“‘Scuse me while I kiss this guy” is probably the world’s most famous Mondegreen. Jimi Hendrix never said it – he’s more picturesquely kissing “the sky” – but the slurring of syllables in song often results in misheard lyrics. Famous examples include “Lucy in the sky with colitis” instead of “Lucy in the sky with diamonds” and “José, can you see” for the “Star-Spangled Banner’s” “Oh, say can you see.” I still insist that Bob Dylan should have written the evocative “a small, dark look on his face” instead of the flat “a small dog licking his face” in “Jokerman.”

All languages are prone to this mishap, and English has a long tradition of incorporating misheard or mispronounced terms in other languages. Cucaracha became cockroach, chaise longue became chaise lounge. This is known as the Hobson-Jobson effect, after an example of the English misunderstanding words in India. Not to be confused with a malaprop, the humorous switching of one long word for another, or an eggcorn, which puts more familiar words in older sayings, like “one foul swoop” for “one fell swoop,” or folk etymology, which is why “Welsh rabbit” is often called “Welsh rarebit.” All of these are formally subsets of what linguists and absolutely nobody else call acyrologia.

Someone had to give a name to this phenomenon in silly song lyric mistakes and that someone turned out to Sylvia Wright. Her essay “The Death of Lady Mondegreen” in the November, 1954, issue of Harper’s Magazine gave posterity a term which hasn’t died. Here’s the original opening.

“When I was a child, my mother used to read aloud to me from Percy’s Reliques. One of my favorite poems began, as I remember:”

Ye Highlands and ye Lowlands

Oh, where hae ye been?

They hae slain the Earl Amurray

And Lady Mondegreen

I won’t make you wait. The actual last line reads “And layd him on the green.”

If you are a normal American reader in the 21st century, you probably didn’t even make to the poem before your brain stumbled. Her mother read from what?

The Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (sometimes known as Reliques of Ancient Poetry or simply Percy’s Reliques) is a collection of ballads and popular songs collected by Bishop Thomas Percy and published in 1765.

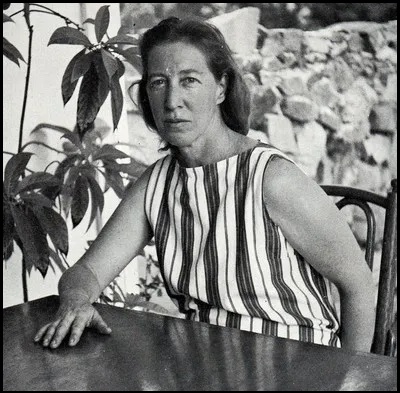

Wright was born in 1917, so Dr. Seuss wasn’t at any bookstore. Still, few households even in that day and age read a 17th century Scottish ballad about a 16th century murder to their children. (Its formal title is “The Bonnie Earl o’ Moray.” Morey is pronounced Murray.) You may infer from this fact that the Wright household was not a usual one.

Sylvia’s father, Austin, was a prominent lawyer and law professor who moved the family from firm to firm and prestigious school to prestigious school. In all these locations he had a strict routine. Every night he would remove himself to his study, close the door, and work through the evening. Little wonder that wife Margaret needed to find something to amuse her four children.

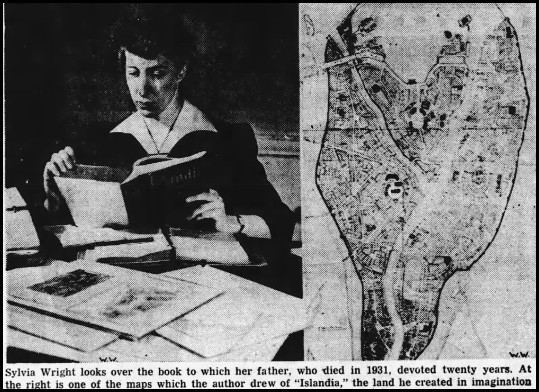

Not until his sudden death in an automobile accident in 1931 did the family learn that Austin had not been working on his law books, as they had thought. For more than two decades he had obsessively been creating a utopia far more detailed than Tolkien’s Middle Earth. His island, called with lawyerly precision Islandia, was detailed with 53 maps, its own language, religion, and customs, an 80,000 word history, a bibliography of (invented) works about the island, and a million words of a novel letting its characters act out the world. In longhand.

Over the next decade, Margaret and Sylvia typed out the 5,000 pages they found, neatly sorted into folders. They worked with Mark Saxton, an editor at Farrar & Rinehart, to Procrustes the thing into a mere 1,000 pages and published the book in 1942. Despite, or perhaps because of its size, the novel made a huge splash. The New York Times Book Review ran the review on its front page, and concluded “it is a unique, brilliantly conceived book which one reads with avid excitement despite its great length.” Islandia has not been out of print since.

Aside: Every source gives different estimates for the number of pages and/or the number of words. The number I’m giving is sourced to the April 19, 1942, Baltimore Sun, which also gives us this image of the young Sylvia.

Sylvia went to Bryn Mawr, where she won the English prize. Still in her twenties, she thereafter wrote. And wrote. And wrote. The collection her essay appeared in, Get Away From Me With Those Christmas Gifts … and other reactions, appeared in 1957, with 18 previously published essays and eight new ones. It included, for once, a helpful “About the Author” that I can crib from:

[S]he worked in publishing (Farrar & Rinehart), for the Office of War Imagination in New York and overseas, for the magazine Harper’s Bazaar, and for the OWI’s peacetime successor, the U.S. Information Service. She … has herself been published in such typical middle-twentieth-century magazines as Harper’s, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, The Reporter, and High Fidelity.

The Bazaar was her regular gig; she became an editor an had a monthly column. an editor at Harper’s Bazaar where she had a monthly column. A series of serious essays about the world appeared in The Reporter. She later put several novellas together into a collection called A Shark-Infested Rice Pudding, which is not, repeat, not humorous. (The title does come from the children’s riddle: “What is white, has raisins, and is terribly dangerous?”) Not much more information is available on her. She doesn’t have a Wikipedia page. Her name also appear in Fighting Hellcats #6, but I’m confident that’s mere coincidence. Any fame she might have comes from that one essay.

A brief New York Times obituary contributes this tantalizing tidbit about her family.

At her death, Miss Wright was writing a biography of her greataunt, Melusina Fay Peirce, an early feminist and first wife of the American physicist, mathematician and philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce.

The neologism mondegreen nevertheless appeared to fill a waiting void. Percy no doubt rang few bells in the public’s’ minds, but her other examples, like “Gladly the Cross-Eyed Bear” and “Our Father who art in heaven, Harold by Thy name,” were already legendary, Harold dating back into the 1870s. The first newspaper mention of Sylvia’s contribution to the language appeared immediately upon the release of the Harper’s issue, although true recognition waited until it was reprinted in her one and only collection of humor pieces, 1957’s Get Away from Me with Those Christmas Gifts. The volume also contained a new short story, “The Quest of Lady Mondegreen,” about her old characters and some new ones like Round John Virgin, written in response to the many letters she received on the original article. Every review had to mention mondegreens; they undoubtedly sold many copies for her.

Why Sylvia wrote no more humor is unclear. (A second Lady Mondegreen story did appear in her collection, in response to huge reader reaction to the magazine piece.) Why after such nationwide publicity the subject languished for two decades is equally murky. New York Times uber-columnist William Safire came to her rescue in a May 27, 1973, “On Language” column, reprinted in a zillion newspapers. Mondegreen became an evergreen, a sure hook for a column by columnists of all stripes. Since then, the oft obscured lyrics of rock songs have contributed mondegreens by the thousands, with the Hendrix lyric becoming the default example of the phenomenon. As early as 1998, a website kissthesky.com, still findable, started collected examples, boasting 122,515 submissions as of this writing. Gavin Edwards launched a series of misheard lyrics books by using ‘Scuse me while I kiss this guy as the title.

Today “Mondegreen” has a Wikipedia page, while Sylvia doesn’t. The injustice!

Bibliography of Humorous Works

- 1957 – Get Away From Me with Those Christmas Gifts (illustrated by Sheila Greenwald)

You must be logged in to post a comment.