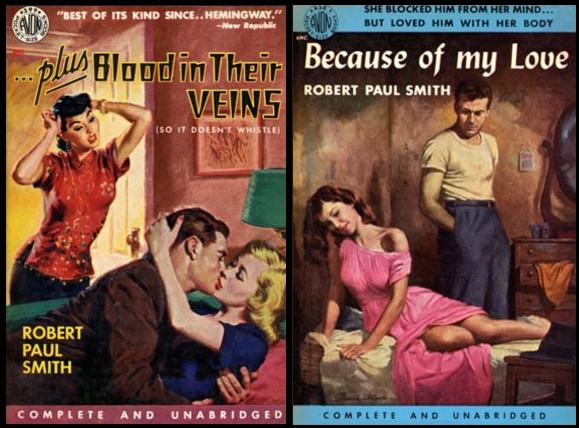

Tagged as a realistic writer in the Hemingway mode, Robert got generally good reviews and tagged with that dreaded epithet of “promising.” The novels created enough of an impression to all be reprinted in paperback by Avon in the 1950s, with wonderfully lurid covers.

Then in 1954, Robert did the one thing posterity will remember him for, if the majority of American newspapers are the judge. He co-wrote – with Max Shulman, the hugely successful writer of humorous novels and short stories, and creator of Dobie Gillis – a Broadway play. The Tender Trap ran for only 101 performances and got tepid reviews as a funny but insignificant comedy. Yet such was the draw of Shulman’s name that MGM made a movie deal three months before the play opened. The finished movie, released in 1955, starred 40-year-old Frank Sinatra and 23-year-old Debbie Reynolds who he course picks over 38-year-old Celeste Holm. The result, with an Oscar-nominated song, was a money-making hit.

The Tender Trap poster

That newspapers reporting his death in 1977 chose to remember Robert by this achievement at a remote speaks both to the status of Broadway in the 1950s and the general literary disdain that draws a line between humorous and “real” writers. Elinor’s disappearance compounds the snobbish disparagement.

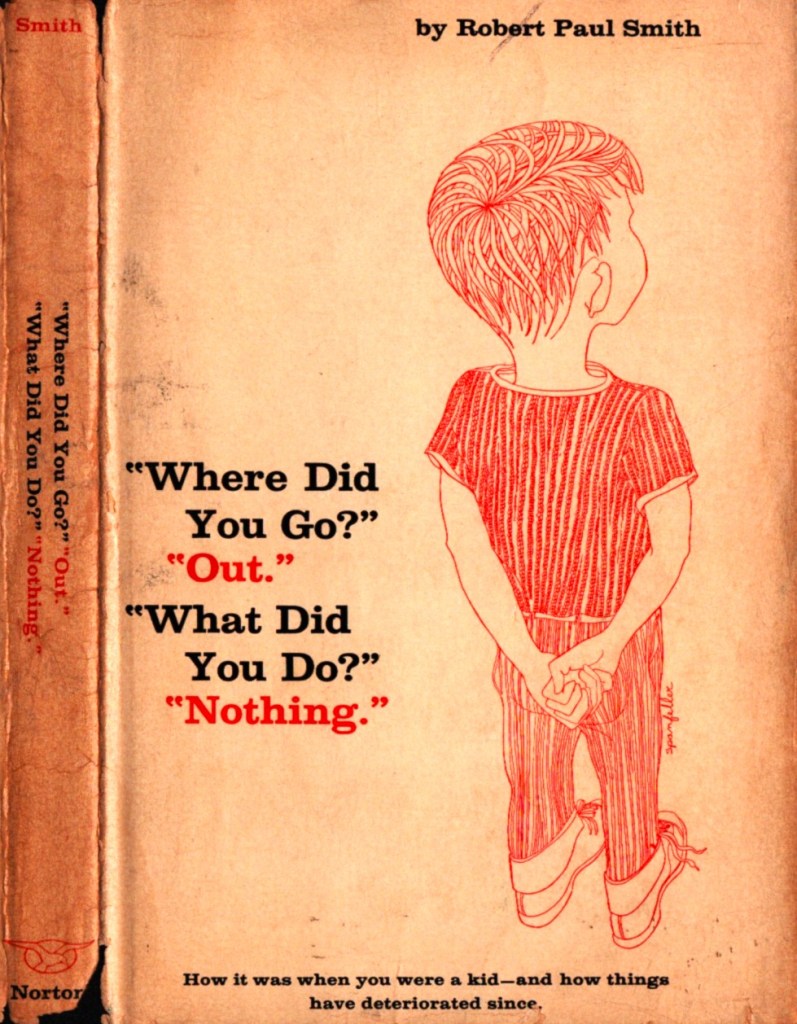

By any sane measurement of fame, Robert’s 1957 oddly titled little book that spent a year on the Times best sellers’ list, selling 170,000 copies in hardcover, would be the success that mattered. “Where Did You Go?” “Out” “What Did You Do?” “Nothing” caught the nostalgia for the past that already suffused suburban parents. Although portrayed as a lament for overscheduled and overregimented children – “there are play groups and athletic supervisors and Little Leagues and classes in advanced finger painting and child psychologists” – in a way that eerily presages similar complaints in today’s society, my take is that Robert wanted to relieve his childhood in then semi-rural Mt. Vernon more than he cared about modern kids. His was the cry of all crotchety conservatives: Things were better in the simpler past [of childhood than in the complicated modern world [of adulthood].

The world listened and roared its approval. Robert’s words – 100+ pages of intimately described details recreating the 1920s as a time of innocent fun and innocent badness (gangs for whom a knife meant a tool to play mumbly-peg and sex meant a peak at Film Fun magazine) – hit a totally unexpected nerve. Elinor’s satires were great fun, but her target – advice to young housewives – was already omnipresent. They could have been written a quarter century earlier or later and have a similar audience. Robert’s memoirs – not better than Elinor’s inventiveness, instead wholly different – arrived just as millions of Americans discovered how unsettling modern life could be. The split between the suburbia the Smiths inhabited and pre-war small-town America seemed disconcerting, overwhelming, and utterly meaningful. The more the country diverged from that past, the more the book mattered. Robert received tons of mail in response to Nothing, many of the correspondents, adults, complaining how lonely their lives were in comparison with the tight-knit gang of kids described in his book.

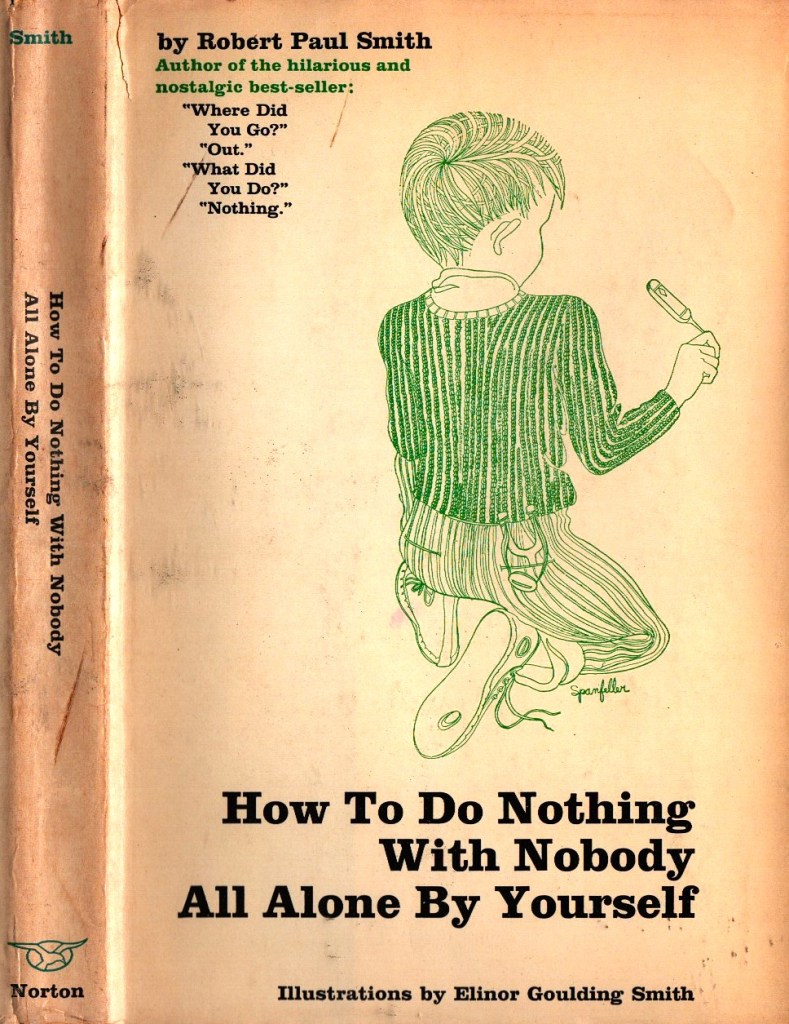

Robert couldn’t do anything for adults, but he tried to talk to kids. How to Do Nothing With Nobody All Alone By Yourself appeared in May 1958. Called by one reviewer “a sort of appendix” to Nothing, Robert lays out instructions for dozens of gadgets to be made and played with without that gang of kids. For lack of YouTube video, the pages are dotted with dozens of how-to illustrations. Wonderfully, the artist was Elinor, the only time the two would collaborate.

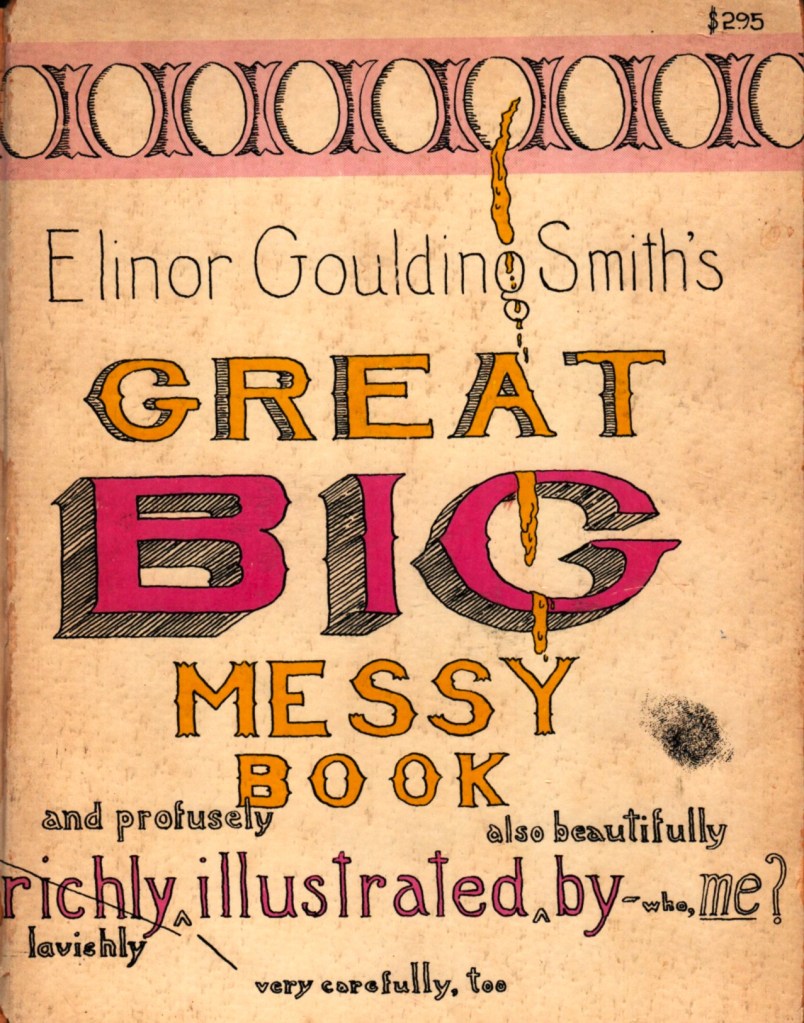

Aside 4: Elinor collaborated with herself on Great Big Messy Book (1962), illustrating her own volume of how-to-do-it activities for adults, obviously riffing off Robert’s work for kids.

And then came the June 1958 interview on Person to Person.

To recap, here’s what the Smiths did to warrant that appearance.

| Author | Title | Copyright Date | Hit Best Sellers List |

| Elinor | Housekeeping | Oct. 26, 1956 | |

| Robert | Nothing | April 16, 1957 | Aug. 8, 1957 |

| Elinor | Baby and Child Care | Sept 27, 1957 | |

| Robert | Translations | Feb. 10, 1958 | |

| Robert | Alone | May 13, 1958 | June 8, 1958 |

| Elinor | Confessions | Oct. 8, 1958 |

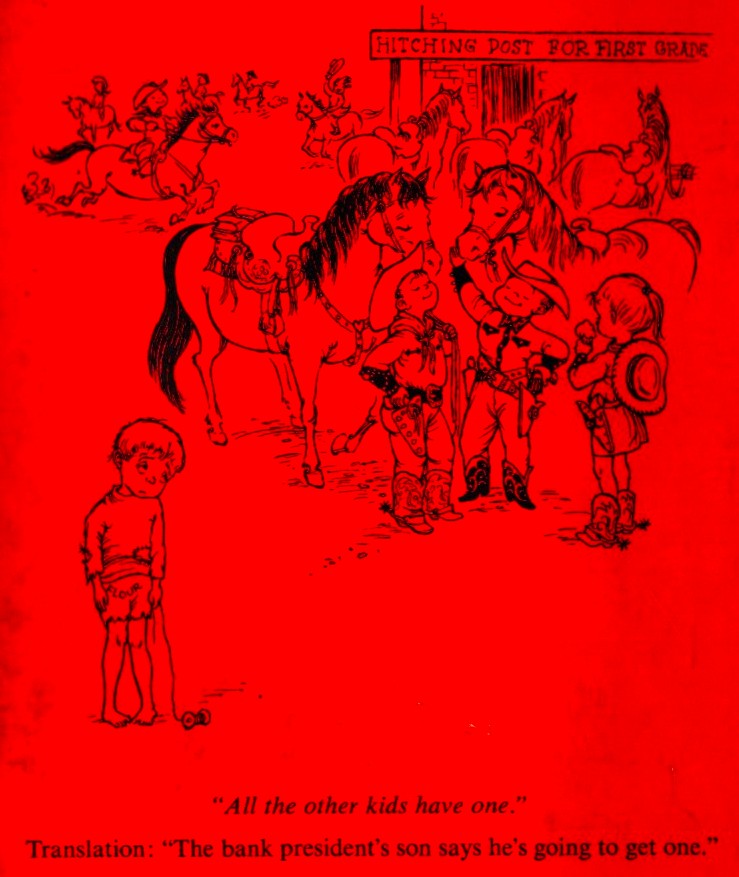

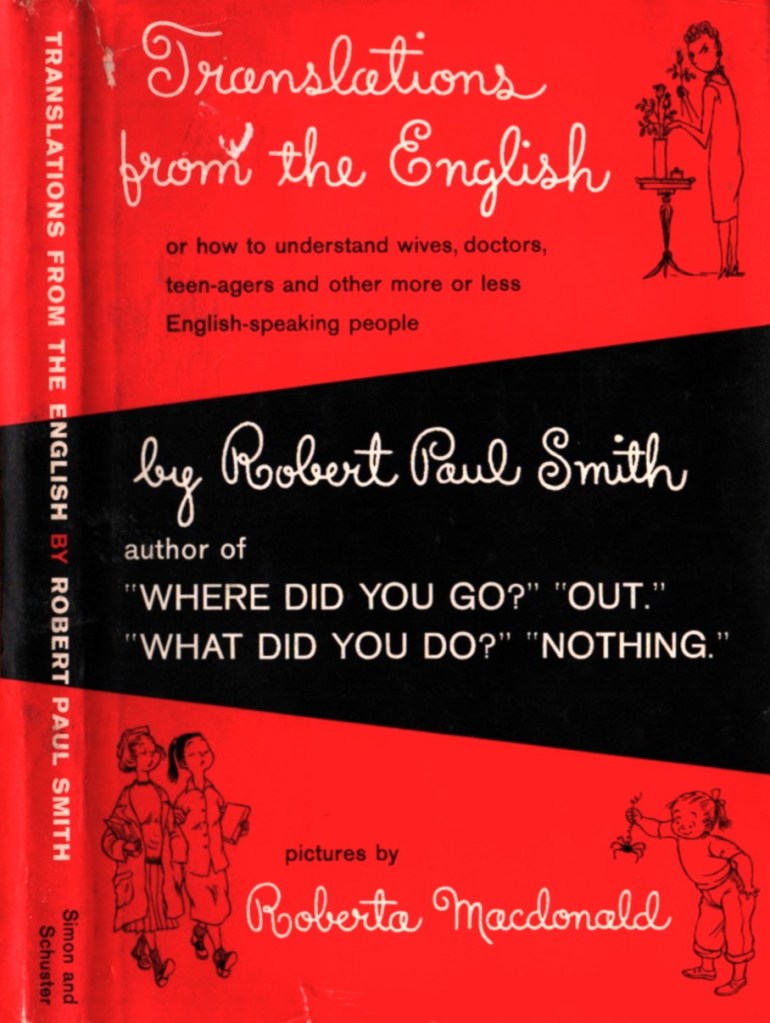

Translations? Where did that come from? Overlooked at the time, Translations from the English may have invented, or at least popularized, a style of humor, an acknowledgement that much of the short back-and-forth between people consists of artful nudges to the truth. The first chapter, on what kids say but really mean, sold the book.

“I’m all dressed” — He has his undershirt on.

“I’m all dressed except my shoes” — He does not have his undershirt on.

“I’m just tying my shoelaces” — He’s looking for his shoes.

Anyway, that’s five books – two of them hitting the Times best sellers list and two others national sensations – in two years, plus a sixth announced for the fall, all aimed at the core readership of popular literature in the 1950s. That’s spectacular anytime. The Smiths were as celebrated a couple as the Kerrs.

The Smiths

And then they weren’t. Oh, the books kept on coming through the 1960s.

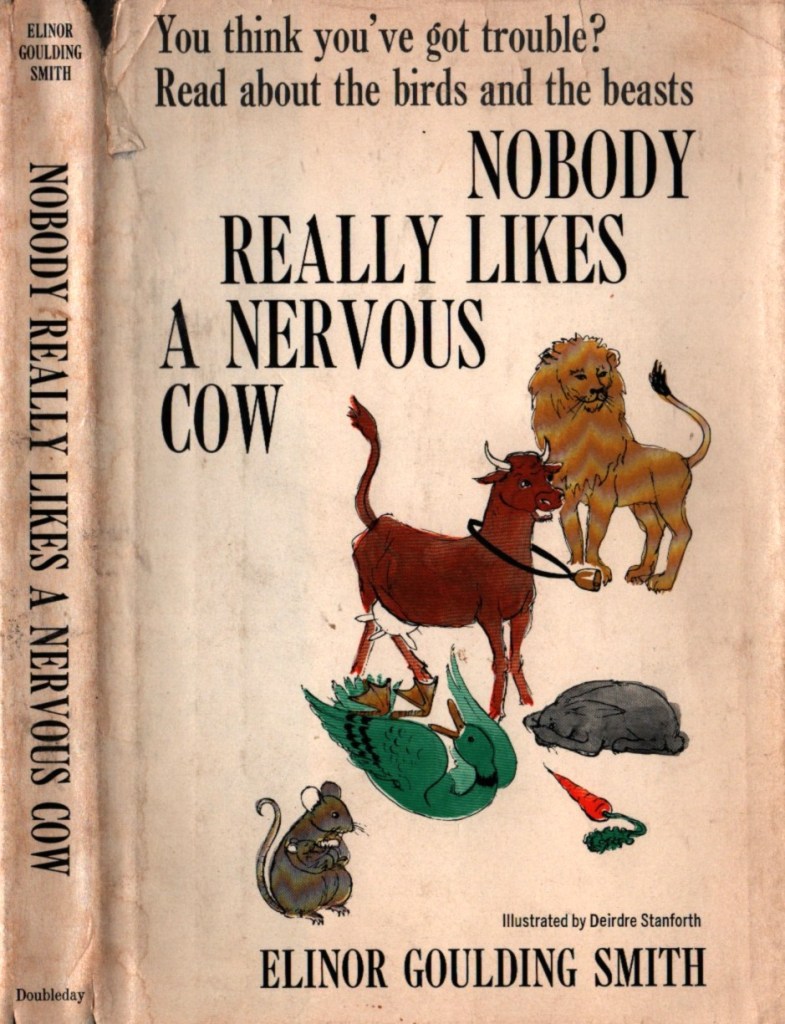

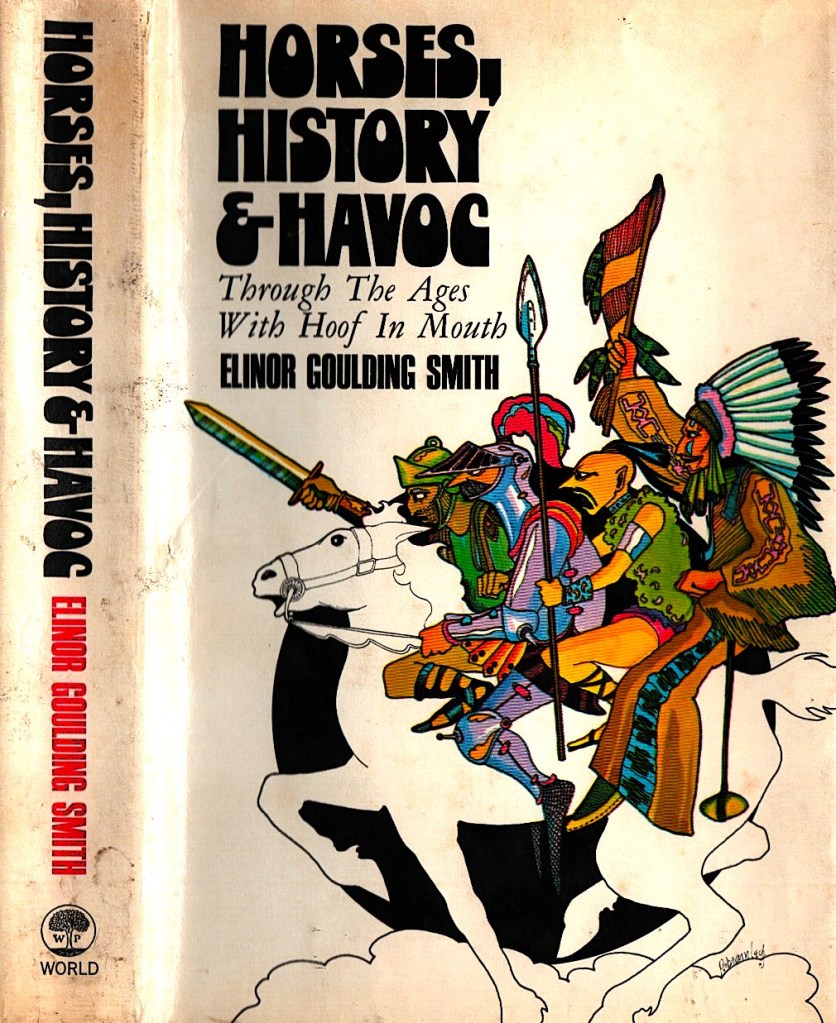

As Elinor responded to the nervous breakdown America appeared to be having in the 1950s, a trend also used for humor by new comics like Shelley Berman, Bob Newhart, and Woody Allen, she deviated wildly from her earlier persona. Nobody Really Likes a Nervous Cow, from 1965, contains a series of first-person neurotic musings from the likes of cows, starlings, and rabbits. Probably realizing that the reading public responded better to tales of people, she quickly released That’s Me! Always Making History in 1967, deeply disturbed first-person accounts of famous people from Cleopatra to William Tell’s son. Finally, Elinor did what few humorists known for essays do; write her big “real” full book, Horses, Havoc and History, a ten million year account of humans and horses replete with real research told humorously. It proved her to be the multidimensional writer that her earlier work foretold.

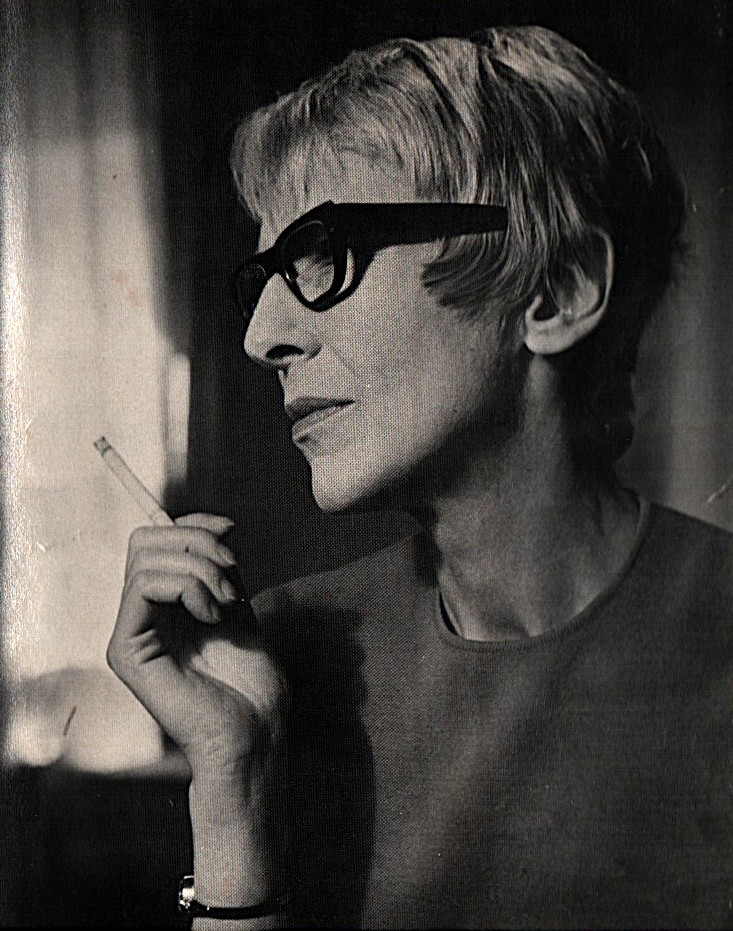

And sadly, it was her last book. Reading a foot-high stack of humor all at once can drain the appreciation of the art. Horses rekindled that love. It may be my favorite humorous look at history, even over the books I’ve included in this site by authors that I venerate. Elinor wrote with a jaundiced view of history that rivaled that of Will Cuppy, and kept to a tone of sorrow for having to report all the dreadful details. The interweaving of history and humor does not lend itself to pull quotes but an author who titles a chapter “The Dark Ages, Dammit” understands the folly of romancing the past. No wonder the author photo she used, above, presents a sterner self that the banged housewife of yore. Or maybe she was auditioning for a 50’s French noir film.

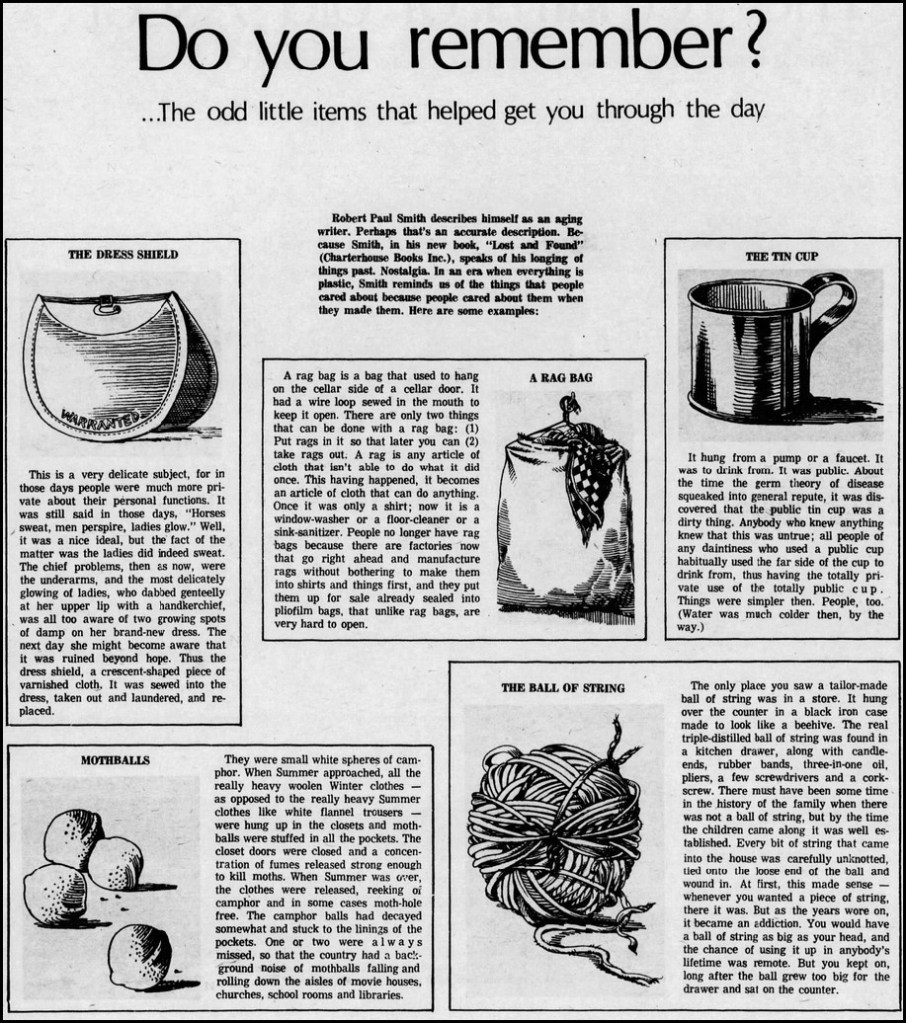

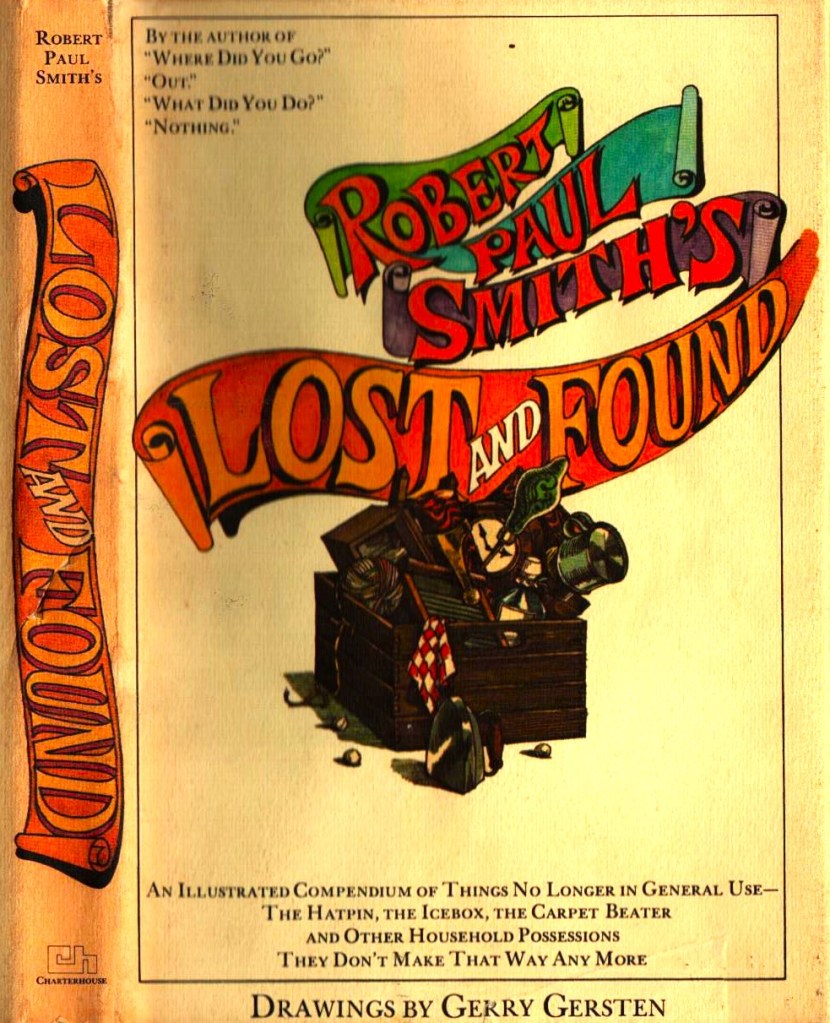

Robert had found his subject and never deviated from crankily denouncing the new world. Children and memories of his childhood remained his subject, one might say his obsession. He wrote three children’s books in the 1960s and a book of poems saw its way into the abyss that volumes of poetry inhabit. Four more books of nostalgia mixed with criticisms of the modern world appeared, the last one, Lost and Found, in 1973. Writing about the hatpin, the icebox, and the carpet beater was not in tune with the times. As one reviewer put it, the book was “suitable” for people over 50, who mostly adored it.

Under 50s, the kids who didn’t know or care about mumbly-peg in the 1950s, had grown into adults who didn’t care about nostalgia. Or, for that matter, horses. Not that the couple lacked for money. Productions of The Tender Trap appeared on stages all over the country through the 1970s. (And out of the country. I found a listing for it on Papua, New Guinea’s national radio. I also found a critic liking a production, despite it’s “creaking” and “dated” script.)

Why neither Smith continued their career past 1973 is a puzzle. Maybe royalties from the play made them independently rich. Perhaps it was their return to the horror that was 1970s Manhattan. Possibly illness also presented problems. In any case, they had little time left in which to work. Both would die within a few years, comparatively young, Elinor at 61, Robert at 62. As I said above, Robert’s death was recognized, mostly with reference to The Tender Trap, though occasionally his first book would get a mention. Elinor simply disappears from newspapers, although the Times did her courtesy of a one-line mention in Robert’s obituary. Oddly, her books read better today than his. Housewives and mothers are timeless, no matter the medium.

Bibliography of Humorous Works

Elinor Goulding Smith

- 1956 – The Complete Book of Absolutely Perfect Housekeeping (drawings by Roy Doty)

- 1957 – The Complete Book of Absolutely Perfect Baby and Child Care (drawings by Roy Doty)

- 1958 – Confessions of Mrs. Smith (drawings by Roy Doty)

- 1960 – The Battered Bride (drawings by Roy Doty)

- 1962 – Great Big Messy Book (illustrated by Elinor Goulding Smith)

- 1965 – Nobody Really Likes a Nervous Cow (illustrations by Dierdre Stanforth)

- 1967 – That’s Me! Always Making History

- 1969 – Horses, History and Havoc

Robert Paul Smith

- 1957 – “Where Did You Go? “Out” “What Did You Do? “Nothing” (illustrations by James J. Spanfeller, uncredited)

- 1958 – Translations from the English (pictures by Roberta Macdonald)

- 1958 – How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself (illustrations by Elinor Goulding Smith)

- 1961 – Crank

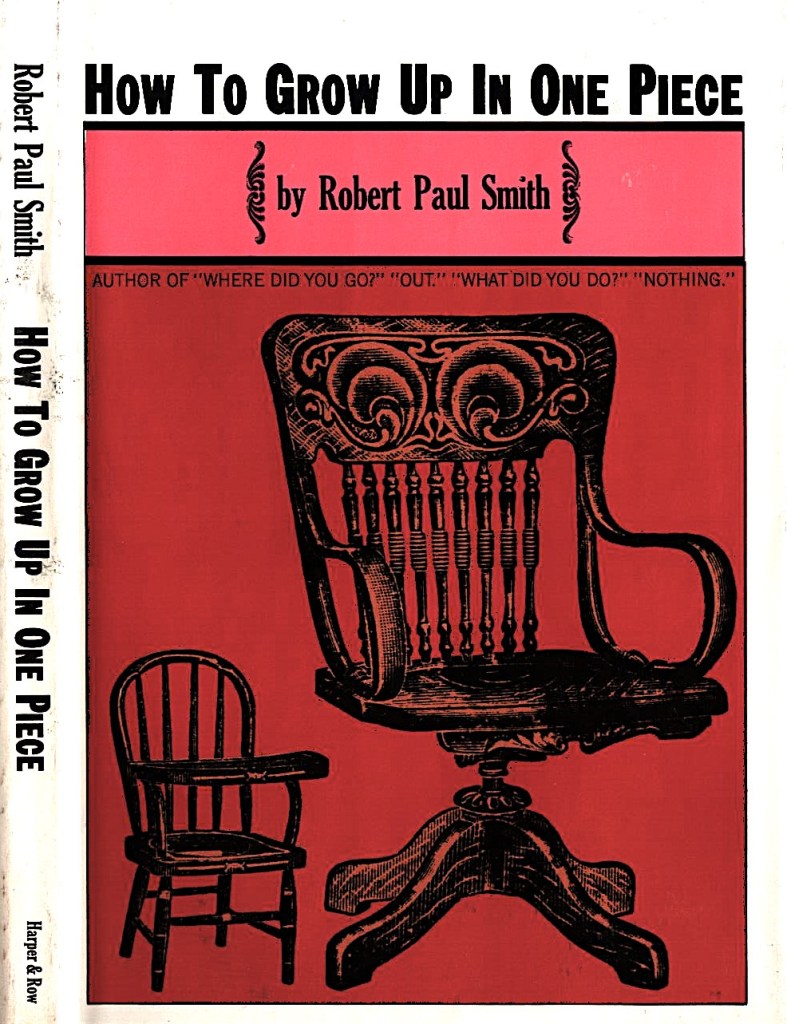

- 1963 – How to Grow Up in One Piece (design by Push Pin Studio)

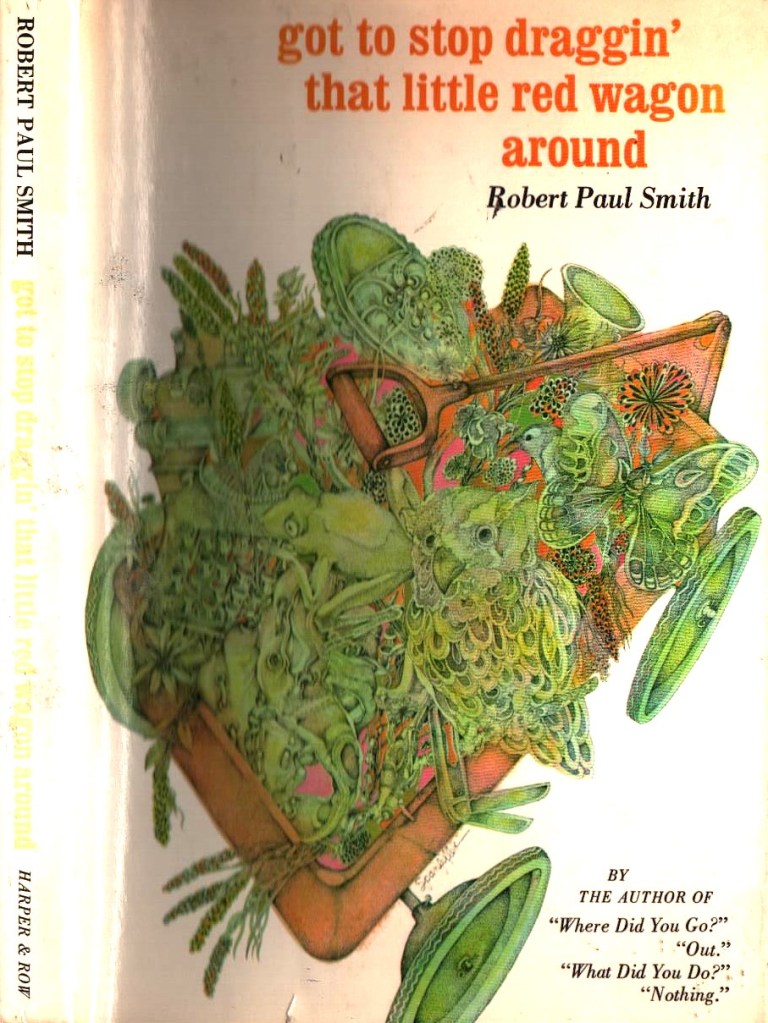

- 1969 – Got to Stop Draggin’ That Little Red Wagon Around

- 1973 – Robert Paul Smith’s Lost and Found (drawings by Gerald Gersten)

You must be logged in to post a comment.