Oliver Herford, according to Forgotten Humorist Corey Ford, was:

[A] figure of fantasy, short and wispy and as gray as lint: disordered gray hair, an ill-fitting gray suit, pearl-gray spats, a monocle on a long faded ribbon. (Someone once asked him why his suits were always the same color. “Saves me a world of trouble,” Herford answered. “When spring comes around, I merely write my tailor, send him a small sample of dandruff, and tell him to match it exactly.” He showed up one day wearing an outrageous gray derby derby, and explained that it was a whim of his wife’s. Friends advised him to throw it away. “Ah, but you don’t know my wife,” he sighed. “She has a whim of iron.”

The Herford Ford described was the editor of Life magazine, the preeminent humor magazine of the 1920s, the jumping off point for the witty young of the day before The New Yorker caught the changing tenor of humor in the 1930s. Ford got his start there, and Robert Benchley, and Dorothy Parker, and Will Rogers did his 1928 faux-presidential campaign out of its pages, and so on. Never as sophisticated as Vanity Fair, but more adventurous than its competitor Judge, Life spoofed, sauteed, and parodied the world in almost exactly the way National Lampoon would do a half century later.

Herford had been someone Life would have welcomed into its pages a couple of decades earlier. In fact they had. In 1890, the Boston Evening Transcript, his local paper, wrote, “All readers of Life must have noted the clever drawings of Oliver Herford,” also mentioning that his grandmother was well known as an author and artist. The young Herford, absolutely not old and gray, was much the dandy when he supplemented his incessant magazine work with book illustrations for famous contemporary humorists like John Kendrick Bangs and Joel Chandler Harris.

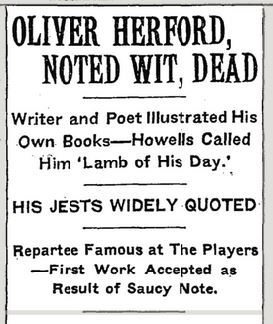

Aside: Herford was born in England on December 2, 1863. At least that’s what all of his obituaries said in 1935. Some modern sources alternately list the date as December 2, 1860. Take your pick. Maybe he shaved three years off his age in a fit of ego. Either way, dying with headlines calling you a “noted wit” is the way to go.

“Saucy note”? In a Times headline? What could that possibly be, if printable at all? I won’t leave you hanging. The obituary reports that after many rejections from The Century Magazine, Herford “bundled the entire collection together and sent it back with a note to the editor, reading ‘Sir: Your office boy has been continually rejecting these masterpieces. Kindly see that they receive the attention of the editor.’” Amazingly, the editor – Richard Watson Gilder – accepted both the cheek and some of the submissions, launching Herford’s career.

Known mainly as a poet, aphorist, cartoonist, and illustrator, Herford had had a hand in dozens of books over a forty-year career. That description would normally disqualify him for this site, but he just squeaks in through a few fun books of prose humor found by scrabbling through that heaping pile.

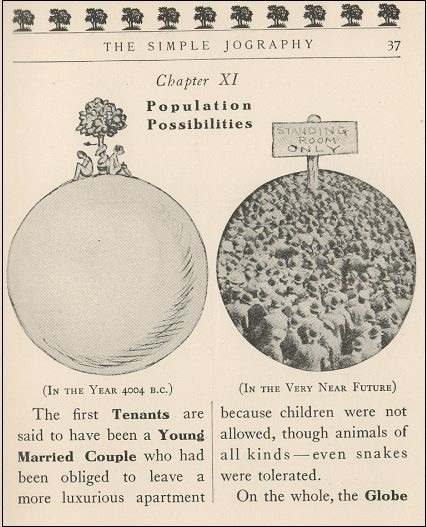

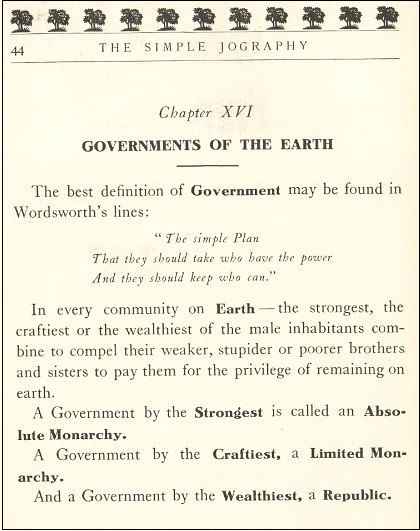

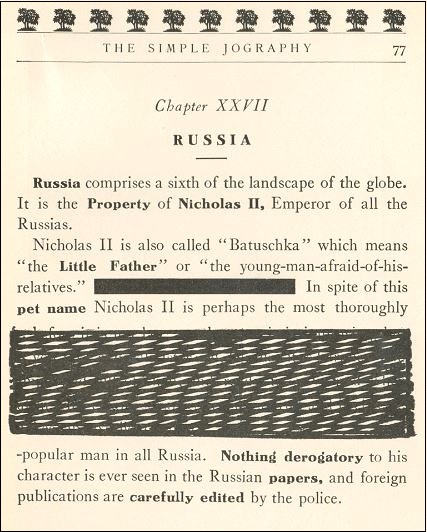

The Simple Jography, or How to Know the Earth and Why it Spins (1908) takes the world and satirizes it, no small feat in a small volume of 100 pages. It reflects the world in which it was written, so the barbed stereotypes sometimes are simply outdated but sometimes still amazingly applicable to modern times, with hardly a change.

In 1919, to reflect the changed world after World War I, Herford rewrote the book and issued it until the title This Giddy Globe. Aspiring collectors will see online that many book dealers list this as a reissue of The Simple Jography. Not at all. Virtually every page is rewritten and there are many new passages and even new chapters.

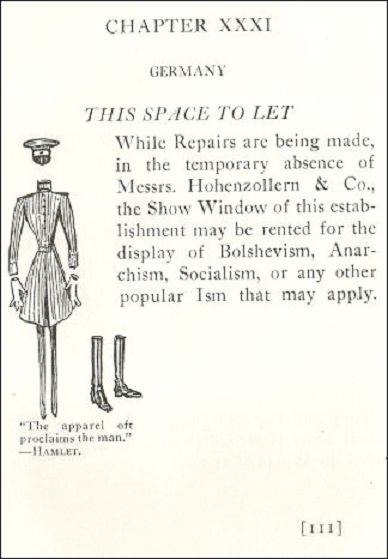

Frighteningly prescient is his revised chapter on defeated Germany. The hallmark of a true satirist is their ability to tell dark truths in the space of a short laugh.

The book ends on p. 137 with “APPENDIX/See next page”. The next page reads “THE APPENDIX/has been removed”.

Herford wrote many borderline books as well. Cupid’s Cyclopedia (1910), with John Cecil Clay, and The Deb’s Dictionary (1931) are in the style of Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s Dictionary, collections of humorous definitions that are really just one-liner jokes.

So were most of the contents of the extremely annual popular series of almanacs Cynic’s Calendar of Revised Wisdom, with Ethel Mumford and Addison Mizner. Strictly speaking, Herford had nothing to do with the first volume (released in 1902 to be a weekly calendar for 1903); the other two – without his knowledge – added his name as the author to trade upon his fame. Herford took the joke in the spirit offered: he sued for 90% of the royalties. After winding up with an equal three-way settlement, Herford added his own contributions for the next several years worth of calendars.

A bit more text can be found in another series of almanacs, with John Cecil Clay. The first in the series, Cupid’s Almanac and Guide to Hearticulture for This Year and Next (1908), has pages of text, and I’m counting it here. Cupid’s Fair-Weather Booke (1911), has poems outweighing text, so I’m not. An earlier collaboration with Clay, Happy Days (1907), is just poems and pictures. Out. Neither Here Nor There (1922), fortunately, is a simple collection of Herford’s short humorous pieces with no explanation needed.

Bibliography of Humorous Works

- 1908 – The Simple Jography (illustrated by himself; pictures by Cecilia Loftus)

- 1908 – Cupid’s Almanac and Guide to Hearticulture for This Year and Next (with John Cecil Clay and with illustrations by both)

- 1919 – This Giddy Globe (illustrated by himself; pictures by Cecilia Loftus)

- 1922 – Neither Here Nor There

You must be logged in to post a comment.