- Intro

- 1876

- Max Adeler [Charles Heber Clark]

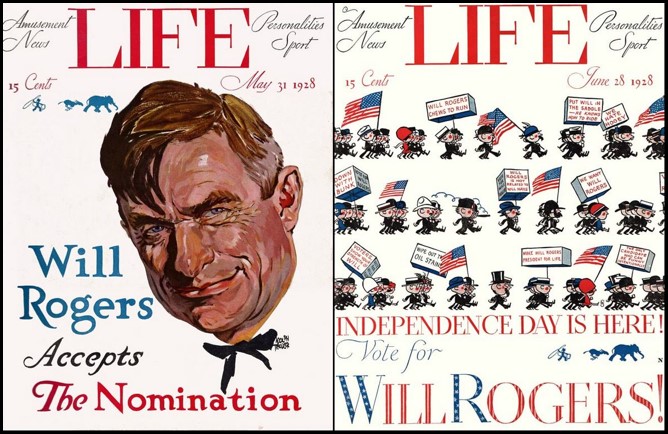

- 1928

- 1876

- Books

- 1932

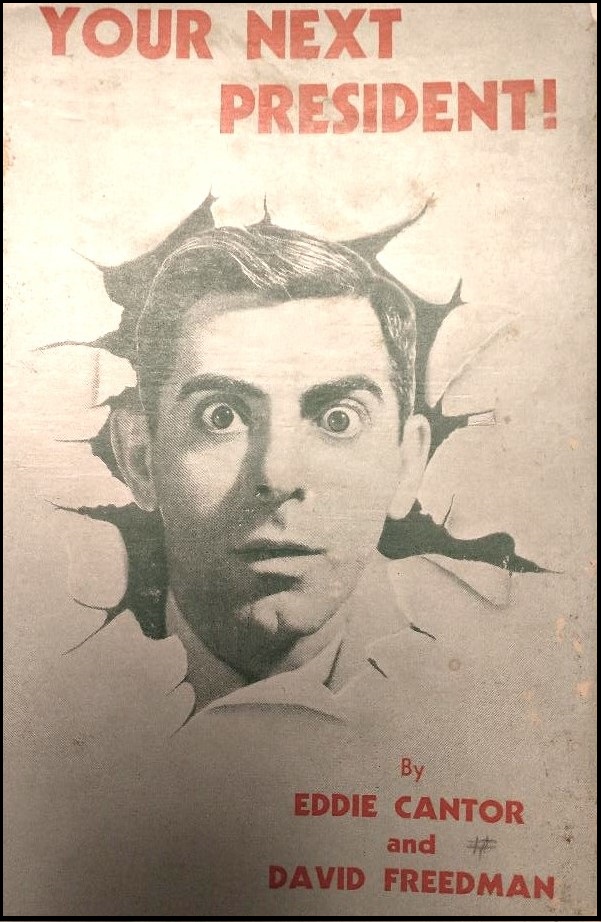

- Eddie Cantor (Your Next President!) [David Freedman – see Asides]

- 1940

- Gracie Allen (How to Become President)

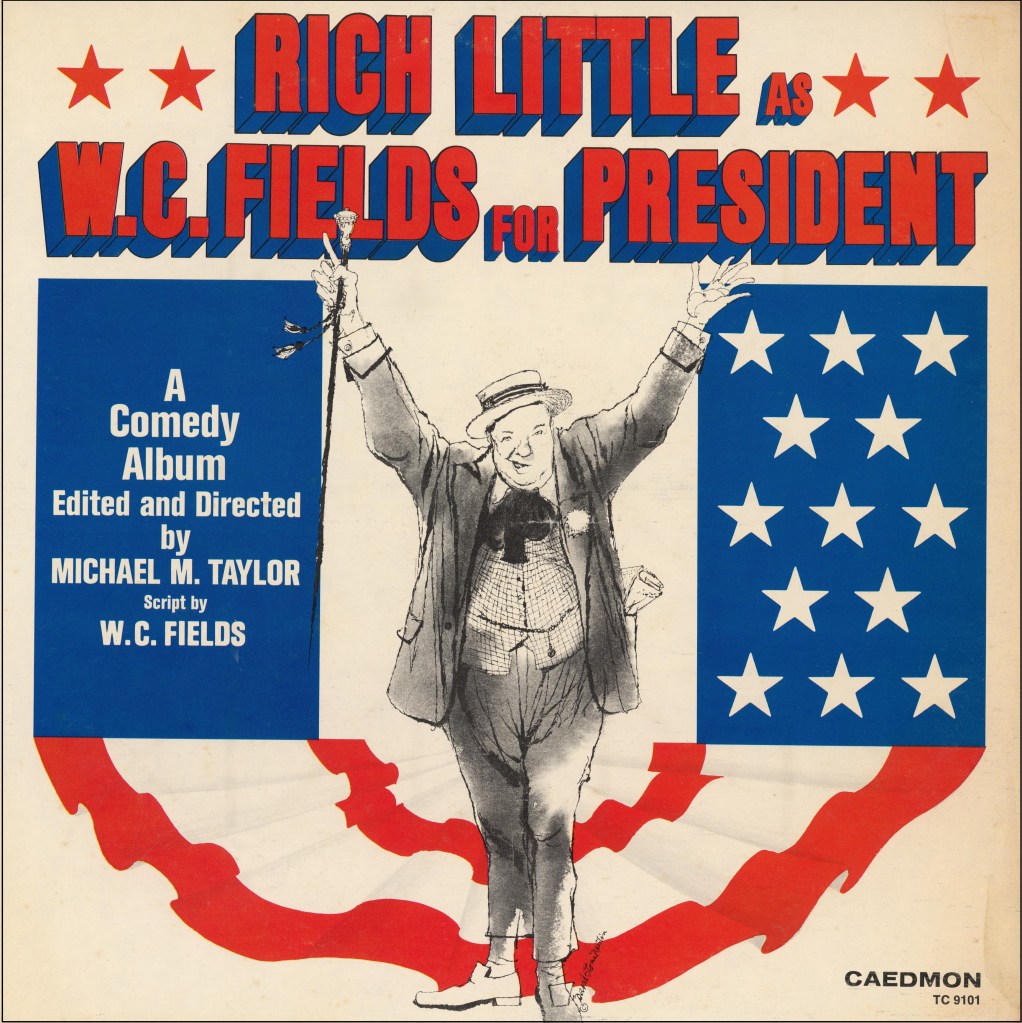

- W. C. Fields (Fields for President)

- [Charles Algernon Sunderlin – see Asides]

- 1952

- Jimmy Durante (The Candidate)

- Pogo (I Go Pogo) [Walt Kelly]

- 1964

- Jackie Mason (My Son, the Candidate)

- Yetta Bronstein [Jeanne Abel] (The President I Almost Was)

- Marvin Kitman [Kitman for President Souvenir Program – see Asides]

- 1968

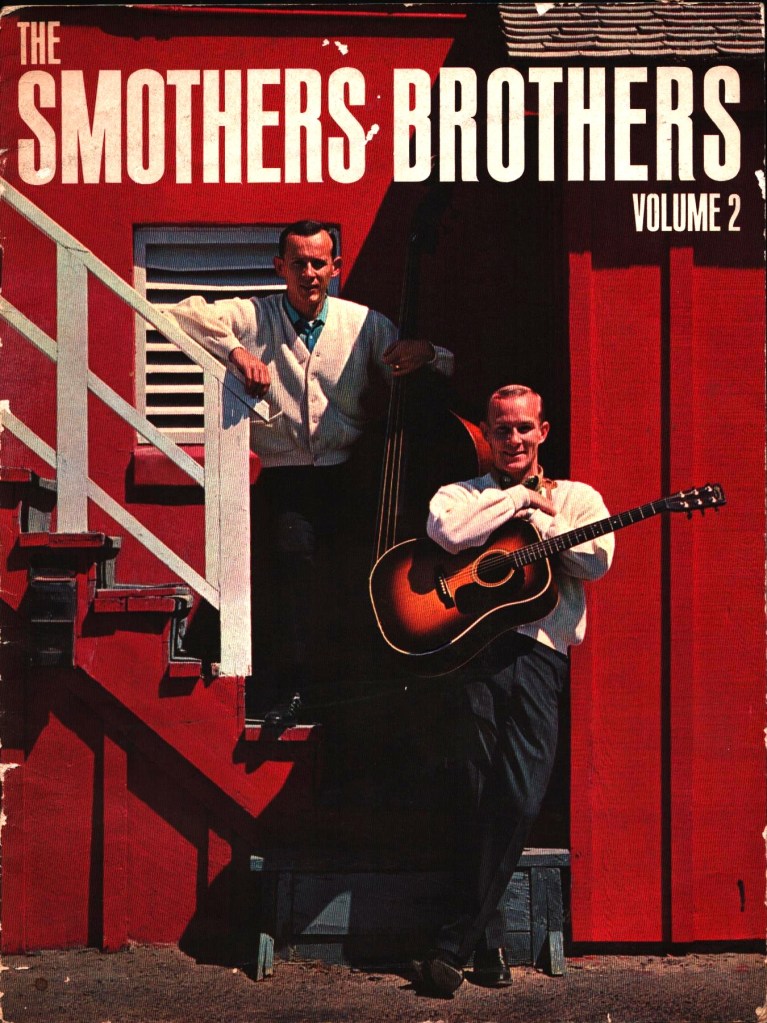

- Pat Paulsen (Pat Paulsen for President) [Mason Williams and Jinx Kragen – see Asides]

- 1972

- Pat Paulsen (How to Wage a Successful Campaign for the Presidency) (1972)

- 1932

- Asides

- Alsorans

- Al Franken (Why Not Me?, 1999)

- Stephen Colbert (I Am America [And So Can You], 2007)

- Adam Carolla (President Me, 2014)

1876

I have pretty much made up my mind to run for president. What the country wants is a candidate who can not be injured by investigation of his past history… If you know the most about a candidate, to begin with, every attempt to spring things on him will be checkmated.

Take a moment to let those lines linger in your mind, and recognize that nothing ever changes about American politics, especially the rotten bits. Journalist and humorist Charles Heber Clark, using his pseudonym Max Adeler, charged into the 1876 election in the midst of the worst corruption scandals the country had ever seen. The article, originally in the magazine Illustrated Weekly of New York and later syndicated widely in newspapers, was so good that it was later reprinted and attributed to Mark Twain and accepted as such by some down to the present.

Clark piled on the acid satire of contemporary politics. “The rumor that I buried a dead aunt under one of my grape vines is founded in fact. The vines needed fertilizing, the aunt needed to be buried, and I had dedicated her to this high purpose. Does that unfit me for the Presidency? The constitution of our country does not say so.”

That confounded constitution says only that a candidate has to be 35 or over and a natural born citizen. Everything else is left to the voter. So his forthright campaign appeal that he’s a “man who starts from the basis of total depravity, and proposes to be fiendish to the last.” has the ring of truth. Becoming President is too often about being more famous than the other guys. Politics has always been half tragedy and half farce. The farce fraction ensures that politics is always ripe for satire. And what can be more satiric than a Presidential run?

1928

Since this is a website about books, I have to hop ahead several elections. Sadly, this means I have to skip over the candidacy of Will Rogers in the 1928 election, running as head of the Bunkless Party.

(Why no bunk? Ask the dictionary, Merriam-Webster, to be specific.)

Back in 1820, Felix Walker, who represented North Carolina’s Buncombe County in the U.S. House of Representatives, was determined that his voice be heard on his constituents’ behalf, even though the matter up for debate was irrelevant to Walker’s district and he had little of substance to contribute. To the exasperation of his colleagues, Walker insisted on delivering a long and wearisome “speech for Buncombe.” His persistent—if insignificant—harangue made buncombe (later respelled bunkum) a synonym for meaningless political claptrap and came later to refer to any kind of nonsense.

Rogers partnered with Life, then the premiere humor magazine in the country, for seventeen articles. Life gave him a series of colorful covers.

The nationwide publicity in seemingly every newspaper knocked Rogers up several notches up the celebrity scale and he was soon doing his campaigning on the radio, with newspaper ads touting him as “The Only Politician Who Is Funny Intentionally.” He kept up the act until the actual election, which some of you will remember as having been won by Herbert Hoover, who was never funny intentionally.

1932

Although it may seem I did not in fact skip over Will Rogers, I could have written many pages on his wonderful campaign but limited myself to just enough to set up what I believe is the first campaign book by a comedian, a man who was the most prolific wordsmith of humor, one cranking out jokes by the thousands, someone who looked at the awesome public response to Rogers’ radio performances and wanted a piece of that action. I refer of course to David Freedman.

No, seriously. This is a website for forgotten humorists, right? Trust me. It’ll make sense in a minute.

Freedman was always a jokester, writing funny stories and sketches for Broadway revues in the 1920s, when Broadway was somehow a national phenomenon. Naturally he would cross paths with Eddie Cantor. Cantor was a superstar, moving from being a headliner in vaudeville to Broadway, where he starred in 10 years of the lavish revue The Ziegfeld Follies. (Many of those Follies paired him with the leading black comedian, Bert Williams. Both wore blackface. There’s no getting around this. Photos from that period often show Cantor in blackface, so associated with him that he would continue to be pictured in it for his books and use it into his movie career.) Freedman wrote a fat biography of Cantor, My Life Is in Your Hands, in 1928.

Though Cantor had written most of his vaudeville material for years, something had shifted. That something was the stock market. Cantor’s five millions in stock was wiped out by the crash, leaving him owing money to the bank. Freedman helped him refill his money bin. Over the next year, two humorous books on the crash appeared under both their names: Caught Short! A Saga of Wailing Wall Street and Yoo Hoo Prosperity! Freedman also ghostwrote a series of funny articles that appeared in book form under Cantor’s name as Between the Acts. Then the pair, with Morrie Ryskind, wrote a talkie, Palmy Days, released in 1931 to “one of the most epic exploitation campaigns in the history of New York City,” according to another of Cantor’s biographers.

Riding high, Cantor took over radio’s Chase and Sanborn Hour for the 1931-1932 season, getting $2500 a week and promising Freedman 10% of his radio income for life. Both deserved the money. The program was second in the ratings for the 1931-1932 season. Cantor soared from superstar to whatever the next highest level is, becoming one of the most famous people in the country, equal to, maybe above Rogers (who had contributed the Foreword to Freedman’s biography). What better gag than to also run for President? He started campaigning in the second show of the 1931 season. That needed a book as well. And who better to deliver one on command than David Freedman?

Aside 1: Freedman saw the future before his contemporaries and turned to the new media – talkies and radio – in the early 1930s. He may have been the first to understand how drastically radio would upend vaudeville. Instead of one carefully crafted and honed act that could be relied upon for years, radio would obsolete a gag as soon as it was spoken. Even professional joke writers couldn’t create a barrage of new punchlines weekly. But old jokes could be given a twist and polish. Freedman hired assistants to scour books, magazines, and newspapers, exhume the jokes buried in dead print, and file them by categories, so a skit could be quickly slapped together. Pretty soon Freedman was “writing” three (some say six) shows a week, and living spectacularly.

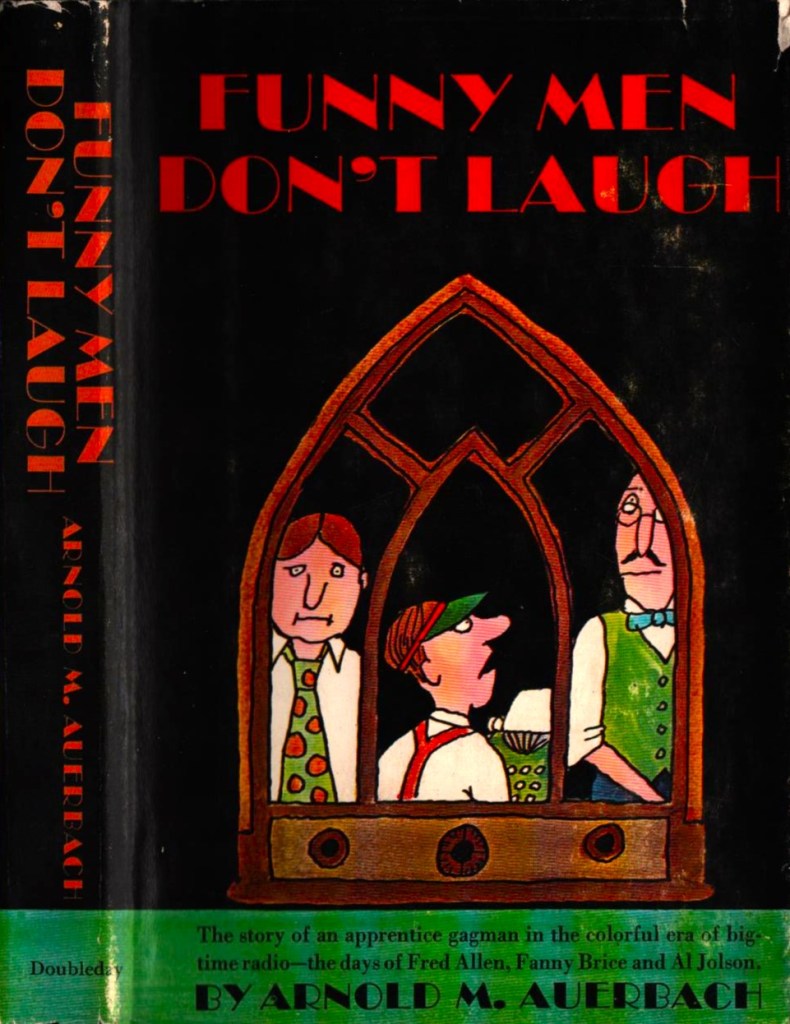

Unfortunately, he kept gambling most of it away, necessitating taking on ever higher mountains of work. Amazingly, we have a first-hand look at the incredible relationship between Eddie Cantor and David Freedman through the libelous, slanderous, and probably scrofulous memoir of Arnold M. Auerbach, Funny Men Don’t Laugh, whose first of many show business jobs was as an assistant to Freedman. Auerbach hides Freedman’s radio clients behind the names they were called: the Incompetent Paranoid, the Twitchy-Faced Dachshund, the Chicken-Headed Rodent, the Chinless Cretin, and the Slap-Happy Zany. Cantor mostly exists as a screaming voice on the phone wondering where his scripts were. Nowhere. Freedman never started them until after the last moment. Eventually Cantor canned him, causing Freedman to sue for hundreds of thousands in unpaid bills. Too movieish to believe, yet documented fact, Freedman, at 38, a stress-laden smoker and overeater, died of a heart attack the day he started his testimony in court. The suit was quietly dropped. And Freedman was forgotten even more quickly than Cantor.

Your Next President!, which cost $1.00 in Depression money, ran only 52 pages of large type, ten of then full-page pictures or blank.

Well, I’ve accepted my nomination for President, and I’m ready for the campaign. I have a slogan and a platform. Now all I need is a party – and they’re giving me one at my uncle’s house.

What follows includes some gentle mocking of contemporary politicians, a Constitutional amendment to ban pies, and a proposal for government ownership of children, skits that probably worked better on the radio spoken in Cantor’s irrepressible chirp. Reviews were brutal.

The publishers say in their blurb, “Read this book and you’ll laugh yourself out of depression.” If you read this book (which you won’t beyond the first two pages) you’ll welcome depression. Ghastly stuff. – Pittsburgh Press, March 19, 1932

Radio audiences paid no attention to reviewers. Cantor’s nonsense was exactly what the depressed audience sought and firmly embraced. His show went to number one in the ratings for the next two seasons, with ratings that were miles ahead of the second place programs, hitting numbers no one else in radio ever achieved. The seed was firmly planted.

1940

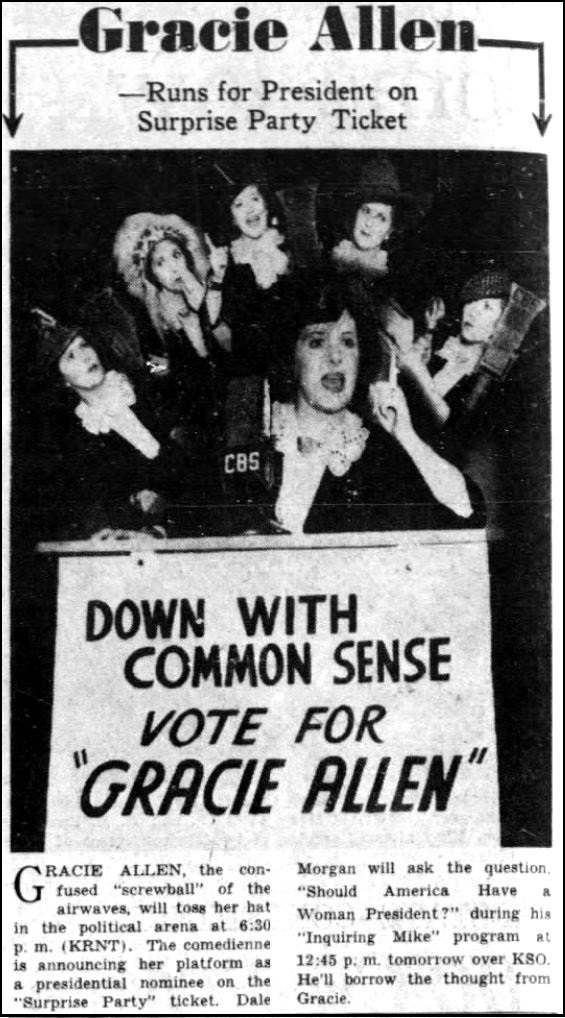

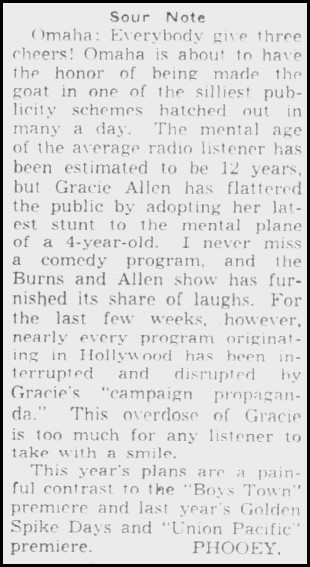

Gracie Allen for President? The “and Allen” of Burns and Allen? You might think that a dozen male egos would have crowded into the field to have their names splashed across the country, with Edgar Bergen, Jack Benny, Bob Hope, and Bing Crosby all heading shows that regularly beat The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show in the ratings. Hanging on by its fingertips, the program ran Wednesdays at 7:30 pm Eastern, 6:30 Central, a ratings death spot. And it was sponsored by Hinds Honey & Almond Cream, of Portland, Maine, a facial cleanser that I’m sure you’ve never heard of any more than me, rather than the powerful elite like Chase & Sanborn, Jell-O, Pepsodent, and Kraft, the respective sponsors of the big four.

Not to worry. George Burns had a plan. Burns, Gracie’s husband, partner in ten years of vaudeville followed by eight years in radio, creator of her character, writer of her jokes, and magnificent straight man, always turned to Gracie to power the act. The Gracie persona became a national treasure, as distinct and instantly identifiable as Fannie Brice’s during vaudeville and Lucille Ball’s in television. S. S. Van Dine, creator of Philo Vance, once the most popular fictional detective in America, dedicated an entire novel to a pairing of Allen and Vance, The Gracie Allen Murder Case. A movie was rushed out the next year, 1939, with Allen getting top billing over Vance’s portrayer, William Warren.

So in 1940… Burns was stumped. He met with his writers every week to create the next show’s script and the premise was always “Gracie does something crazy.” Their best idea was “Gracie learns opera,” as announced in a January newspaper. That didn’t last long. In I Love Her, That’s Why, a forgotten biography from 1955, George claimed a writer complained, “She’s done everything but run for President of the United States.” After giving the writer a raise, George incorporated the gag into the program, scheduled to occupy space for two shows. Gracie did Gracie-isms, like dodging the third term controversy by proclaiming that she would do her third term first to get it out of the way. And she would run as the Surprise Party.

Joke presidential campaigns work best when the actual race is at its most unpredictable or fraught. In 1932, the question in the air was whether the country could be saved from the Depression. Times were far better in 1940, so the question this time concerned whether Franklin D. Roosevelt should run for a third term. Sentiment was definitely against it. No President had ever served three terms; for many people Washington’s walking away from the Presidency after two terms settled the matter. Roosevelt, ever the canny pol, told absolutely no one what his intentions were. He didn’t confirm that he was running again until the nominating convention in July; you could get away with that in those days. The Republican nominee wasn’t known until their convention in late June. Therefore, anyone could play around in early 1940.

Gracie being Gracie, she caught an unbelievable lucky break. I’ll let George describe it, from Gracie, A Love Story.

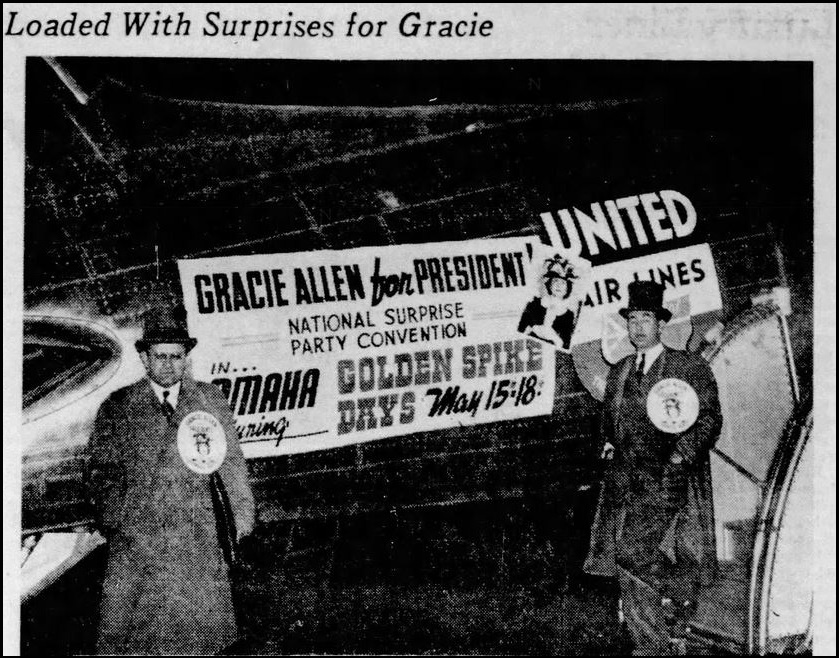

To promote the release of the movie Union Pacific [in 1939], the railroad [the Union Pacific] and the city [Omaha] had staged an Old West festival called Golden Spike Days, during which the men of Omaha grew beards and everyone wore traditional costumes. Golden Spike Days had been such a successful tourist attraction that Omaha had decided to repeat it. The Union Pacific Railroad offered to provide a campaign train for Gracie for a whistle-stop tour, and Omaha volunteered to host her nominating convention.

You can’t buy publicity like this. The train stopped in 34 cities and towns on the way to Omaha, and Gracie gave speeches to more than quarter million people. Fifteen thousand were waiting for her in Omaha and they squeezed 8,000 into an auditorium to nominate her with cheers, presumably with only one dissenter.

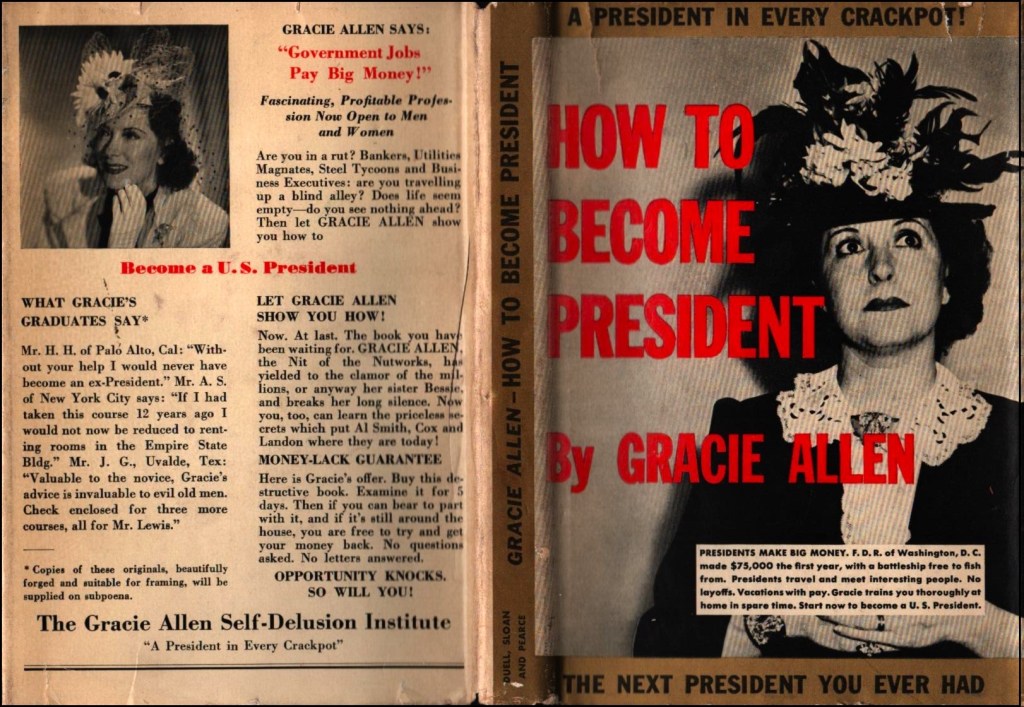

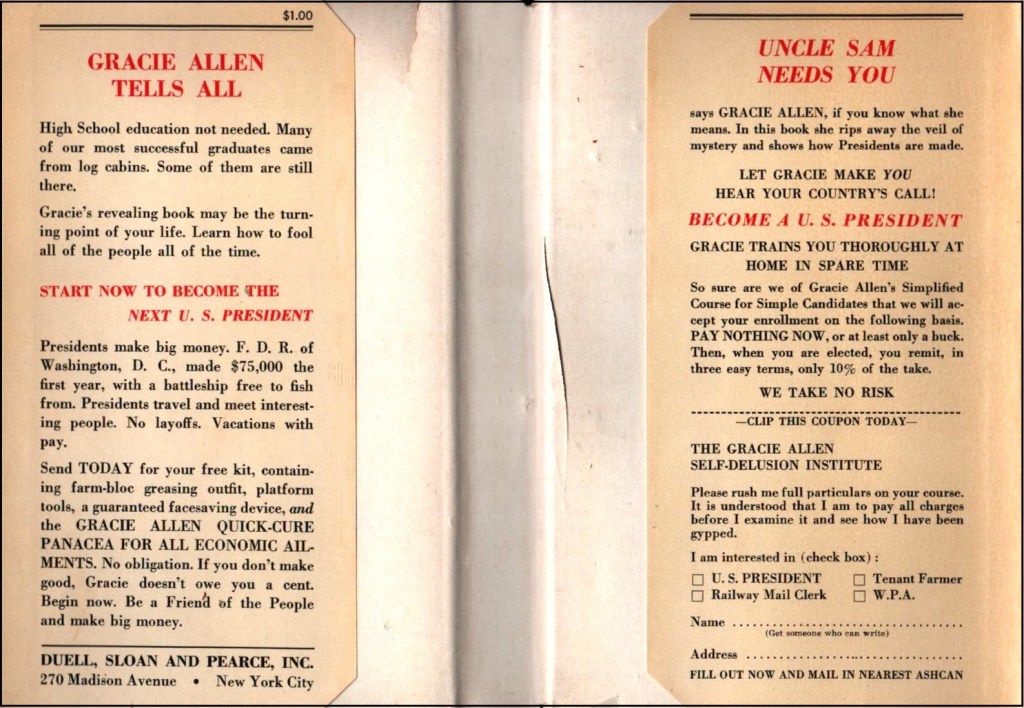

Oh yeah, there was a book, too, How to Become President, issued by the Gracie Allen Self-Delusion Center, illustrations by Charles Lofgren. Author to this day unknown, as well he should be. At 96 pages, 22 blank or with full-page drawings, it barely had more material than Cantor’s and was probably ground out in even less time. Gracie’s humor rested almost entirely on her screwball, scatterbrained, or dizzy answers to George’s questions. The book removed George and left the answers, a poor imitation of what made Gracie irresistibly endearing. It remains one of the few humor books in which the dust jacket is far funnier than the interior.

But here’s a few choice sentences nonetheless.

George Burns – that’s Mister Allen – was saying the other day that to be President of the United States you also have to have brains, integrity, ability and intelligence, but I think he was just trying to talk me into it.

You remember me. I’m Gracie Allen. I’m the candidate who forgot to take off her hat before she threw it into the ring.

Prosperity … is when business is good enough so you can buy things on credit you can’t afford to so you can save enough money to pay cash for new things after they’ve taken back the things you got on credit.

With this incredible, two-months long barrage of national publicity – plus a book – the Burns and Allen Show must have been propelled right to the top, just like Cantor’s was, right? Nope. The show tanked in the ratings and lost its sponsor. The public adored Gracie, but not her radio role as a youthful flirt who often dated other men. Gracie cheating on George? The middle-aged pair – for reasons no one later could quite explain – kept pretending on air that they weren’t married. Once this was rectified and a new sitcomish format assigned to reflect the couple’s long-standing happy marriage and two California-perfect children, they moved to a long decade as a surefire hit on radio and television. Obvious, right? But Jack Benny and Mary Livingstone never appeared as married characters and neither did Fred Allen and Portland Hoffa and their shows outdrew Burns and Allen regularly. Logic does not apply to show business.

The middle-aged pair? George refused to divulge Gracie’s age while she was alive, allowing her, as with so many other actresses, to maintain an eternal youth. Burns – Nathan Birnbaum – was born on January 20, 1896. Obituaries when Gracie died in 1964 gave her age as 58, or a decade younger than her husband, presumably having been born in 1906. But her crypt read 1902. And she graduated high school in 1914. Diligent modern research puts her birth on July 26, 1895, making her only three years younger than Eddie Cantor and a full six months older than George. Good thing, too. If she had been born in 1906 she would have been too young to run for President in 1940.

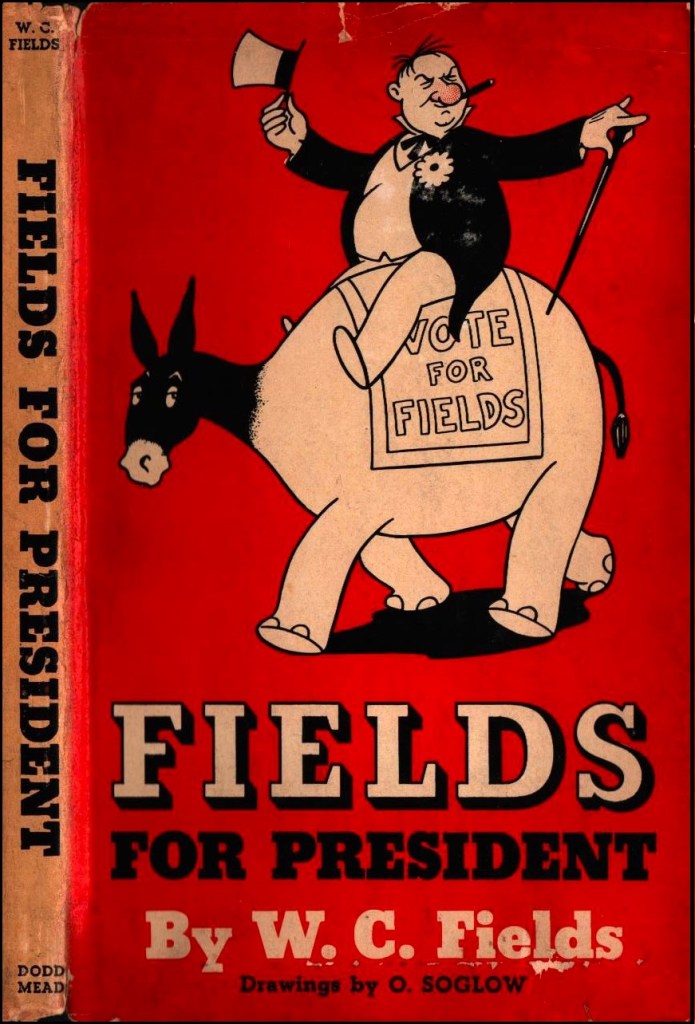

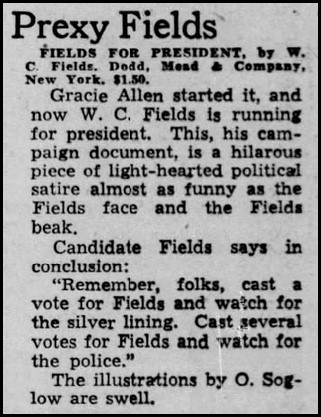

We can’t leave 1940 without reporting on the other famous comedian throwing a hat into the ring for President. In the already established tradition of oddness, this one featured a book but no campaign at all. In fact, the book barely mentioned the Presidency. And the candidate was only slightly less likely a figure than Gracie Allen. I present to you W. C. Fields for President.

William Claude Dukenfield was fifteen years older than Gracie, with a comedic persona that hadn’t varied in a quarter century. His vaudeville fame got him a role in the top Broadway show of the early century, the Ziegfeld Follies, in 1915, two years before Eddie Cantor (and Will Rogers). He followed Cantor into movies, with one big difference: he wrote his own. Cantor could throw his effervescence into any role. Fields was always Fields.

That had some pluses and minuses. Fields was unthinkable in radio as the genial host, making platitudinous introductions of guest stars, and being the butt of the jokes. He had to be the cantankerous curmudgeon, issuing insults that no one else could get away with. He found the perfect foil in the most unlikely place: the arm of Edgar Bergen controlling the mouth of Charlie McCarthy. A ventriloquist on radio? People found the idea absurd from the beginning but his show regularly topped the ratings. Charlie was supposedly a “boy” yet he always sported a top hat and tails, a monocle, and a constant leer aimed at any pretty woman in the vicinity. His being a puppet allowed him to say outrageous things that no human of the day would be allowed to. (Mae West in fact would be essentially banned from radio because of some mere innuendo on the program.) Fields’ persona was practically a cartoon itself, though. He and Charlie could trade insults (written by Bill Mack) along with ad libs the two wits always threw in. Their battles became legendary and perhaps influenced modern day roasts. Fortuitously, they solidified Fields’ persona and bolstered his fame when his movies faltered. Indeed, they led to a contract with Universal that provided Fields with some of his best-remembered films.

Doing what good editors do, Charles Rice, the editor of the Los Angeles Times’ Sunday magazine, This Week, saw that Fields, a writer, could be the source of funny articles. The pair clicked. “My Rules of Etiquette” appeared in December 1938. More followed. Rice certainly edited the submissions and may have worked as a co-writer, even writer, of some. “Make the changes you deem necessary,” Fields wrote.

Rice came up with the idea that the pieces should be collected in a book that, because it would be published in 1940, should be connected to a run for President. That the previously published articles had nothing whatsoever to do with politics or a campaign didn’t faze him. I suspect that Rice wrote the one piece in the book that did, “Let’s Look at the Record.” It certainly doesn’t sound like Fields. A feature common to all three by Cantor, Allen, and Fields was that contemporary audiences would be able to hear the words in their heads, so familiar were they with the intonations, stresses, and dramatic pauses of the actors. Fields’ book sounded more like him than the others, not surprisingly, but not in this important chapter. Here’s the attempt at a humorous platform.

- Political baby kissing must come to an end – unless the size and age of the babies can be materially increased.

2. Sentiment or no sentiment, Dolly Madison’s wash must be removed from the East Room.

3. What actually did become of that folding umbrella I left in the Congressional Library three summers ago?

The book appeared in late May 1940, mere weeks before Gracie’s book did. Reviews were short but mostly positive.

Fields, typically contrary, refused to campaign for his book, apparently avoiding even the fluffiest interviews. The book sank like a rock, forgotten. Until the 1970s revival of the early sound era greats, the Marx Brothers, Mae West, and, of course Fields. The book was reprinted in an edition with several dozen movie stills, far outdoing the text. And at a special fillip, the needed voice behind the words was provided by impressionist Rich Little, who read the entire volume on a record.

What people do remember about Fields is his signature line, “Never give a sucker an even break, you can’t cheat an honest man, and never smarten up a chump,” delivered by him in his 1939 movie called, not by coincidence, You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man. The first clause goes way back: Fields said it in the 1923 Broadway musical Poppy. Fields’ starring film career goes out on that high note. Shortly after the failure of his book, Fields’ gave a middle finger to the entire film industry. He turned in to Universal an “original story by Otis Criblecoblis” to be titled The Great Man, the term his housekeeper called him. After several months of haggling with Fields, the studio finally released something vaguely related to the “original story” and titled it Never Give a Sucker an Even Break. Marquees will boil it down to “Fields – Sucker,” he complained. Instead, the studio did him an unintended favor. Modern audiences inevitably read that title in Fields’ voice, creating an immortal of humor.

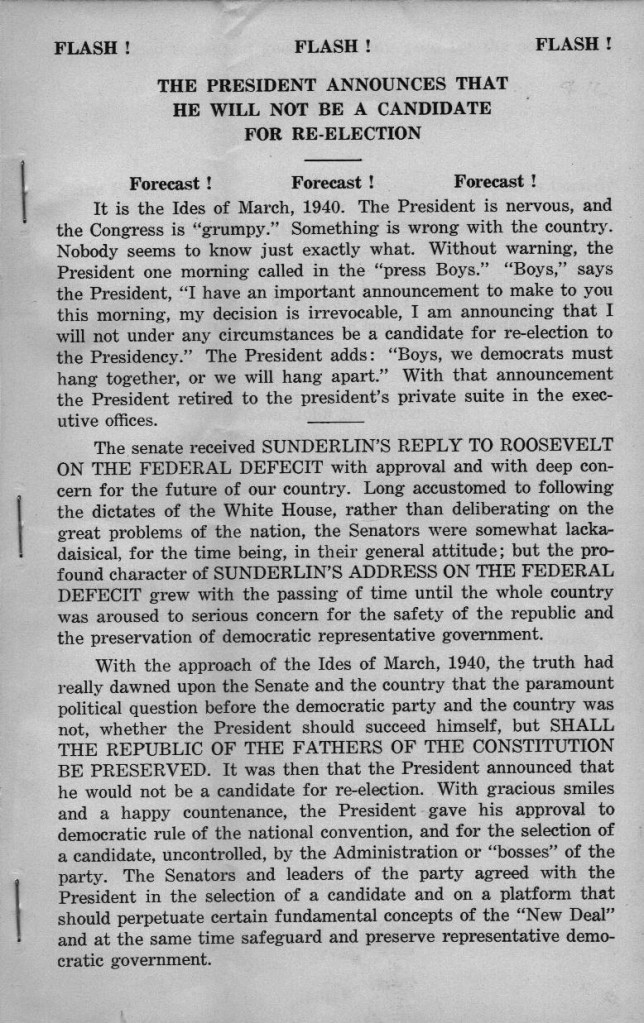

Aside 2: Some items in my collection are inexplicable. They appeared one day from where I know not. Yet they somehow appealed too greatly to toss aside.

How else can I explain the untitled half-a-sheet-of-paper-sized stapled set of nine numbered pages with the heading “FLASH! THE PRESIDENT ANNOUNCES THAT HE WILL NOT BE A CANDIDATE FOR RE-ELECTION”? The President is Franklin Roosevelt, announcing on the Ides of March 1940 that he not will run for a third term, necessitating a contested convention. You will not be astonished to learn that, after a long satiric speech by then Vice President John Nance Garner to the assembled Senate, the writer of this little playlet is named by acclamation to be be the Democrat’s 1940 candidate for President.

The author was Charles Algernon Sunderlin, a lawyer and expert on insurance law who lectured on the subject at the University of Southern California. Not much else is known about him, although he outs himself as “no supporter of the Administration” in Nance’s speech. He was against the federal deficit, supported the gold standard, and would later be shown as hating Truman’s Secretary of State Dean Acheson, which gives a good idea why he would run as a Democrat only to deride them.

The playlet is copyright 1939, yet someone stamped it OCT 1940, with an indexing number. That smacks of a library identification yet a library doing that without other identifying information would be, to say the least, odd. WorldCat finds only a handful of physical copies of this oddity extant among the libraries of the country, making this by far the rarest object in my collection.

1952

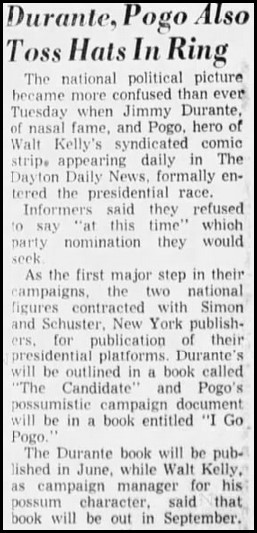

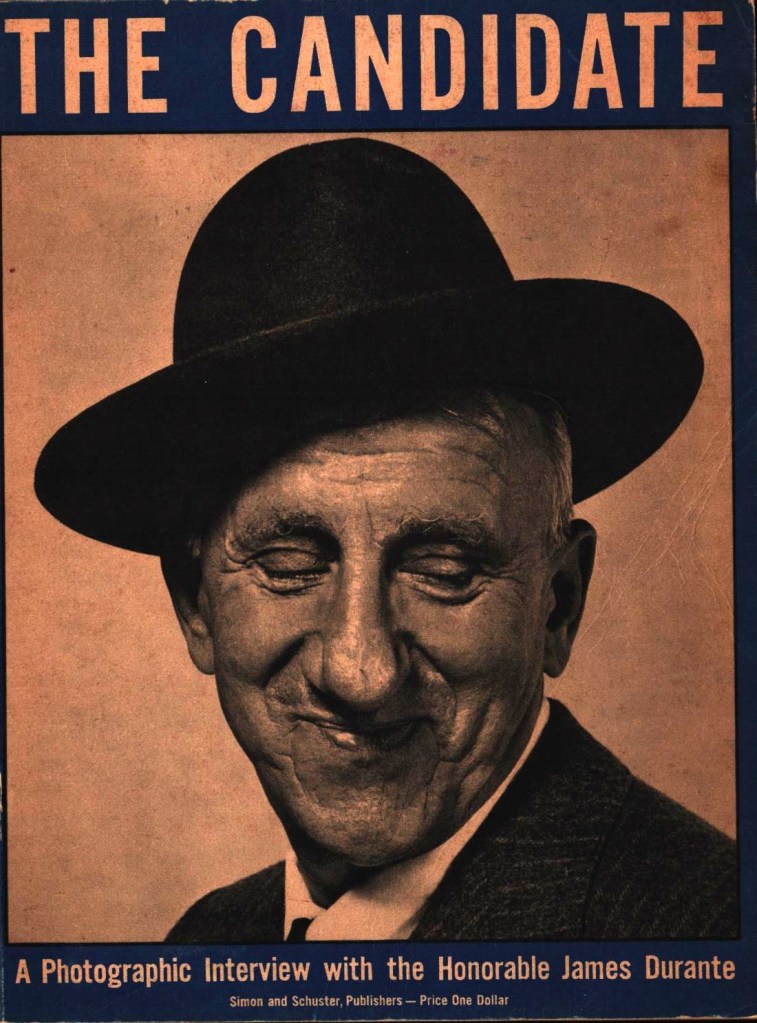

If you think it would not be possible to put out a campaign book with less original content than Fields’, you don’t understand the world of publishers. 1952 was another of those years in which candidates, particularly Dwight Eisenhower, were playing coy about running. With no candidates anointed before the summer conventions, the field was open for publicity stunts. Publisher Simon & Schuster perhaps understood this better than anyone else at the time. They choose the two humorous candidates with the widest appeal for President. Jimmy Durante and Pogo Possum.

Here in 2024 as I type these words, few people can remember how insanely popular Jimmy Durante was in 1952 and for a couple of decades previous. He was as stupendously popular as, well, as Eddie Cantor and Gracie Allen and L’il Abner, and much more more so than Pogo, who remained a cult favorite. W. C. Fields was in the pantheon as well, and he might be a smidgen more recognizable today, though not what he was even fifty years ago.

Durante rose to fame in vaudeville as part of a trio called Clayton, Jackson and Durante and they stayed friends until death. During Prohibition, their act – part-singing, part-dancing, part-witty banter – wowed customers at a series of speakeasies included the famed Club Durant, so named because the painter forget to put the “e” at the end of Durante’s name and wanted to charge extra to add it on.

After replacing Eddie Cantor as host of his radio show, Durante triangulated between radio, Broadway, and Hollywood, never quite becoming a superstar. His brand of enormous energy and talent, verbal flaws of malapropisms, self-deprecation, and a thick New York accent, topped off with a nose the size of a zeppelin that could be parlayed into endless jokes in any show in any medium, gave him both tremendous charisma and widespread public acceptance. Early television depended heavily on variety shows, usually with a rotating series of hosts, all vaudeville and radio stars. Starting in 1950, Durante was one of the hosts of NBC’s Four Star Revue, renamed All Star Revue for season 2, which ran from 1951-1952.

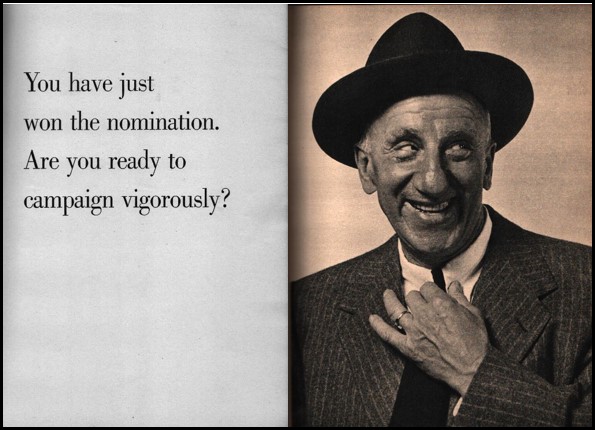

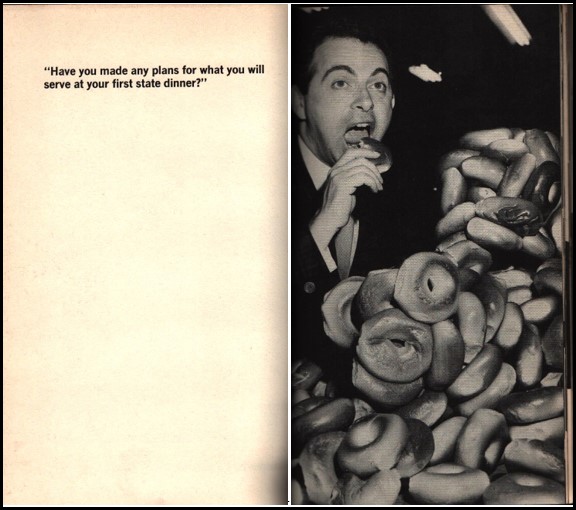

Durante’s irregular schedule gave him the spring and summer off, perfect timing for him to publicize his book. Simon & Schuster released The Candidate: A Photographic Interview with the Honorable James Durante in late May.

The wordage in The Candidate sets a new low. A question in large type on one page is followed a page later by a picture of Durante mugging an answer.

A squadron of people were necessary to fill the 118 pages. Famed photographer Philippe Halsman took most of the pictures, with the add of Schulyer Crail, Yvonne Halsman, and Ylla. Halsman is credited with the one above. A “Publisher’s Note” revealed that Durante’s songwriter Jackie Barnett “suggested a number of excellent captions [meaning the questions].” Charles Lederer, another Fowler drinking buddy, “gratuitously suggested captions, which were, unfortunately, so much better than the publisher’s original ones that they had to be incorporated.” Another humorist, Roger Price, “wandered around in time to supply some fine suggestions.” Sounds like the writers’ room on a late-night talk show.

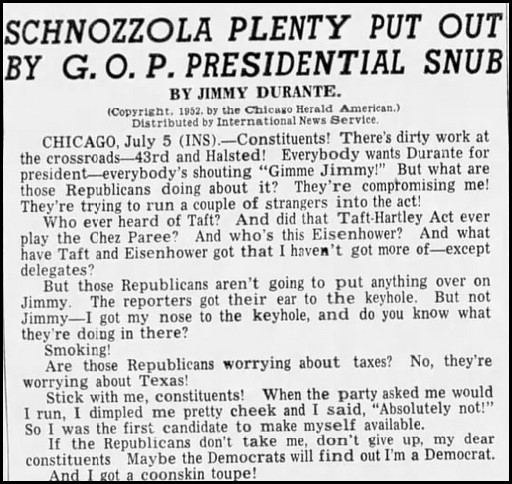

If Durante’s name and picture weren’t enough to sell an inexpensive oversized paperback, Durante doubled down by doing double duty. He cunningly showed up to do a week of his act in Chicago during the Republican convention, then filled with delegates torn between Eisenhower and Senator Robert A. Taft. To mark his visit – and promote his book – a daily piece under his name, undoubtedly written by a press agent or someone similar and datelined from the convention, was syndicated across the country.

In 1951, Gene Fowler, journalist, author, and drinking buddy of W. C. Fields, put out a biography, Schnozzola, a play on the Italian word for nose that Durante himself used as a nickname, alternating it with the Yiddish-derived Schnozz or Schnoz. That helps explains the headline above and this one on this account of Durante’s reception in Chicago.

Publicity of The Candidate fell off after the Republican convention, probably since Durante didn’t stay around for the Democrats, but Durante couldn’t help mentioning the “campaign” on television. Margaret Truman, President Truman’s daughter, returned to the All Star Revue in October for another musical number. They plugged the book and also sang a “specialty” song called, naturally, “The Candidate,” written, also naturally, by Durante and Jackie Barnett. She wore a button, too: I Like Durante, a play on the I Like Ike button that Pogo also parodied.

I wish I had more information on the book, but neither of the two biographies issued later than Fowler’s mention The Candidate, nor do any contemporary newspaper articles explain its origin. Doesn’t matter. Jimmy Durante, old trouper that he was, knew publicity as well as George Burns. Posing for a few pictures merely ticked one more box alongside his endless fight for enduring fame.

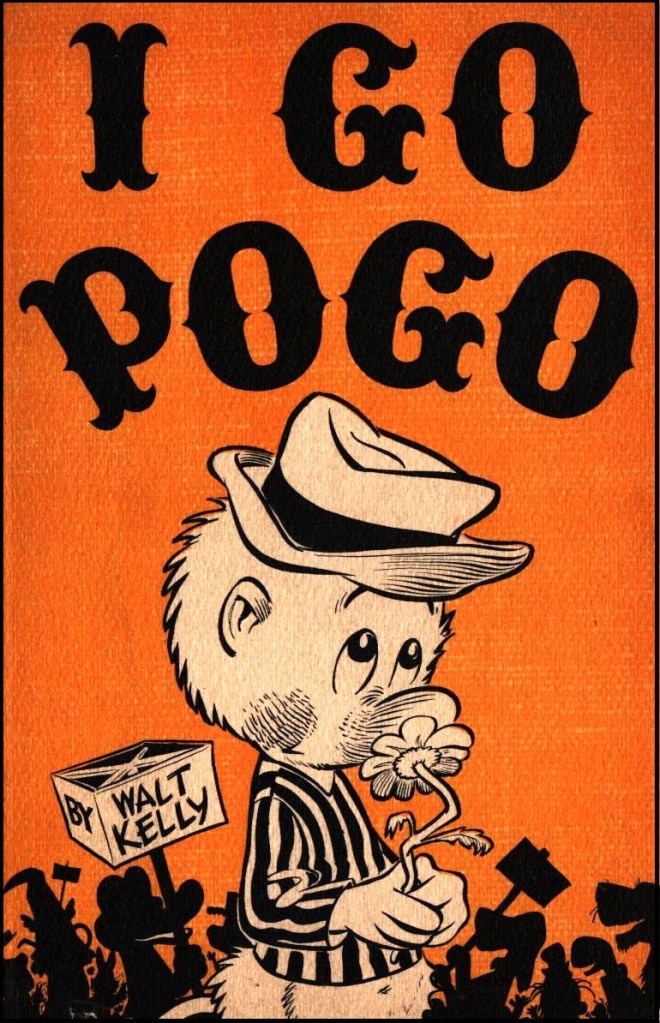

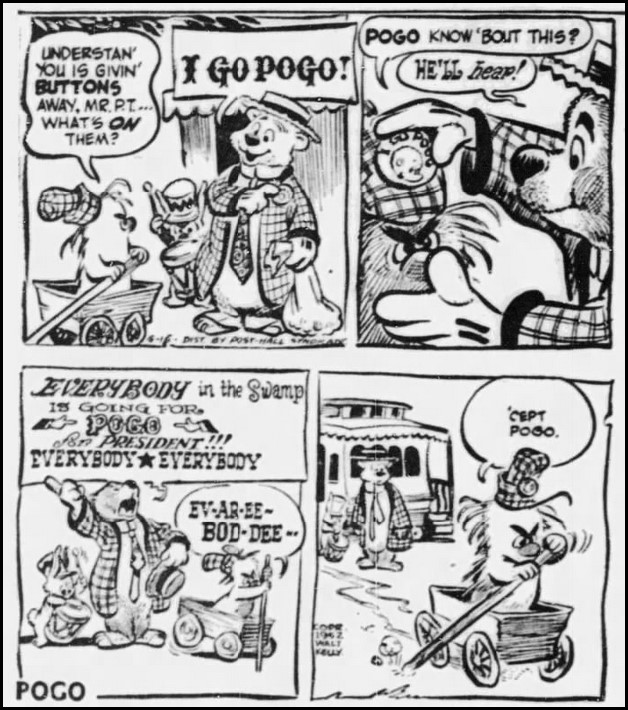

Pogo, one of the finest comic strips ever to grace newspapers, had been an instant hit since its national introduction in May 1949. Walt Kelly, a former Disney animator, moved on to comic books in the early 1940s. Pogo the Possum and Albert the Alligator had been introduced in Animal Comics #1 (1941), but even with the addition of other creatures, the irregularly appearing comic books didn’t give Kelly enough scope. He started a daily comic strip for one paper, the New York Star. It folded. Nevertheless, a syndicate took a chance. Soon the Okefenokee Swamp setting was as well known as the town of Dogpatch in Al Capp’s enormously successful social satire, L’il Abner, both using a crowd of naive Southerners to comment on human foibles.

I Go Pogo was never intended to be an original book on the campaign, rather a second collection of the daily Pogo strips, following a 1951 success just named Pogo. The strip started a sequence about putting (an extremely reluctant) Pogo up for President on April 26, 1952. Kelly decided to hype the candidacy to boost sales and awareness of his strip and reprint books. The big reveal appeared on May 15, 1952.

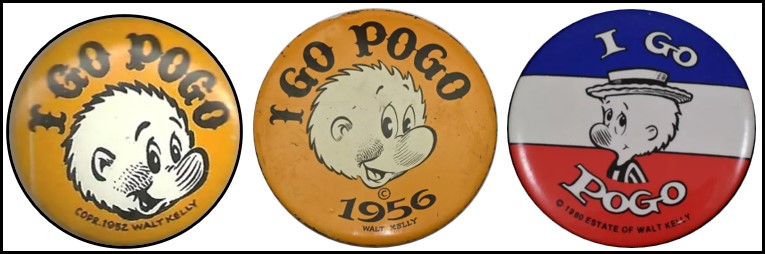

Kelly’s strip became a college craze, the way Doonesbury did two decades later. A full 50,000 I Go Pogo pins were distributed to 30 colleges at the same time P. T. Bridgeport started handing them out in the strip. (Campaigns provided such fodder for satire that new pins were handed out in 1956 and 1980.)

Students went crazy for them, none more than those at Harvard, who threw an impromptu presidential nominating convention to welcome Kelly as a guest speaker. Unfortunately, some other students decided to back L’il Abner’s Pappy Yokum as a better candidate. A four-hour riot, involving 1000, 2000, or 5000 students, depending on which undependable newspaper you want to believe, followed. Reality hit when three policeman were injured, 28 Harvard students arrested, and a group of professors threatened to sue the Cambridge Police for brutality.

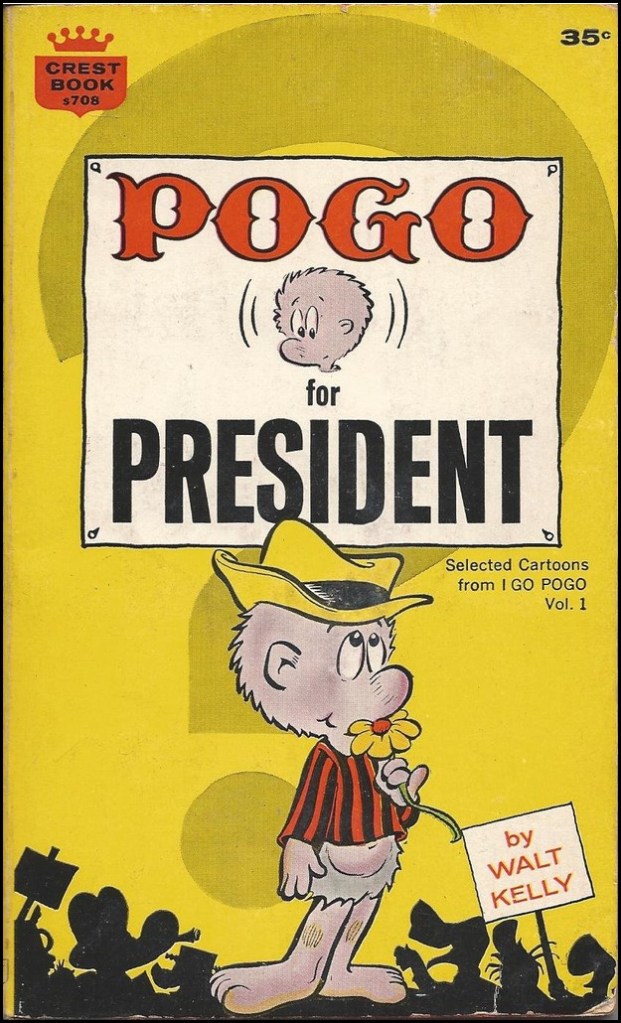

Newspapers eventually gave away 2,000,000 I Go Pogo buttons. (The slogan was a play on I Like Ike, the slogan used by enthusiasts for Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower. Jimmy Durante, as noted above, did the same gag, but Kelly got there first.) Pogo and I Go Pogo sold 100,000 copies in 1952. The book – reprinted abridged in 1964 with the more straightforward title of Pogo for President – ended with the swamp residents chaotically heading off to Chicago for an unnamed convention, leaving behind a blissfully napping Pogo. (In an equally blissful happenstance, both the Republican and Democratic conventions were held in July in Chicago, so no one could accuse Kelly of favoring a party.)

1964

All the earlier patterns were broken in 1964. While the Republican nomination was contested, the Democratic one was an absolute lock, with President Lyndon Johnson at the peak of his popularity. Nor were any books released by famous and universally beloved personalities with radio, television, and movies to showcase them. Once again, the names on the books were the least likely suspects.

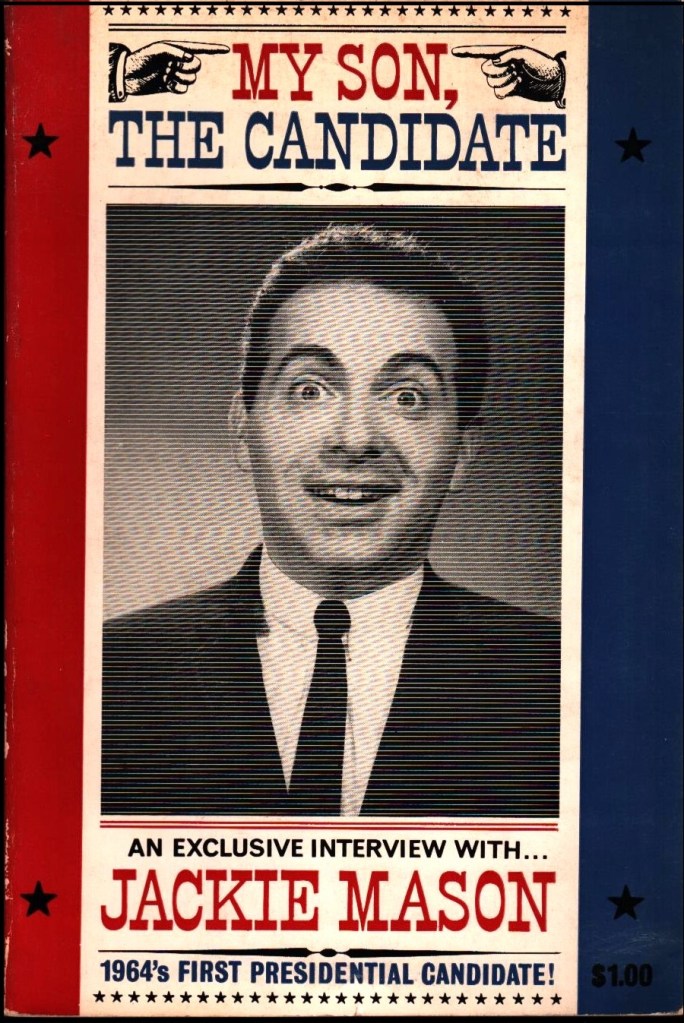

Yacov Moshe Maza was destined to become a rabbi. His great-great-grandfather had been a rabbi, and his son became a rabbi, and his son became a rabbi, and his son became a rabbi, and his three sons became rabbis. Yacov was the the fourth son and his father had a powerful will. Despite a total lack of interest in becoming a rabbi, Yacov became a rabbi. Then, in 1959, his father died. Freed to do anything he wanted, Yacov Moshe Maza became Jackie Mason. And Jackie Mason became a comedian.

His rise was spectacular. By 1961 he was appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show, The Tonight Show with Jack Parr, the Gary Moore Show, and the Steve Allen Show. By 1964 he had two comedy albums out that helped him fill theaters for his appearances. Yet he wasn’t truly famous. His shtick was Jewish humor, at least the stereotyped New York Yiddish brand of Jewish humor, told at top speed in an accent sometimes incomprehensible outside Jewish strongholds. Why the a book in which his distinctive voice couldn’t be heard? Undoubtedly for the same reasons as the others. Somebody must have persuaded him that a run for the President would be a fantastic opportunity for publicity.

It is to be hoped that he fired that person. The book, My Son, the Candidate, was supposed to establish Mason as “1964’s First Presidential Candidate.” For whatever reason, it didn’t appear until April, much too late in the campaign to make that claim. The press didn’t pick up on the book: I can’t find a single review in newspaper databases. Even the insider Broadway columns which normally promoted him made bare reference to the book.

That might have been a good thing. Readers with even moderately long memories would have noticed that the My Son was a total ripoff of Durante’s The Candidate, a page of questions next to a photo (by Gary Wagner) of Mason mugging inside a Jewish joke.

Mason’s career was derailed in October over an absurd misunderstanding during an appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. Sullivan, a vain, petty man, was to blame but never forgave Mason, who had to rebuild his image with a series of highly regarded one-man shows on Broadway. By then the campaign book was forgotten by all but collectors.

The collective vacuum surrounding the book, leaves one question remains unanswered. Who wrote My Son, the Candidate? Like Cantor, Mason wrote (or co-wrote or put his name on) a number of humorous books using real prose. He may similarly have written, co-written, or had no hand in writing this book. The book’s title, for those not up on early 60s popular culture, was undoubtedly meant to play off of the three number one albums Jewish satirist Allan Sherman had released in 1962 and 1963: My Son, the Folk Singer, My Son, the Celebrity, and My Son, the Nut. One clue may lie in the copyright, which is to Jackie Mason and Bill Adler. Adler was a professional book packager. He spun off ideas and found people to write them out and publishers to put them in print. Whether he just convinced Mason to put his name on a book to which Adler contributed all the work, or Mason provided the jokes himself is unknown.

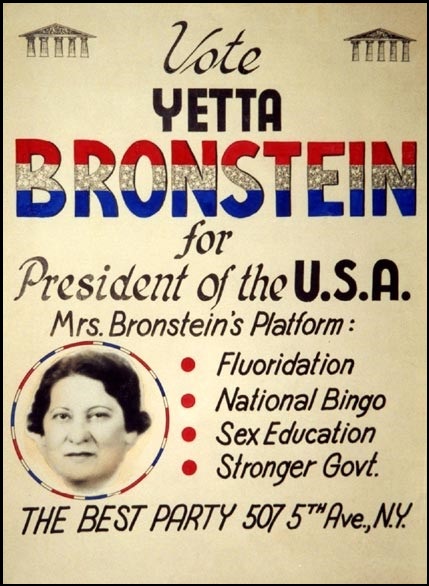

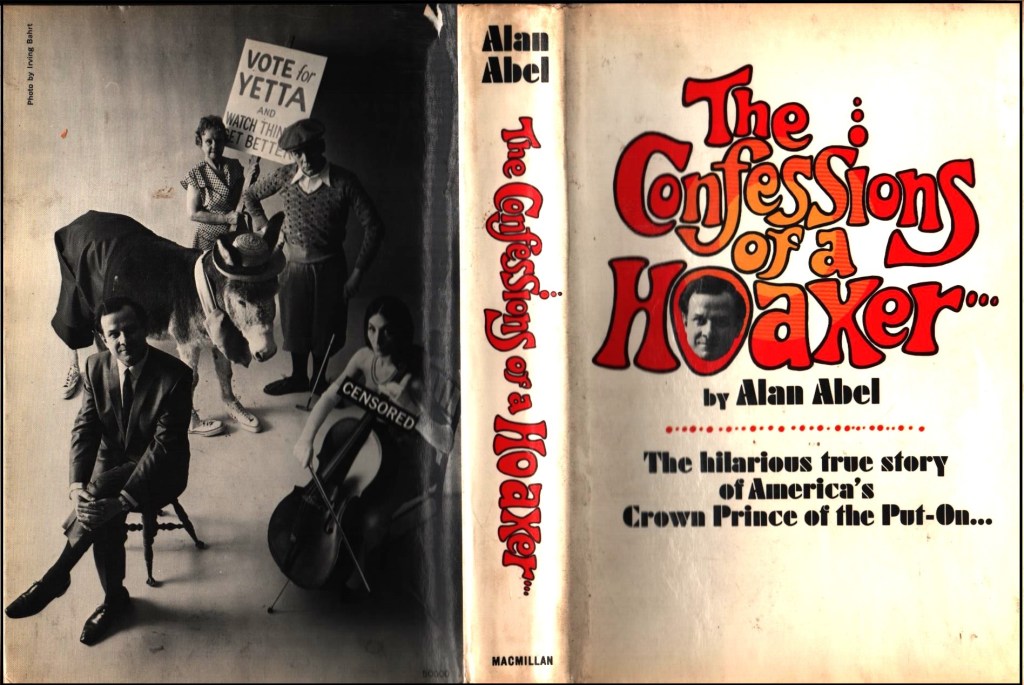

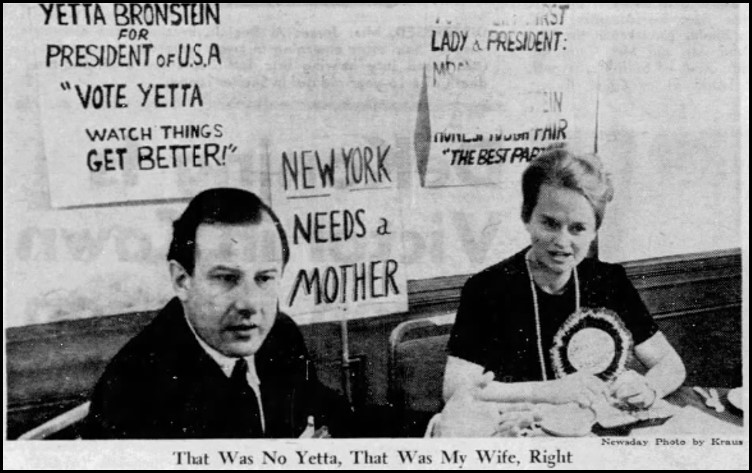

Think today’s elections are chaotic? At the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, a small group touting the Best Party, an independent try for President, were removed from their spot by the police. They were nice about it, though. “[The Nazis] have so many people here that we just have to push you down a little to keep the traffic moving” said a a state cop. The group, carrying signs reading “With Yetta, Things Gotta Get Betta,” complied, as minimal a presence as the last marchers in a Fifth Avenue parade. Yet the press noticed, thanks to the campaign manager’s vigorous and astute handling of them. Candidate Yetta Bronstein may not be a familiar name today but that’s not the fault of the national newspapers who passionately covered her presidential campaign in 1964. And again in 1968.

Let’s start at the beginning. In early 1964, Yetta – her first name was her image – started calling into Alan Abel’s Playboy radio talk show about her campaign, proclaiming that what the country needed was a mother in the White House. He wrote about this in 1970.

In her Jewish dialect, she promised to establish national bingo, self-fluoridation, hang a suggestion box on the White House fence, and print a nude picture of Jane Fonda on postage stamps “to ease the post office deficit and also give a little pleasure for six cents to those who can’t afford Playboy magazine.”

Don’t remember Alan Abel (1924-2018)? He was the country’s first and probably only professional hoaxer. At least I’ve never been able to figure out what he did as a day job. His life was a series of hoaxes, bolstered by books and fake documentaries. His specialty was creating the most absurd situations and presenting them completely straight-faced, building on real events of almost equal absurdity. Abel could stand before any audience or appear on on any tv show and convince large swathes of the public with his apparent complete sincerity. The Society for Indecency to Naked Animals (SINA) [note that the name contradicts its intent; somehow only a few columnists recognized this at the time], denounced the danger to children of animal genitalia, conveying general 1950s fears perfectly, although I’m sure that it would spark equal national hysteria today. (A young Buck Henry, later a noted comedian and writer, initially appeared as SINA’s president, although Abel later touted the group himself.) Abel played both sides. After New Wave clothing like Rudi’s Gernreich’s topless bikini made headlines, Abel made some of his own, hiring four models to pose nude to the waist. The World’s First Topless String Quartet never played a note – the models had no idea what to do with the instruments they were holding – but people swore they had seen them in concert.

Abel gleefully hoaxed the New York Times with an announcement of his own death at age 56, but to the Times’ chagrin lived 38 more years. He had “an almost unrivaled ability to divine exactly what a harried news media wanted to hear and then give it to them,” admitted the Times’ second obituary.

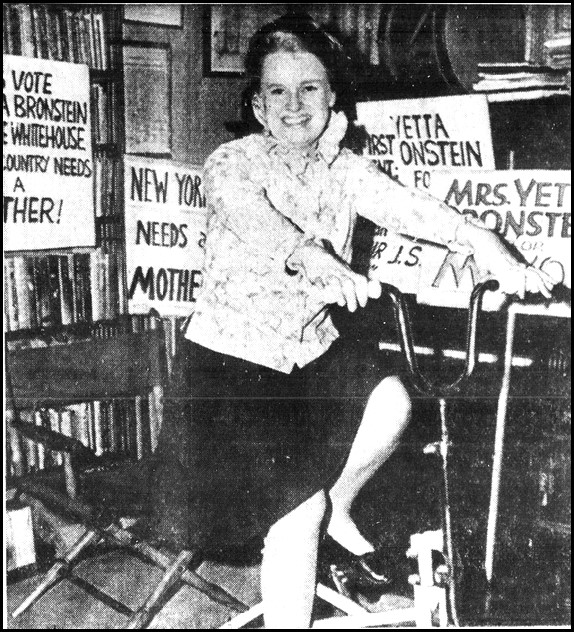

Yetta made such an impression over the radio that Abel decided to build an actual campaign on it. He had a problem that none of the earlier campaigns faced, except Walt Kelly’s: his candidate was imaginary. The voice on the telephone was his dialect-gifted wife Jeanne’s, who couldn’t be seen in public as Yetta, a forty-eight-year old Bronx housewife and mother, because she was “an attractive twenty-eight-year-old blonde ingenue type.”

Abel slithered around that limitation by spending five dollars a month to rent a literal storage closet in a tony Fifth Avenue building. He listed The Best Party – as in voters should vote for the best party – on the lobby directory, although reporters always encountered nothing but a locked door. Abel did occasionally drop by to pick up the accumulated mail and change the tape in the answering machine for a series of messages recorded by Jeanne as Yetta. Publicity stunts with friends or enthusiastic collegians as supporters kept Yetta’s name in the news. He leaked the story to syndicated columnist Paul Coates, who revealed the hoax and hoaxer to the entire country. Papers kept reporting on Yetta regardless, treating her as just one of the many weirdo candidates that populated every election. I hope Coates’ ego wasn’t bruised by being ignored.

In 1965, Abel ran Yetta as a candidate for the New York Mayoral race, which John Lindsey won over Abe Beame and William F. Buckley. The gag always worked. And with Buckley on the ballot, anything went.

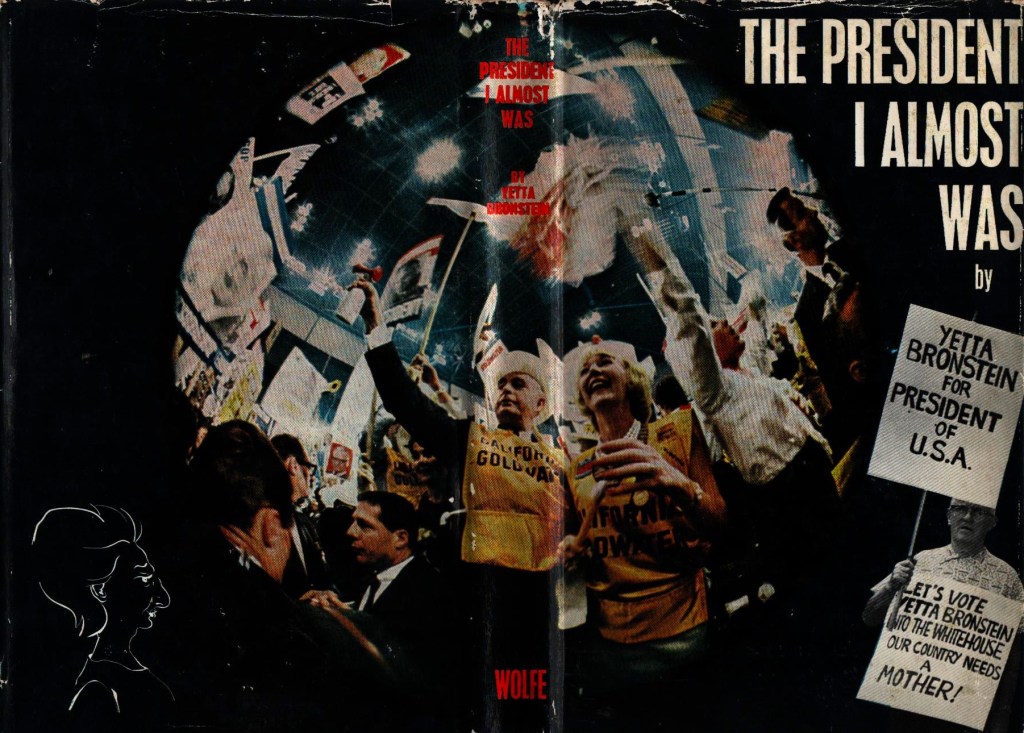

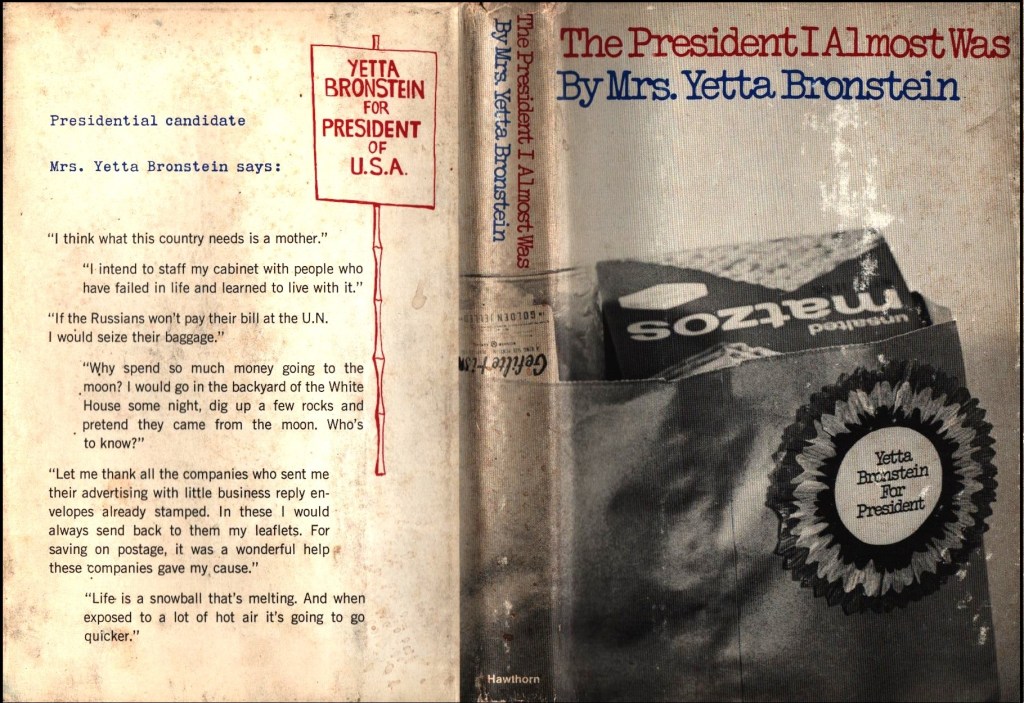

Although Abel boasted of spending only $201.27 on the New York campaign, truth is that all the outgo was a drain on nonexistent income. To make some money, Jeanne wrote a campaign book. In 1966, when Yetta was running no campaign, was not in the news, and was mostly forgotten by everybody. Perhaps that explains why no publisher was interested. In America. I have no explanation for the fact that Wolfe Publishing in London picked it up. Why they thought New York Yiddish culture jokes about life in America would sell in Britain is baffling. The “if someone else wants it, it must be good” syndrome in publishing kicked in, and an American edition appeared from Hawthorn Books, earlier a major publisher of Catholic books. Weird all the way down. In any event, the British edition is the true first edition. It also has something the American edition lacks, a four-and-a-half page “My Who’s Who” written by Yetta. The American edition, written by someone who didn’t read the original very closely, squeezes it down to a mostly different one-page “the author and her book.”

The text is a full-on barrage of gentle Yiddish kvetching about life in a New York apartment in the Bronx, reminiscent of radio and television star Molly Goldberg’s humor and books. Every once in a while, Jeanne throws some bits of reality from the press coverage and the fan letters she received. These are by far the best parts of the book. For reasons as inexplicable as its publishing history, the book caught on, with a zillions reviews from papers all over the country. Jeanne even put on some Yetta drag and did personal appearances. (The face on the poster above is reputed to be Abel’s mother.)

A few of the chapters remember to talk about her policies. They would work well for Gracie Allen, too.

Also, how about a flavored stamp? I would call them “Stamp Wafers.” The post office would make extra money by charging a cent more for a stamp wafer. Maybe you could even make soup out of a special delivery that would last a week. After all, the scientists talk to us about how in the future we will be eating pills instead of dinner. So why not a stamp for lunch?

Students like me, because as President I will abolish their grade cards. You know, a lot of college flunkers succeed in this world, while a lot of good A students turn out to be bums. I intend to staff my cabinet with successful people who have failed and learned to live with it.

Sales must have reflected the publicity because a paperback edition was published in 1967. Abel, always in love with his hoaxes – he would trot out SINA for the rest of his life, brought back Yetta for the chaotic 1968 presidential campaign. Syndicated columnist Inez Robb caught one of Abel’s publicity stunts, handing out flyers alongside a small group for Yetta marching as the last members of a Fifth Avenue parade for the 20th anniversary of Israel, and announced “The suspense is ended. At long last, Mrs. Yetta Bronstein has thrown her babushka into the ring.” Various publications kept the gag going as if no one remembered her earlier reveals. Even better, Erma Bombeck – who knew she was a put-on – reprinted Yetta’s platform in one of her enormously popular syndicated columns.

Her first act as President will be to disband the United States Postoffice [sic]. Instead she will breed ten million pigeons and train them to carry microfilm to replace conventional mail. … In her appeal to youth, Yetta asks, “Who is the only person in your life you trust? Your mother.”

Yetta never ran another campaign, but Jeanne kept abetting Abel in a lifetime of pranks. The story has a sad ending. Spending money for obscure laughs led them to losing their home. The Abels gave their lives to their art.

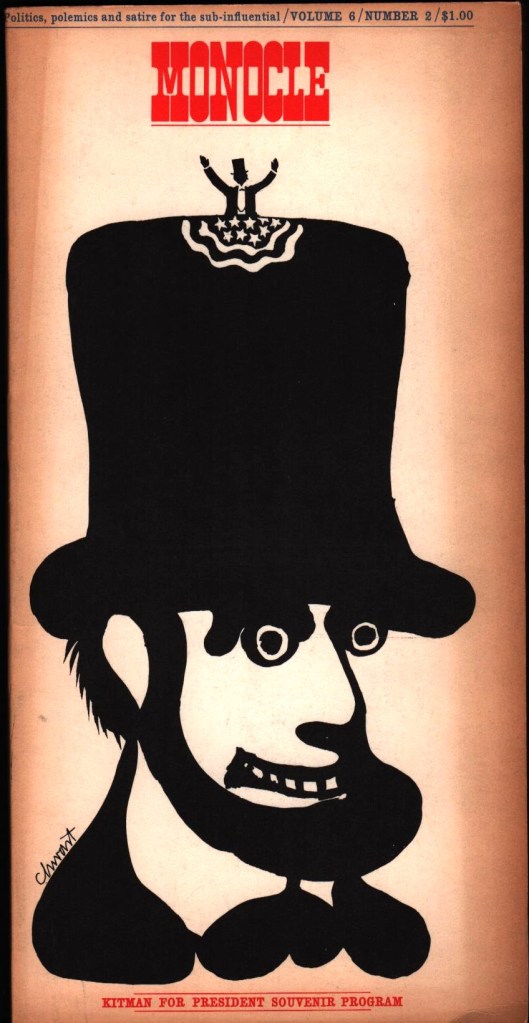

Aside 3: Monocle is the great lost humor magazine of the 20th century. I can’t think of anything like it, a work devoted to political and social satire that would be pushing boundaries today. In the early 1960s, only Lenny Bruce at his most scabrous rivaled the shots the Monocle staff took at society and he was seldom explicitly political. Perhaps the best description is the Venn diagram center overlapping 60s gadfly Ramparts magazine and today’s website Wonkette.com.

As with National Lampoon, the magazine grew out of student publications, published in various forms by law student Victor Navasky, later to be known as the editor of the very liberal magazine The Nation. Indeed, the entire staff was composed of later-to-be-known authors of fiction and nonfiction. Early editors included C. D. B. Bryan, Calvin Trillin, Dan Wakefield, Neil Postman, Richard Lingeman, Dan Greenburg, and Marvin Kitman. Sized a ridiculous 5.5 x 11 inches, 80 pages on paper suited to a pulp magazine, Monocle was difficult to hold and so tightly bound that reading near the inside of a page required origami-like calisthenics.

Kitman was the token Republican on the staff, or at least he liked to portray himself as such. He lived in suburban New Jersey, scratching out a living as a free-lance writer. Monocle had its offices in New York but, for vague reasons, was printed in New Hampshire, then as now the site of the earliest presidential primary. That must have raised the idea that with 1964 approaching and New Hampshire the site of enormous hoopla stirred by the onslaught of reporters from every media outlet in America, entering a staff member as a candidate for President could bring nationwide attention to the money-losing magazine. Kitman was chosen – or chose himself.

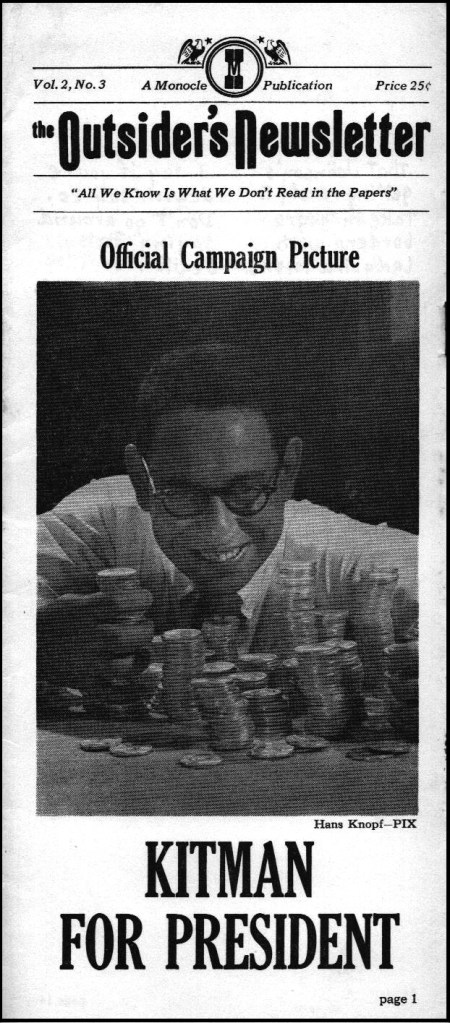

The December 8, 1963 issue of The Outsider’s Newsletter – a weird weekly Monocle sub-publication measuring 9 1/2 x 4 1/8 inches – announced the news to the world.

Kitman portrayed himself as a real candidate, going through all the paperwork to enter the primary and finding a delegate to pledge to him. “I’d rather be President than write” made for an awesome campaign slogan, appealing to free-lancers (and today’s website creators) everywhere. He was the only true Lincoln Republican, he claimed, because he was only one adhering to the Republican’s 1864 platform. His main policy proposal was to end slavery.

The press climbed all over Kitman, some of them loving the joke, some of them not quite getting it. College students got it. Young Republican clubs proclaimed him their candidate. Playboy devoted a full page to a mock interview. When the votes were counted in New Hampshire, the Secretary of State certified that his delegate received 638 votes, although every paper, including Monocle, reported differing numbers, with Monocle finally settling on 725 of some 93,000 votes. Losing caused Kitman to suspend his campaign, denying that he was ever a candidate, although he kept doing press, like a $1 a plate fundraising dinner, for another month.

Monocle staggered as well, dying in 1965, but not until publishing a “Kitman for President Souvenir Program” as their Fall 1964 issue. It is almost entirely comprised of clippings of letters and newspaper stories about the mock campaign, making a staggeringly thorough historic document of the back rooms of a campaign. Tragically, most political historians have chosen to ignore this trove of history. To be fair, that’s possibly because the program was printed only in a batch of 100 copies, of which mine is numbered 23. Several are available online, though, a suspiciously large number for such a small printing. Is it another joke? Yes. I have two copies, both numbered 23. Collectors beware.

1968

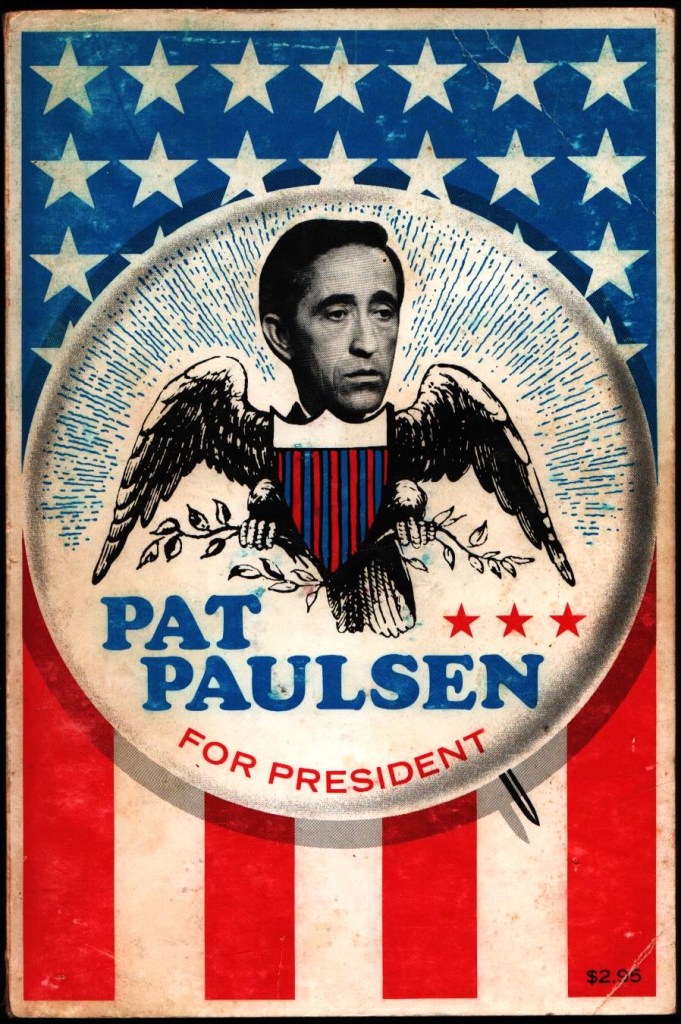

This crucial, epic, pivotal year of political insanity finally brought forth an honest campaign book, mostly because it was honestly not written by the candidate. It’s credited to Mason Williams and Jinx Kragen. Scroll down to the next aside for more on these two talents.

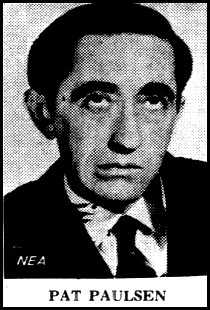

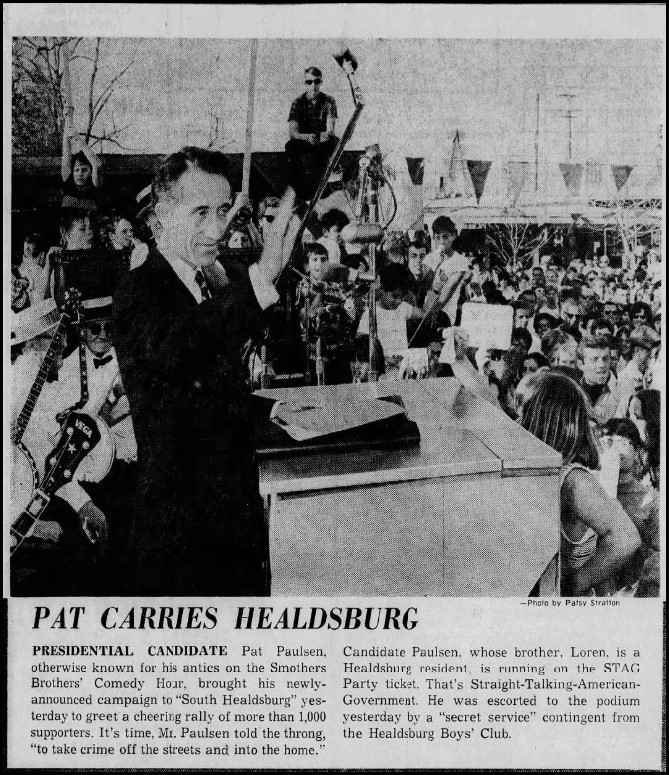

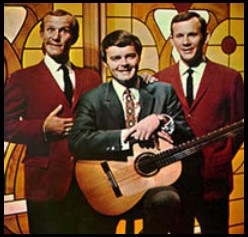

But we’ll start with Patrick Layton Paulsen, who, unlike the earlier (real) entertainers, was not famous. In fact, he may have been the least known comedian in America. Although he had spent years in various comic troupes (remember the Ric-y-tic Players?) and trios and time as a guitarist making fun of folk songs during the folk boom of the early 1960s, he entered 1967 as a 39-year-old with a wife and three young children, close to eviction and padding his gig money making two dollars a hour washing windows.

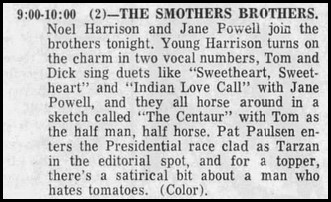

Tommy Smothers, the king of being a guitarist who makes fun of folk songs, caught Paulsen’s act at the Purple Onion in San Francisco, and thought him a perfect addition to the new show he and brother Tommy were planning. Therefore, early in 1967, Pat Paulsen made his introduction on season 1 of The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour by saying “Hello” to the audience. And nothing else. At first the show had no idea what to do with him but soon realized that his dour, deadpan face could be used to spoof the superserious purveyors of editorial comment that had recently become standard on news programs. Soon the show received up to 15,000 letters a week asking for copies of his editorials.

Paulsen did not write his own commentary. The show, as all television shows did, had a staff of writers who provided the words and ideas for skits and sketches. The writers room for the Smothers had some of the youngest minds in television, most of them safely under 30 so they could be trusted. They were corralled in by headwriter Mason Williams, all of 29 and on his second television gig.

At some point in the show’s second season, Williams had a bright idea. Paulsen’s spoof of serious people might work even better as a candidate for President.

Although the show teased his entrance into the campaign over a number of shows in early 1968, this was perhaps the worst-kept secret in television history as newspaper announcements of upcoming shows gave the joke away before the October 1, 1967 episode.

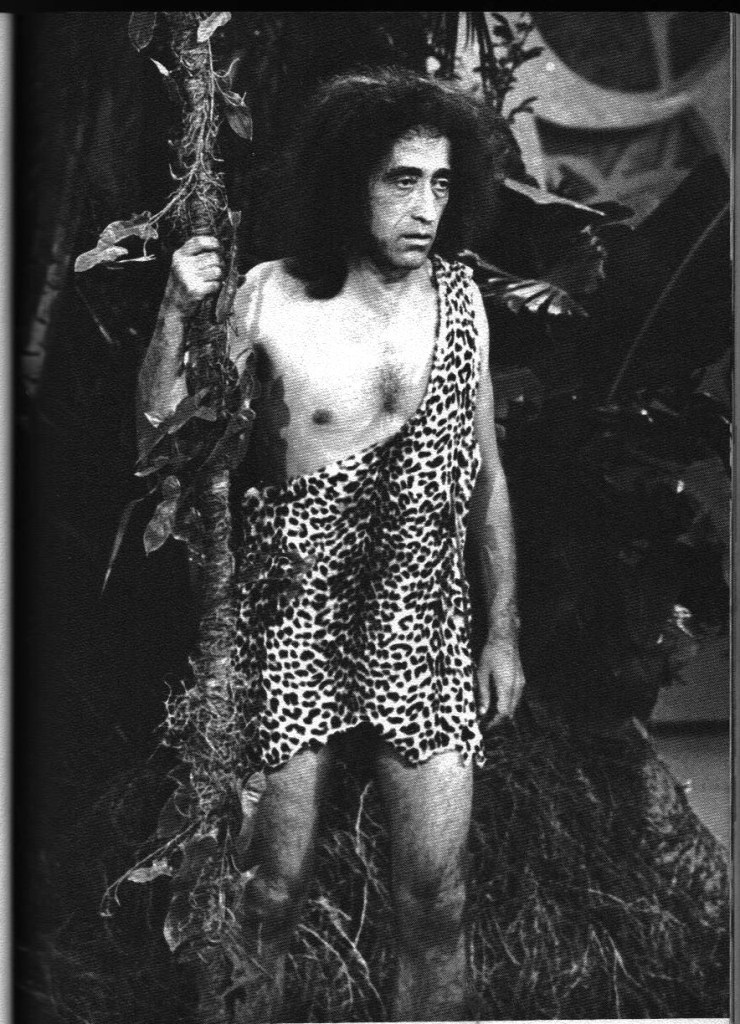

Nobody wanted to see Paulsen dressed like Tarzan, which of course was part of the joke.

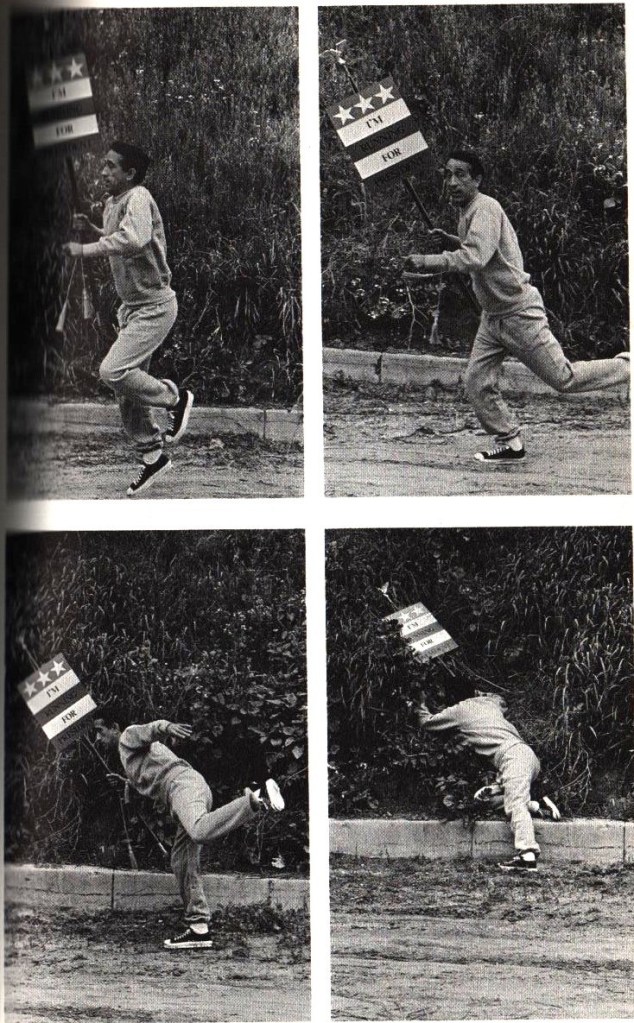

Paulsen’s candidacy/non-candidacy finally culminated in season 2 with an announcement on the March 3 show, which was just before the Smothers’ odd-length season ended. By that point Paulsen was heavily campaigning, at least within commuting distance of his Los Angeles base. As with Pogo, Yetta, and Kitman, collegians swarmed to Paulsen.

Although there’s an earlier reference to the Straight Talking American Ticket (STAT) – a sneaky reference to Paulsen’s earlier day job of running a photostat machine – the campaign finally decided on the naughtier Straight Talking American Government or STAG Party.

On the March 10 show, the last show of the season, he went to the White House. Not as President, of course. On film, wandering around monuments and talking to people.

Then Lyndon Johnson declared he wasn’t running for re-election on March 31 and the political world went nuts, just in time for the Smothers’ summer vacation so neither they nor Paulsen could comment on national television. Coincidence? I think not.

Paulsen booked a heavy schedules of gigs around the country and showed up at the Conventions for more publicity. Gracie Allen filled newspapers pages for two solid months during her campaign. Paulsen spent a year taking his character on the road. My estimate is that no fake presidential candidate has ever received so much attention from newspapers. Paulsen was a center of attention wherever he went. He didn’t need a campaign book, but Williams and Kragen concocted one anyway out of scraps and quotes. Pat Paulsen for President covers the campaign from the Smothers’ season 1 to the end of season 2, with a mention of Johnson’s announcement as a sort of coda.

You might think that the wildly original Mason Williams would come up with a new slant on the campaign book. No such luck. The book shows evidence of being assembled over a weekend in April. And it is filled with the standard set of pictures of Paulsen mugging for the camera, such as this one showing that he is “running for President.”

Although the book claims that it is “Copyright 1968 by Pat Paulsen”, no such filing can be found in the Catalog of Copyright Entries. Nor is any publisher listed inside the book. I would say they ran it off on the office copier, except that a Mason Williams biographer gave the book a printing of 60,000 copies. When it appeared is also mysterious. Newspapers in June announced a July publication date; newspapers in July gave a date of August 1. Yet I cannot find a mention of it earlier than August 8. The book sold, no doubt. There was a second printing. The first printing is given as July 1968, the second as August 1968. The second printing includes something left out of the first: the publishers, Kragen/Fritz, Inc. of Beverly Hills. Is this the same Kragen as Jinx? No. It’s her husband. Again, scroll down to Jinx Kragen for the backstory.

Fortunately, the second half mainly features photos of his campaign appearances, spiced with text of his speeches on the show and interviews with reporters. Some of his rhetoric on the stump was truly barbed.

Although I am a professional comedian, some of my critics maintain that this alone is not enough.

Supersonic transportation will, in the future, make it possible for our nation to make its diplomatic errors much faster.

The only time you have a credibility gap is when you don’t know whether or not the government is lying. Obviously we do not have this problem, because there is no longer room for doubt.

Despite garnering only four write-in votes in the Wisconsin primary, the comedian who had made $10,000 in his best year – gross, not net after the expenses of being on the road for eight months – was now milking his opportunity, riding his viral fame throughout the summer, traveling across the country with his deadpan act and pat answers to reporters’ questions. He also appeared on multiple television shows, all this on top of the $400,000 a season he made with the Smothers. He bought his family a house.

Paulsen fortunately gained access to no state ballots so his [non]campaign did not run afoul of the Equal Time provision, allowing him to be a highlight of the Smothers return in late September to a different America. A month later, the show was bumped for a special replacement: an hour on Paulsen’s campaign on October 20, 1968.

Aside 4: Wait, back up to Pat Paulsen for President. So what’s the story on Mason Williams and Jinx Kragen?

Mason Williams will always be remembered for his incredible and unexpected smash instrumental hit “Classical Gas.” As with many one-hit wonders, that success overwhelms the rest of his long career as an author and musician and artist and creator of art books. Not to mention twenty-plus credits as a television writer, mostly on variety shows. For our purposes, unfortunately, none of his many other books can be classified as humor, except possibly the seriously odd chapbook The Mason Williams F.C.C. Rapport, a screed on censorship.

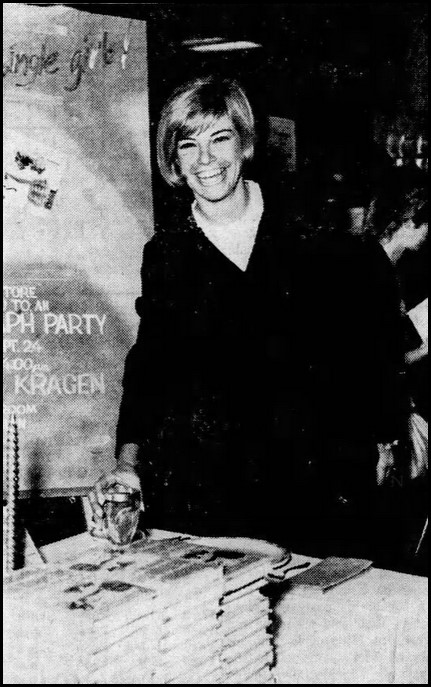

Jinx Kragen is a two-hit wonder whose association with the Smothers needs some backstory. In January 1962, Judith Ann “Jinx” Adams, a 1961 graduate of Stanford and chosen to Mademoiselle’s national College Board, married gloriously to Kenneth Allen “Ken” Kragen, a graduate of UC Berkeley and the Harvard Business School. News then for the society pages only, mainly because Ken’s father Adrian, a famed law professor, was Berkeley’s Vice-Chancellor.

Probably to Adrian’s chagrin, Ken used his degrees to go into show business, becoming the manager of the folk music group The Limeliters. Traveling in those circles he naturally met the Smothers, and became their manager in 1964. And more, as from his obituary in Variety.

One of Kragen’s first key ventures was the Kragen-Fritz management company that he created with his business partner Ken Fritz in the ’60s. For over five years they worked together as co-executives of the “Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” as well as the “Glen Campbell Good Time Hour,” both on CBS. In addition to the Smothers, their clients included Kenny Rogers and The First Edition, Pat Paulson and Mason Williams.

Jinx is never mentioned in histories of Kragen’s career. Yet she started writing for him immediately. Digging out her credits is difficult, since they didn’t appear in standard indexed sources. Her name is on the liner notes for the Smothers’ two 1964 albums: It Must Have Been Something I Said and Tour de Farce: American History and Other Unrelated Subjects. And she wrote the copy for a series of large-format brochures sold as souvenir programs on their endless live performances, the proceeds going to charity.

As late as 1966, she did the same for a oversized promotional brochure for Bill Cosby, also produced by Kragen/Fritz, the money going to Temple University scholarships. More of her work is probably hidden and yet to be found.

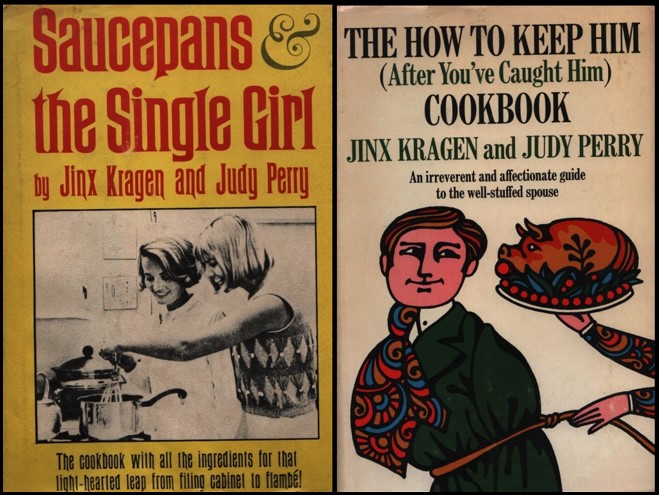

Something happened between 1964 and 1966. Another of Jinx’s side projects blew up into a national bestseller. Judith Ann and her college buddy Judy Pascoe hit the big time in 1965 with Saucepans and the Single Girl, a cookbook with real, but later admittedly awful, recipes for the woman in search of a meal ticket. (Their words, not mine.) Humorous portraits of various types of eligible men graced each chapter along with commentary on what the single girl had to go through to catch a man. A “strict” monthly budget was $200 for clothes, $20 for taxis, $30 for hairdresser, $50 for rent, and $10 for food.

A surprise smash hit with gleeful reviews in the Times and elsewhere, the book’s publishers sent the two Judys on a publicity tour in the fall.

One slight problem. Jinx had had all of seven months on the market before her then three-year-old marriage and Judy, now Judy Perry, was not only married but visibly pregnant. Not a good look for a 60s single girl. Problems are opportunities, as some self-help guru undoubtedly said. The two immediately wrote a 1966 sequel, titled The How to Keep Him (After You Caught Him) Cookbook. Yes, all very Mad Men. Consider that show a long-running documentary.

1972

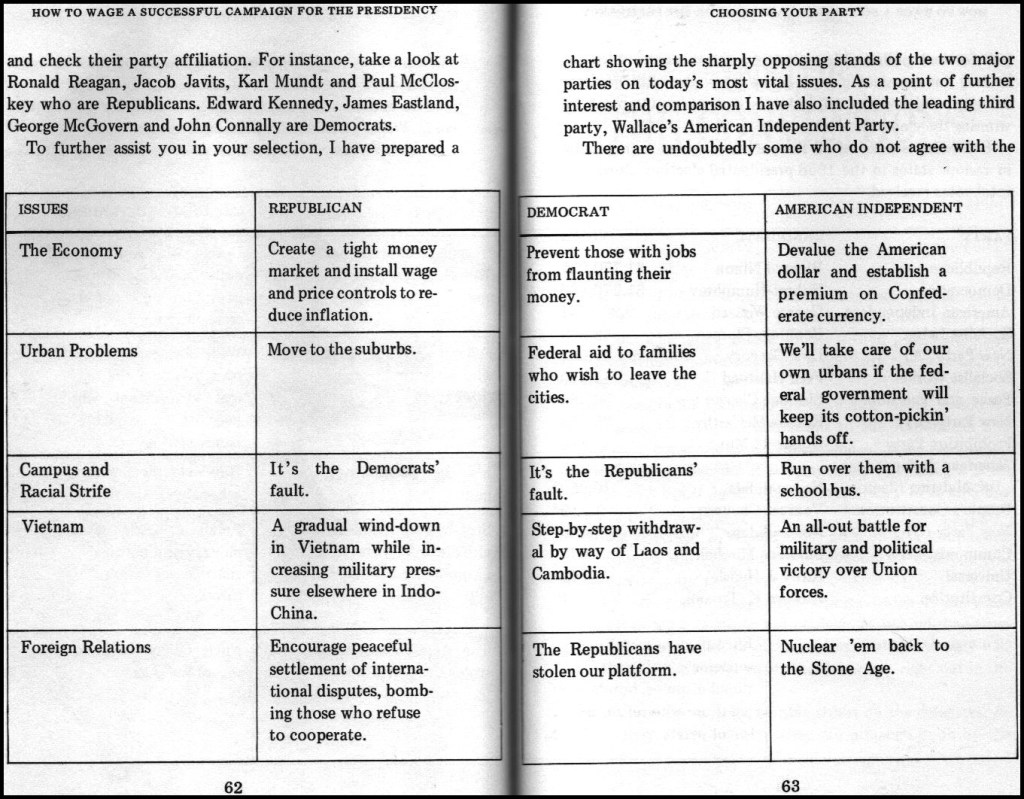

Pat Paulsen obviously did not win the presidency on November 5, but running for President was such a great, lucrative, and self-promoting gig that Paulsen campaigned again in 1972, 1980, 1988, and 1992, surpassing Yetta Bronstein’s record. And even in 1996, though he was so ill that he would die the next year. Franklin Roosevelt ran for four terms; Paulsen knew he was following a great tradition. Besides, Paulsen knew he had what most small-time actors dream of: a great, well-paying gig, the first stand-up politician. So much so that in 1972 he released a virtually unknown companion book. How to Wage a Successful Campaign for the Presidency – the title riffed probably unknowingly on Gracie Allen’s How to Become President – gave little useful advice on the subject, but is by far the best of all the campaign books, still funny after all these years and horrifyingly still relevant.

Because he mentioned few names – with the following major exception, the jokes resonate over the decades. We really need to do something about our politics.

Since I’m a writer trying to give credit to writers, let me add the names of John Barrett and Cecil Tuck, who Paulsen acknowledges as his speechwriters. Both of them worked on the Smothers’ show and on further Paulsen projects, including the tv special and his record albums.

Alsorans

I don’t know of any more recent campaign books by comedians. Books aren’t the promotional bonanza they were in the past. Not that comedians stopped talking about the Presidency or cooking up heavily promoted campaigns, just that they no longer put out associational books. These three are the closest: almost campaign books.

Why Not Me? by Al Franken, 1999

After leaving Saturday Night Live after fifteen years as a writer there, Al Franken dropped into politics with a bang, Rush Limbaugh Is a Big Fat Idiot and Other Observations becoming a number one bestseller in 1996. The book made Franken an unexpected hero of the left, a role he pursued for the rest of his career, and one that saw him elected as a Senator from Minnesota in 2008. Back in 1999, though, he followed Liars with Why Not Me? Politics was again the subject of savage satire as he detailed his long campaign to win the 2000 election and his brief 2001 stay as the Democratic President (beating Newt Gingrich). Franken is eerily prescient in detailing a campaign lacking in issues but rife with insulting attacks on all opponents and a presidency that riles the entire world before the inevitable impeachment. Or perhaps he was just an astute political reporter, since one of his fake headlines is “[Pat] Buchanan Announces Formation of Anti-Abortion, America-First Part, Further Dividing GOP Faithful.” The partisan split in the America of 2024 has been a long time coming.

I am America (And So Can You) by Stephen Colbert, 2007

In this crazy compilation of characters who play characters who pretend to run for office, none needs more explanation to the uninitiated than the character of “Stephen Colbert.” The real-life Colbert (pronounced with a silent “t”) graduated from Northwestern University in Chicago and immediately immersed himself in the city’s famed improvisational comedy culture. It took a decade for him to find true success, which came when he became a correspondent on The Daily Show in 1997. He described his character as “a well-intentioned, poorly informed, high-status idiot.” After Jon Stewart took over the show, the pair decided to dial the character up to 11. The Colbert Report (both “t”s are silent) starred Colbert as “Stephen Colbert,” a loudly always-positive and never-wrong parody of right-wing commentators like Fox’s Bill O’Reilly. On his first show, October 17, 2005, Colbert inserted himself into political history by coining the word “truthiness.”

Truthiness is ‘What I say is right, and [nothing] anyone else says could possibly be true.’ It’s not only that I feel it to be true, but that I feel it to be true. There’s not only an emotional quality, but there’s a selfish quality.

Colbert instantly joined Stewart as the twin darlings of a left-wing appalled by the Bush administration, ranting ironically from a right-wing perspective that was meant to ridicule the right. It was a masterpiece of satire, so deftly done that many conservatives praised these very rants. In 2007 Colbert the character announced he would run for president but only in his home state of South Carolina. When Comedy Central wouldn’t pay the filing fee to run as a Republican, he tried to enter the Democratic primary but was rejected as not a serious candidate. Astute of them. Speaking of media synergy, in which one medium helps plug another, Colbert – helped by his large staff of writers – released a parody of right-wing bluster, I Am America (And So Can You), timed to hit bookstores simultaneously with the South Carolina primaries. Hit it was, reaching the top spot on the Publishers Weekly lists. Nevertheless it is even less a campaign book than the following.

President Me by Adam Carolla, 2014

Adam Carolla did not, as Al Franken did, attend Harvard. He’s a community college dropout who had a long series of blue-collar jobs before turning to comedy. He struck gold as a loudmouth radio and television host, with a series of hits like Loveline on MTV and The Man Show and Crank Yankers, both on Comedy Central. His right-wing persona was succinctly captured by the title of his first humor book, In Fifty Years We’ll All Be Chicks… And Other Complaints from an Angry Middle-Aged White Guy (2010). It cannily rode the enormous popularity of a podcast he started the previous year and made the New York Times bestseller list. A second book, in 2012, Not Taco Bell Material, was more autobiographical. His third book, President Me: The America That’s In My Head, was released for some reason in the non-campaign year of 2014. Like W. C. Fields’ book, President Me is basically a series of rants bookended by references to the presidency. No actual campaign was ever intended.

- Intro

- 1876

- Max Adeler [Charles Heber Clark]

- 1928

- 1876

- Books

- 1932

- Eddie Cantor (Your Next President!) [David Freedman – see Asides]

- 1940

- Gracie Allen (How to Become President)

- W. C. Fields (Fields for President)

- [Charles Algernon Sunderlin – see Asides]

- 1952

- Jimmy Durante (The Candidate)

- Pogo (I Go Pogo) [Walt Kelly]

- 1964

- Jackie Mason (My Son, the Candidate)

- Yetta Bronstein [Jeanne Abel] (The President I Almost Was)

- Marvin Kitman [Kitman for President Souvenir Program – see Asides]

- 1968

- Pat Paulsen (Pat Paulsen for President) [Mason Williams and Jinx Kragen – see Asides]

- 1972

- Pat Paulsen (How to Wage a Successful Campaign for the Presidency) (1972)

- 1932

- Asides

- Alsorans

- Al Franken (Why Not Me?, 1999)

- Stephen Colbert (I Am America [And So Can You], 2007)

- Adam Carolla (President Me, 2014)

You must be logged in to post a comment.