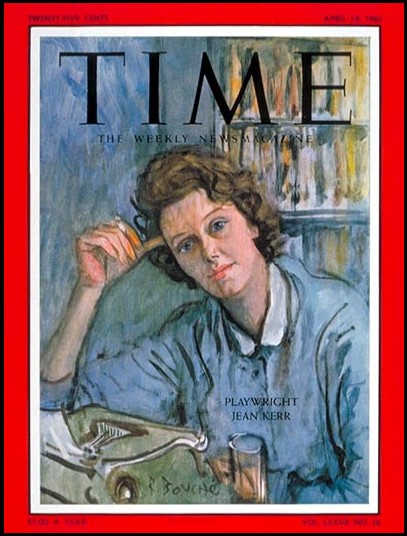

Most of the authors on this site had their heydays a hundred years or so ago. Generations passed. They slipped out of memory. Fair enough. Most famous people do. 1961, though, is well within my lifetime. Few women had the distinction of making the cover of Time magazine in that era unless they won a Nobel Prize or were the head of a country. Jean Kerr got the cover and a hagiographic 5,000-word article inside because she wrote humorous essays. She was riding high after two number one bestsellers and a profitable Hollywood movie about her life. And her greatest success lay ahead. How could we have forgotten her so soon?

Back to the beginning. Jean Kerr’s story starts with an incident people would find troubling today although it raised scarcely an eyebrow in the early 1940s. A fixture in the theater department at Marywood, a Catholic women’s college in her home town of Scranton, PA, 18-year-old Bridget Jean Collins fell in love with a visiting professor a decade her elder. The professor, Walter Kerr, was busy shaking up the theater world, having written twenty plays for local and college productions with grand ambitions thereafter.

Upon her graduation, Walter saw to it that Jean, as she was known, entered the graduate theater degree program where he taught, Catholic University, in Washington. By that time they had collaborated on a musical comedy that was produced in New York, Walter had proposed, she had accepted, and they were thence married in 1943, looking forward to a lifetime in theater. (Jean got her MFA, and did some teaching herself.) No suspense where this is going: they stayed gloriously married until Walter died 53 years later. Walter was Jean’s first and only adult love.

The Kerrs collaborated on plays, musicals, and revue sketches, with Walter sometimes directing. One play Jean wrote by herself was an adaptation of the humorous memoir Our Hearts Were Young and Gay by forgotten humorists Cornelia Otis Skinner and Emily Kimbrough. In an original play of hers, Jenny Kissed Me, from 1948, 18-year-old Jenn falls in love with a 34-year-old faculty member. Hmmm. Despite poor reviews, the simple plot full of sparkling lines got the play adapted seven[!] separate times for early television. King of Hearts, a moderate Broadway hit, was co-written by Jean and Eleanor Brooke, another of Walter protégés, and directed by Walter. (No matter what Wikipedia says, it did not win a Tony Award. That was a different play with the same name.) Two years later King became the Bob Hope-starring movie That Certain Feeling. (Yes, there is a romance with, this time, a twenty-year difference in age.)

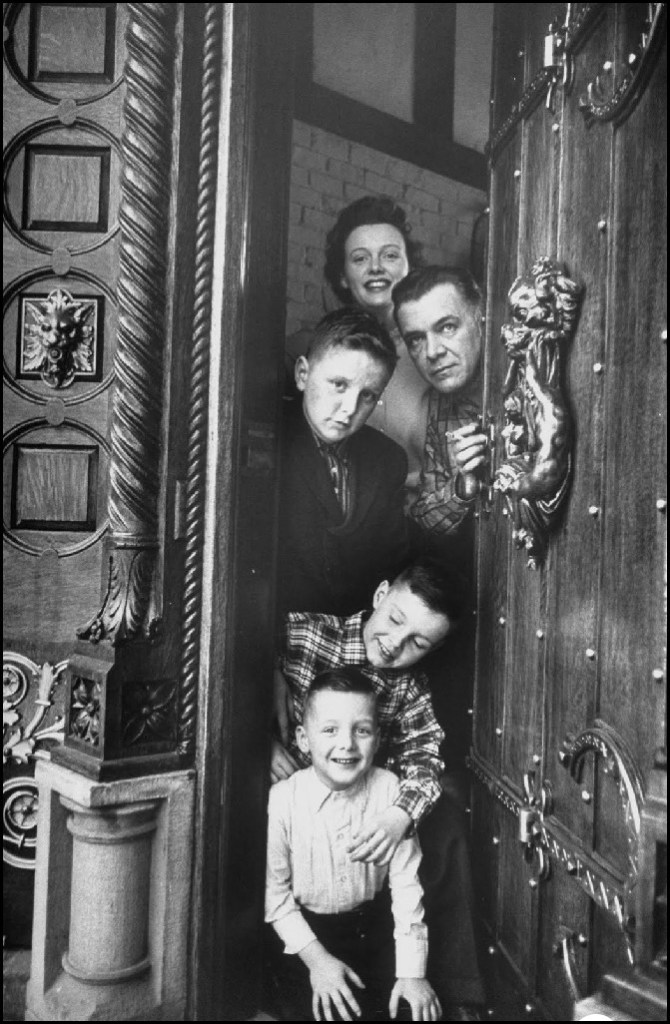

After a decade of marriage, the Kerrs’ busy and successful lives bounced between two preoccupations, theater and children. Christopher, born in 1945, was followed in 1950 by twins Colin and John. Walter, feeling the pinch of multiple young children on a professor’s salary, fell upward into the prestigious job of theater critic for the New York Herald Tribune and the family moved to a small New York apartment until Gilbert’s arrival in 1953 made that untenable in the long term.

Aside: In 1953, a wholly different Jean Kerr married Sen. Joseph McCarthy. Please don’t ever get them mixed up.

All this mundanity is mere buildup. The Kerrs’ lives would change forever in 1954. They had spent a year looking for a nice, roomy suburban house until they stumbled on a broken-down pile of rooms upon rooms, a mere 35-minute express train to New York. As usual, the good luck occurred at exactly the worst time in a life already at capacity between work and home. Jean not only survived the crush but turned it into an opportunity.

My play, “King of Hearts,” had two kids in the cast and this apparently prompted a magazine [in the person of Vogue’s editor Allene Talmay] to ask me to do a piece on kids. I was crushed. I wanted to do something profound, something, say, on the future of the theater.

But my husband said to go ahead. I finally agreed, but only if I could use the money I was going to get to buy a freezer. After that other magazines started asking, and that is how the books began.

Good freezers cost $400-500 in 1954. Vogue must have been happy they got her early. In a very few years her price would go up to $3,000.

“Please Don’t Eat the Daisies” appeared there in Vogue’s July 1954 issue. And then another Vogue piece in 1955, and 1956, and 1957, and 1958, and 1959. And in Harper’s and Harper’s Bazaar and Ladies Home Journal and McCall’s and the New York Times Magazine and TV Guide and Good Housekeeping and Holiday and Family Circle and the Saturday Evening Post.

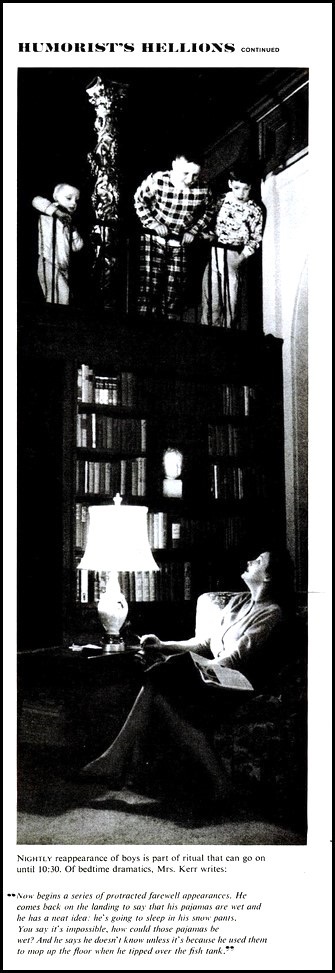

Writing humorous essays became a third and even more successful career. As with so many other women writers, Jean squeezed out time and space to write. She parked her car and, summer and winter, scribbled on a pad to get her daily writing done. (Posing her with a typewriter was a photographer’s cliche. Walter typed her pages from his den. Of course Walter had a den.) Within a short time, Jean created an alternate persona of Everywomen, her harried existence of housekeeping, shopping, being a critic’s wife, and tending to her four impossible sons (her phrase) hitting the sweet spot of suburban identity the women’s magazines appealed to.

Being an Everywomen masked Jean’s true identity. Jean always said she wanted to become a writer so she didn’t have to get up in the morning. So she didn’t; she woke about one pm. (Walter rose at ten am.) The maid – there was always a maid – got the children up and ready for school.

Her persona was sealed when The Ladies’ Home Journal snapped up a piece on the insanity of house-hunting and moving and titled it “Our Gingerbread Dream House” (November 1955). (One source claims the Journal didn’t pay her; instead it built the Dream House a breakfast room and butler’s pantry.) It was included, retitled “The Kerr-Hilton,” in Jean’s 1957 book, also titled Please Don’t Eat the Daisies.

If you know anything at all about Jean Kerr, if the name even rings a forlorn and forgotten synapse, you know that title and that House. Whatever the Kerrs paid for it they got back like an early investment in Apple stock. (A few years ago the house was listed for $5.495 million.)

The House needed capitalization. No ordinary suburban box, the House in tony Larchmont looking out at Long Island Sound, had been the coach house and stables for the 45,000 sq. ft. mansion built in 1901 for E. G. Crocker, the founder of Southern Pacific Railroad (later turned into a country club). Somehow Jean lived a life that sounded like fiction. While the Kerrs were negotiating to get the price down, part of the stables fortuitously caught fire, taking the impossible price tag with them. What was left still measured 8900 sq. ft. and formed three sides around a courtyard.

Four children did not fill it. It would have served as the embassy for a medium-sized country. The Addams Family would have been perfectly at home. (Modern pictures at this site.)

Full of once treasured stuff – the owner between them and Crocker, wealthy from being a Detroit auto pioneer, “cleverly acquired 35 truckloads of decor from the Vanderbilt mansion in Midtown Manhattan when it was being demolished” – the House needed to be all but gutted, and completely modern furnishings supplied. I remember the tens of thousands of dollars my modest, well-kept-up home nonetheless required when I moved in; my mind boggles at having to redo a mansion. The Kerrs certainly weren’t rich rich, but they were several levels up from the average reader. Jean left many hints that she was not average. Her kids went to a private school and she shopped at Saks Fifth Avenue. Nobody cared. Erma Bombeck and Joan Rivers also played the same tunes when they grew more fabulously wealthy than they were when they started. A persona is never reality.

Although half the essays applied to Everywoman, Daisies includes such outliers as a parody of Mickey Spillane done as a dramatic staged reading of Stephen Vincent Benét’s John Brown’s Body. (It was in fact read dramatically onstage by Orson Bean as a skit in the musical revue John Murray Anderson’s Almanac in 1953. Another of her skits was a parody of Daphne Du Maurier titled “My Cousin Who?” that appears never to have been reprinted. A loss.)

Other non-family entries included her dual life as both a writer of plays and attender of many more as a critic’s wife and another parody, of the young but blasé French novelist Francoise Sagan. Jean had range and a hidden stiletto that hinted at greatness, although she seldom cared to wield it, to the dismay of some critics.

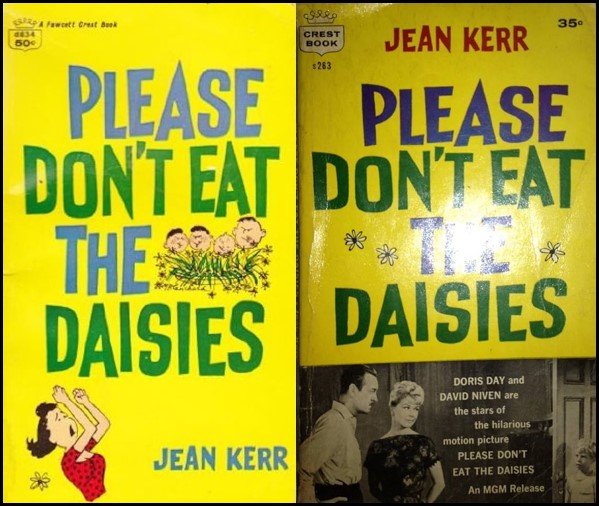

Received with rapturous reviews, the book spent 13 weeks at number one on the New York Times Best Sellers listings and stayed on the charts for a year. Time magazine later reported that it sold 275,000 in hardcover, and that seems low. Paperback reprints quickly followed, and may have sold in the millions. (Party pooper Walter didn’t produce a bestseller until 1962’s panegyric The Decline of Pleasure. Dinner conversations must have been interesting indeed.)

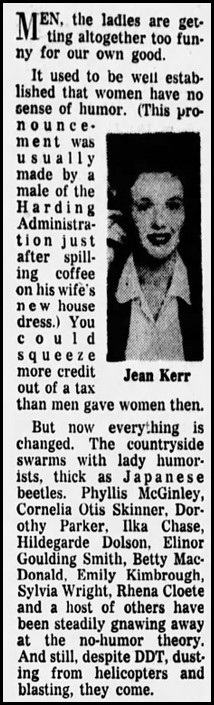

Even male critics were impressed. Under the headline “Women Can Be Funny Too,” Luthor Nichols of the San Francisco Examiner produced a tribute with as little condescension one was likely to find in the 1950s. (Pages on some of the women mentioned are forthcoming.)

Of course Hollywood bought a book that popular. And of course a book of humorous essays does not equal a movie. And of course that didn’t stop them. And of course I have no choice but to talk about something much less forgotten than the book.

That dratted movie

Please Don’t Eat the Daisies, the movie, appeared belatedly in 1960, probably because the writer, Isobel Lennart, a Hollywood veteran, had several nervous breakdowns trying to wrest a plot out of an essay. Or less. My cynical side insists that she never read the book but constructed the movie off a one-page list of bullet points. To be fair, she had virtually nothing to go on. Of the fifteen essays collected in the book, only that single one was on the House, only four on the children, and only mere passing mentions of Walter anywhere. Any good feminist writer therefore has meat for a dissertation on women’s value in the 1950s from the fact that the movie’s plot revolved around the Walter character.

Nevertheless, Doris Day, who played the Jean character, is always a ray of scrumptiously blonde sunshine in the oddly gloomy palette of the film. She serves as an exemplar of Hollywood glamorizing duller reality. The real-life Jean (“I’m a natural-born slob”) stood an awkward 5’11”, three inches taller than her husband, and, like most real-life mothers, complained about weight gain after each new child. Most of that was standard comedic self-deprecation, though, as a contemporary photo reveals.

Day, a superstar who would be the number one woman at the box office in 1960, remained at 38, the same age as Jean, the Hollywood ideal of housewife perfection. (Jean was a size 18 in contemporary terms; Day a size 6.) David Niven played her husband Larry. A suave college professor of drama whose one, very terrible, student play is twenty years behind him, he is forsaking academia for a job as theater critic. Will he retain his values when he becomes the toast of Broadway? That is not a plotline that resonates in modern times, and probably not even in 1960, but gives Day’s fight for his continued honesty the moral high ground that was assigned to “good” women in the period.

The skeletal plot requires any number of subplots to sustain the movie. The only one of concern here is the family’s move to their weird home in the suburbs.

There, the parade of workmen, the central casting cute children, Day’s mother, the maid, and a giant sheepdog standing in for the Kerrs’ wire terrier, make writing impossible. (A theme.) For Niven. Jean does not, in this movie, write. Niven moves to a swank hotel to write some chapters for his first book, as one does. Very relatable. Jean, Everywomen as Superwomen, seemingly overnight turns the broken-down, cluttered wreck of the House into a freshly-painted fully-furnished modern masterpiece – while also volunteering with the local theater group who are unknowingly putting on Niven’s failed play – so he can return home and work from his den. Mother – Day’s mother – knows best.

I’ll tell you what you are supposed to do. You pull yourself together, get this house in order, get on the phone, call Larry, tell him you miss him and you love him, and you want him to come home.

Telling women to give up their lives to ensure that their husbands can fulfill their desires may be the most perfect encapsulation of the fifties, but Jean had never lived a moment in that mode. No record of her opinion of the movie is findable, but it is easy to imagine.

The film was a top ten grosser in 1960. The paperback version of the book was re-released in 1962. A sitcom ran on ABC for two seasons starting in 1965. Walter was a respected critic – he would eventually win a Pulitzer Prize – back when a theater critic had the power to close a show. Jean was now a star.

Not that she needed the publicity, but The Snake Has All the Lines, fifteen more essays, appeared in 1960 as well. Five months on the NYT Best Sellers list; #1 on the Los Angeles Times’. Half the pieces were from the women’s magazines and the reader was constantly fed reminders that with the birth of Gregory in 1959 Jean now had five sons to deal with. Overall, though, the book was eclectic as the first with even another double parody, one using the Journal’s famous “Can This Marriage Be Saved” format with the combatants Vladimir Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert and Lolita. It did not appear in the Journal: the magazine would never have run such a piece even if Jean offered to give back the butler’s pantry. Only men’s magazines would have dared in that period. Esquire won the toss.

Mostly, though, Jean relied on that venerable staple of humorists, complaining about everyday annoyances humorously. Forgotten Humorist George Ade made complaints, albeit about personality types, the heart of his hundreds of fables, Stephen Leacock and Robert Benchley created personas of the befuddled man buffeted by life, S. J. Perelman twisted the complaints into dada. Benchley was the predecessor Jean was most often compared to, usually in encomiums like “the funniest humorist since Benchley.” Good company. Stand-ups by the thousands have mined the complaint vein for a century; Jerry Seinfeld is billionaireless without those jokes. Jean could find material in a day at the beach, buying a car, or, simply, men.

Just at the very moment when any good writer would have fate step in and change things, fate stepped in and changed things. No, not the surprise that her sixth child was a girl she named Katherine and called Kitty. Kitty didn’t enter the Kerrs’ lives until 1963. In 1961, Jean got … more famous, more honored, and much, much richer.

“Mary, Mary” opened on Broadway on March 9, 1961. P. G. Wodehouse, interviewed for the Paris Review, said, “I’ll tell you who is awfully good is Jean Kerr. Ooooh, she’s wonderful. Mary, Mary was one of the best plays I’ve ever read.” The syndicated columnist Wade Morehouse predicted that “It will probably strike gold in 46th St. and in a couple of years Miss Kerr may buy the New Haven Railroad.” Take that E. G. Crocker. The play overshadowed mere bestsellers. Audiences stayed with it for 1572 performances, the longest-running non-musical of the sixties. Yes, of course there was a romance between a younger woman and older man. Hollywood may have thought it would run forever because somebody from Warner Bros. showed up with gold, or at least moneybags, almost immediately, offering $500,000, and shot it in a hurry so that the film version was released in 1963, more than a year before the last Broadway performance.

Jean never reached those heights again and it’s not clear she even tried. Massive success may have taken away the constant drive. Her plays, with minimal casts and changes of scenery, were perfect for schools or local theaters and continually produced. Television and movie producers kept knocking on her door.

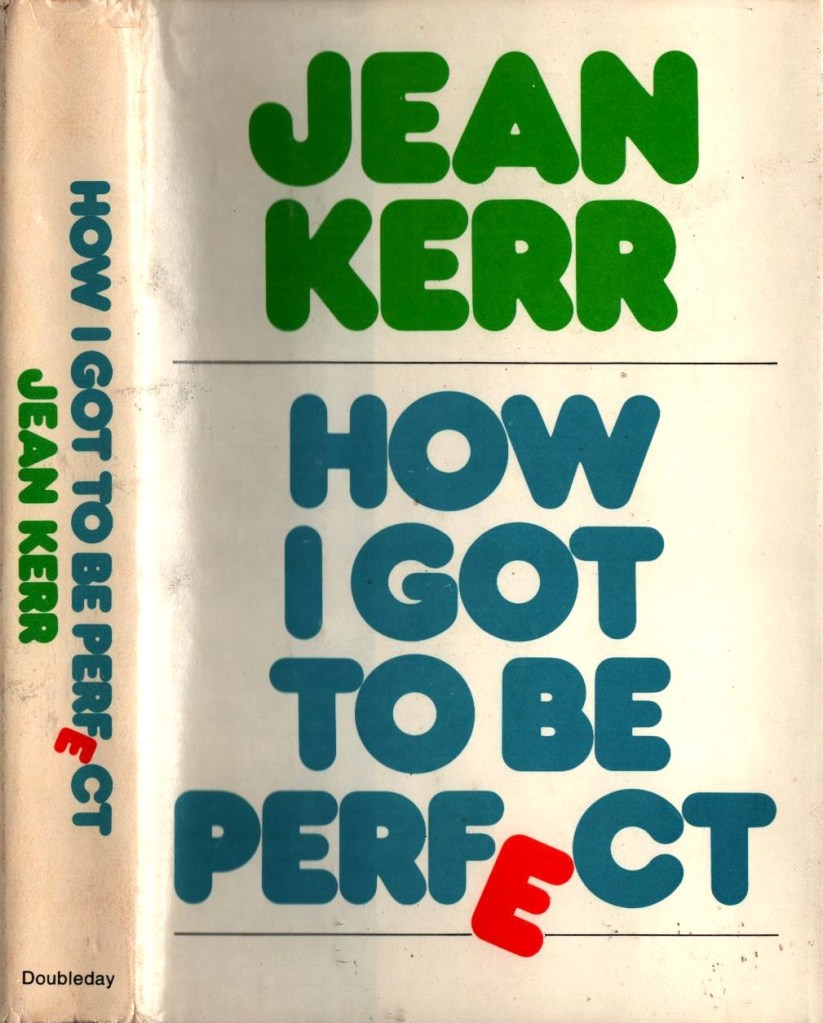

Although some darkness might be hidden in the last four decades of Jean’s life to explain her lack of productivity, that never reached print. Whatever the cause, Jean wrote less and relaxed her hectic fifties’ pace. Comic work dribbled out for another two decades. A few minor plays appeared to pleasant reviews. She released one more book of 15 essays in 1970, Penny Candy, and added a half dozen new pieces to her collection How I Got to be Perfect in 1979.

Aside 3: To be precise, the front flap proudly pronounces that “Six outrageous new essays by Jean Kerr” are to be found inside. However, the copyright page refers to only five. A meticulous check of the table of contents confirms that 39 of the 44 essays had been printed in her first three books. Was the publisher counting the “Introduction” as a new essay? In that case, why not also include the “Introduction to the Introduction”? Or was that too much whimsy even for a collection of humorous essays?

Jean stayed at Kerr-Hilton for 50 years, until she died in 2003, seven years after Walter. Virtually all the Forgotten Humorists I’ve written about belie the belief that comics must be bitter and sarcastic under the laughter. Possibly Will Cuppy was; the rest lived seemingly happy lives flitting from one high to another. Jean Kerr, perhaps, flew highest of them all.

Bibliography of Humorous Works

- 1957 – Please Don’t Eat the Daisies (Drawings by Carl Rose)

- 1960 – The Snake Has All the Lines (Illustrated by Whitney Darrow, Jr.)

- 1970 – Penny Candy (drawings by Whitney Darrow, Jr.)

- 1978 – How I Got to Be Perfect

You must be logged in to post a comment.