Every book tells a story, though not necessarily the one inside its pages. Some books, in fact, don’t have pages at all. Here’s their story.

My collection long ago grew larger than my memory. While exploring through the shelves recently I came across a book I’d forgotten I owned. The title provided no clue as to why I had it. So obviously the next move was to lift the cover and look inside. Surprise! The book was hollow, its pages carefully cut out, and a dumb gag was taped to the inside. Ridiculous. I don’t have cheap gags in my collection, no joke books, or silly caption books, or quickie compilations of quotes, but this one stood out. I had to know more. One of the most fun things collectors can do is explore the nichiest of niches in their field. Gag books turn out to be a tiny niche in the gigantic world of hollow books.

No better example exists of the descent of books from rare and precious items that only a handful of humanity owned to a throwaway commodity that was routinely neglected, dog-eared, or used as a notepad than hollow books.

Who would want to ruin a perfectly good, even if outdated, book by cutting out hundreds of pages to create a hole revealed only when the cover was opened? Virtually everybody, it seems, even today as any Google search will show.

When shelves of books by hundreds became a commonplace, the idea of hiding valuables inside one particular book occurred to everyone everywhere time after time. The Clements Library at the University of Michigan has one dating back to 1722: Historie ecclesiastique par Monsieur l’Abbe Fleury, volume 1 of 20. Their website condenses the history of hollow books nicely.

Such book boxes, also known as “book safes,” have a long history of use. They have been used to hide valuables from theft, smuggle weapons, drugs, and other contraband, and camouflage recording equipment and explosive devices. When backgammon was banned in England during the time of Henry VIII and all backgammon boards were ordered to be burned, people crafted them inside hollow books to conceal them. Hollow books were used during Prohibition to smuggle bottles of alcohol. Hiding an object in a book is also a popular plot device in fiction and film, including the movies From Russia with Love, The Shawshank Redemption, and The Matrix.

Serious uses always get transmogrified to comical ones. The serious types always get annoyed, none more splenetically than Holbrook Johnson in 1930.

And what of those who encourage this ghoulish trade? They are no better than body-snatchers, desecrators of the temple, vain, tawdry, callous, whether sellers of such monuments of destruction or buyers of them, biblioclasts and dolts to boot, necrophils of a sort…”

Imagine what an English bibliophile like Johnson would say if he ever came across Irving Fishlove. Fishlove ran the family company, H. Fishlove & Co. If you’re thinking that Fishlove can’t be a real name, cast yourself back to the early 20th Century, when Haim Fishelov came to America and changed his name. He and his then 16-year-old son founded the company in 1914; Irving took over when his father died a decade later. H. Fishlove & Co. made gag gifts and novelty items that told sold mostly to wholesalers who pushed them on the public.

Lisa Hix did two articles for Collectors Weekly – How Your Grandpa Got His LOLs and Fun Delivered: World’s Foremost Experts on Whoopee Cushions and Silly Putty Tell All – that provide the background on Irving’s gag empire courtesy of collecting couple Stan and Mardi Timm. They have a houseful of items: “Spectaculars (giant eyeglasses), chattering teeth, Whoops! plastic barf, girlie glasses, toilet-themed gag boxes, and Tricky Dogs (romantic-couple dog figurines with little magnets in their noses.”

Note those “toilet-themed gag boxes.” Irving Fishlove loved bathroom humor. “I think my dad had toilets on the brain,” said his son, who inherited the company. Americans loved bathroom humor. That love of bathroom humor sold a million copies of Forgotten Humorist Chic Sales‘ The Specialist in 1929 and probably sold a million bathroom gags for H. Fishlove & Co. over the years.

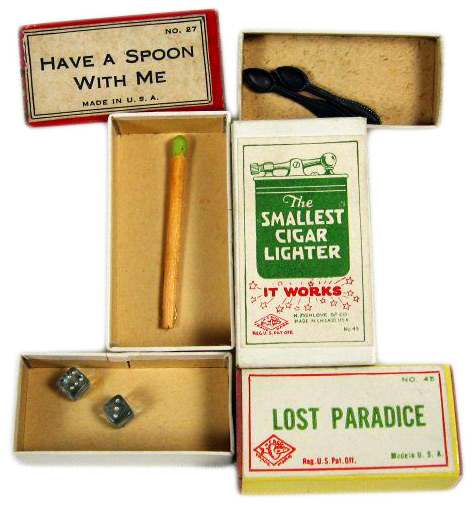

Gag boxes were the logical descendant of funny greeting cards, only in 3-D. What the front of the box said it contained was merely a lure; when opened the recipient saw that while the claim was literally accurate the interior was wholly unexpected. Gag boxes preceded the Fishloves but Irving pounced on the idea, especially after 1924, when TootsieToy started making injection-molded plastic toilets for dollhouses. Here’s a more modern example that shows off the concept perfectly.

Think about it. Once Fishlove bought a warehouse of tiny toilets he could use them for a thousand different punchlines. If he ran out of toilets, he substituted tiny chamber pots, tiny shovels, or tiny brooms.

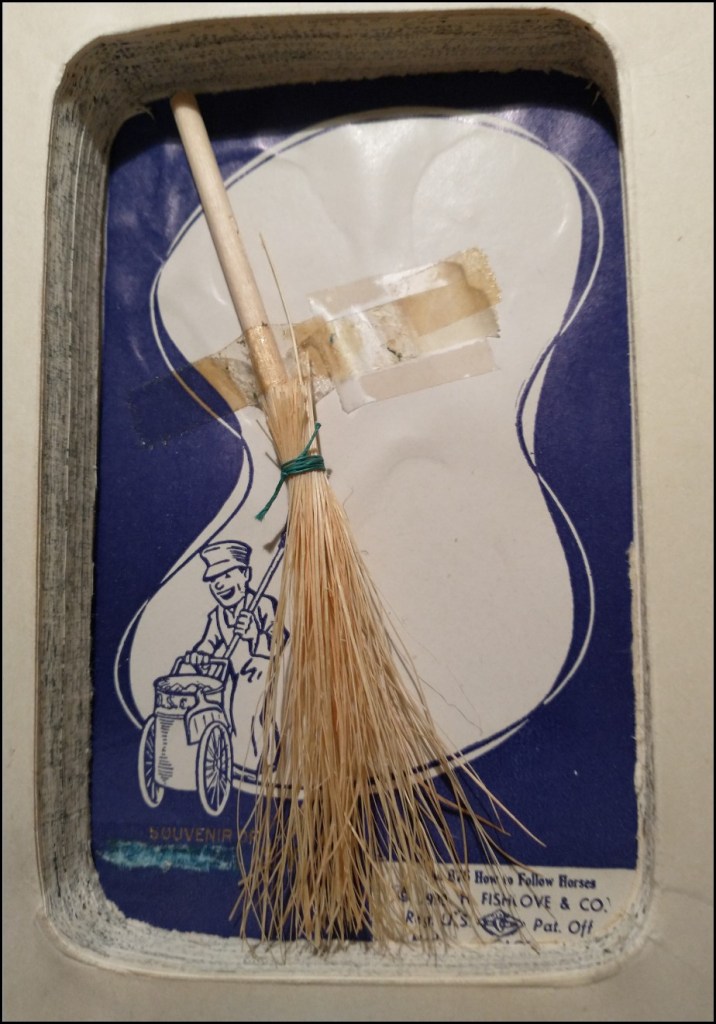

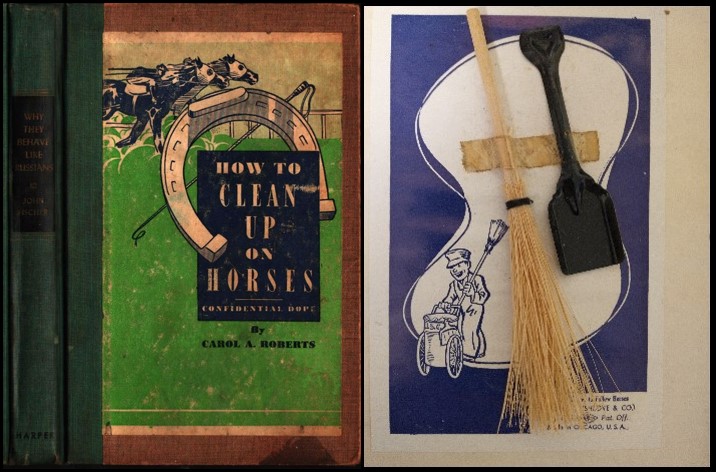

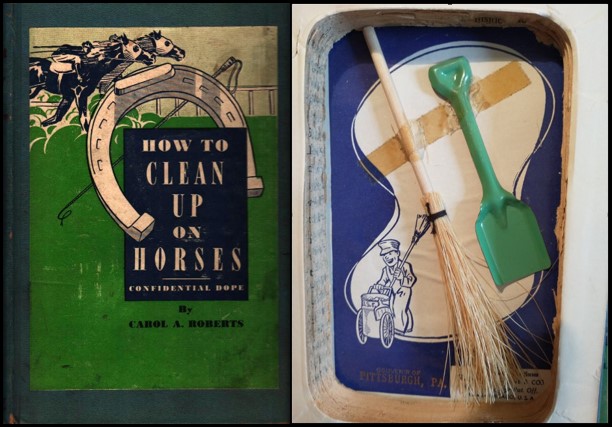

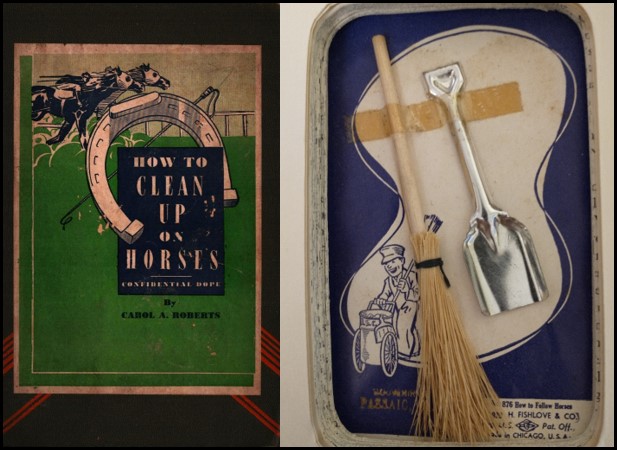

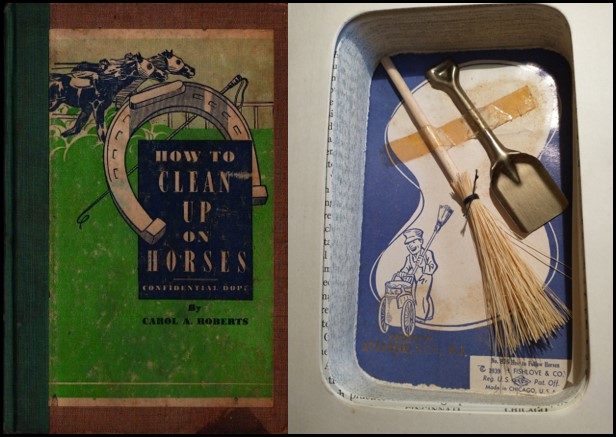

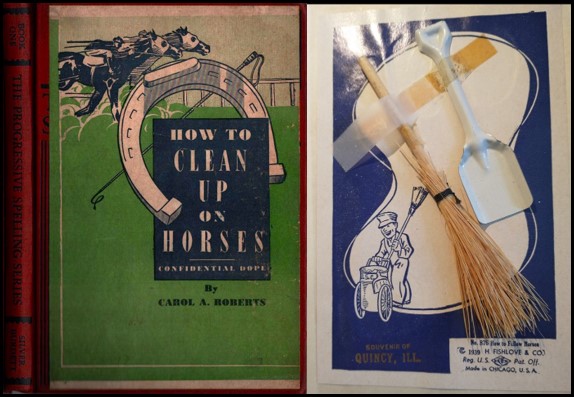

How to Clean Up on Horses (Clean Up) started me down the fragrant pathway that was Fishlove’s ziz-zag to hollow books. Warning: every example I first found made the gag poop, farts, or underwear.

Hollow books are one-piece gag boxes. The cover title promised one thing; the interior contained another. One-piece items are easier to stock and easier to handle by the recipient. Instead of prying open a close-fitting box cover, they could merely flip the cover. That made the gag easier to pass around to friends, say, at a party.

Books, moreover, are sadly unattractive past their prime times. Getting rid of a mass of books is a chore; you practically had to pay people to take them off your hands. In bulk, remaindered books cost virtually nothing. True, there is a cost to hollow out the books by cutting the middle cleanly out of all the pages. However, a worker with a band saw could probably create a sizable inventory of hollowed out books in a day.

Knowing no better I automatically shelved Clean Up under R for the pseudonymous Carol A. Roberts who, for some reason, probably an in-joke, is credited with the book. The spine told a different story. It read How to Be Poor by Frank Fay. I have that book!, I thought. Frank Fay was once a world-famous vaudeville comedian.

Aside: Kliph Nesteroff, who has built a reputation as the leading historian of stand-up, gave Fay enormous importance when he flatly stated that “Frank Fay is considered the very first stand-up comedian.” He influenced everybody who came of age between World Wars I and II. And yet, the webpage I just quoted is titled The Fascist Stand-Up Comic. Fay was perhaps the worst personality in comedy history, as sweeping a claim as that might be. Historians and collectors have to recognize that the past was often ugly. Many of the “gags” that H. Fishlove released were as stereotyped as the world a century ago, which the Timms’ collection reflects. To quote Mardi Timm, “You can’t understand history unless you look at it in its entirety, and then make decisions about what was right and what was wrong. You can’t just put it away like it doesn’t exist. Otherwise, how can you stop it from happening again?”

Here are the two books. Fishman just glued a piece of paper on the seemingly bare red Fay cover.

Actually, a very close look at the scan reveals that the original Fay cover has a gag of its own. Embossed into it is a caricature of Fay reduced to such poverty that he’s reduced to wearing a barrel in place of clothing, an old joke about the poor that suddenly became all too relevant during the Depression.

Fishman’s title makes Clean Up seem like a standard tout book on winning bets at the horse track. Racing, like boxing, was a stand-out sport in the first half of the 20th Century, though mostly neglected today. (Chico’s role as a tout selling Groucho multiple books on a sure-fire system to beat the horses is central to the plot of A Day at the Races, e.g.) Anyone opening the cover of that particular example to see the “Confidential Dope” would instead find only this.

Aha. The gag. Not “Clean Up” as in “Slang. a very large profit,” but clean up literally, as in “make someone or something clean or neat”. But the gag didn’t work. A broom? Pardon my French, but a broom wouldn’t clean up horseshit. Something was missing, obviously once in the blank area that also had tape.

I went online to find another copy. Naively I expected it to be a repeat of the Frank Fay book. Not at all. I saw descriptions like this one: “took a real book, in this case Nature Study and Health Education (McKnight & McKnight, Normal, Ill.) and precisely cut the heart out of the text block in the form of a vertical triangle with round corners.” I bought one of the many and received this.

The spine is hard to make out from the scan, but it reads Why They Behave Like Russians, by John Fischer. The cover is the same paste-down but the interior is much nicer. The gag is revealed: a shovel as well as a broom for clean up. But two things caught my eye. In the left-hand corner of the Fay interior is “SOUVENIR OF [something that is scratched out] N.Y.” Nothing at all is printed on the Fischer interior. And both books had a 1939 copyright, but the Fay book came in in 1946 and the Fischer book in 1947. Both of these much have fallen into Fishlove’s hands much later, maybe even in the 1950s.

A maniac Fishlove collector could probably spend years tracking down all the variants the company issued. I know of ten, all using different books as props. The earliest books were school readers from the 1920s, sure candidates for extermination, the later ones regular trade editions of titles that seemingly never sold well. The brooms stayed the same from beginning to end but the shovels varied in color. In addition to the black one above, I’ve seen green, silver, gray, white, and red versions, although I don’t have them all.

Move of them are labeled “Souvenir of” somewhere. Atlantic City was an obvious place to sell gag gifts, and one of the earliest did have that tourist town printed on the label. But others are from a spectrum of unlikely places, from prosaic Passaic, NJ to Pittsburgh, PA to Gary, IN to Quincy, IL, not exactly a major tourist attraction a century ago. Clearly Fishlove as the originator would take orders for a shipment of books, run the stickers through the printer one more time, and assemble new variants from whatever stock he had in the warehouse before sending the bundle out.

The sticker also made the claim that the gag was “Reg U.S. Pat. Off.” A basic search of the patent records finds no claim from Fishlove in 1939. Nor do I see anything patentable. Hollow books had been around for centuries. The items were obviously manually inserted and held in place by a piece of tape. Maybe the method of cutting the hole was new.

A really sharp eye will notice another oddity. All the interiors are labeled “No. 876 How to Follow Horses.” Why the actual title isn’t used is a mystery. Maybe they decided to change the name at the last minute. How to Follow Horses is another technically accurate description of the pictured man with the waste can and the broom but doesn’t have the ooomph of imagining cleaning up moneywise at the track.

Clean Up is easy to find online and it was issued for over a decade. That’s not bestseller territory, although the logical conclusion is that the gag was a steady seller.

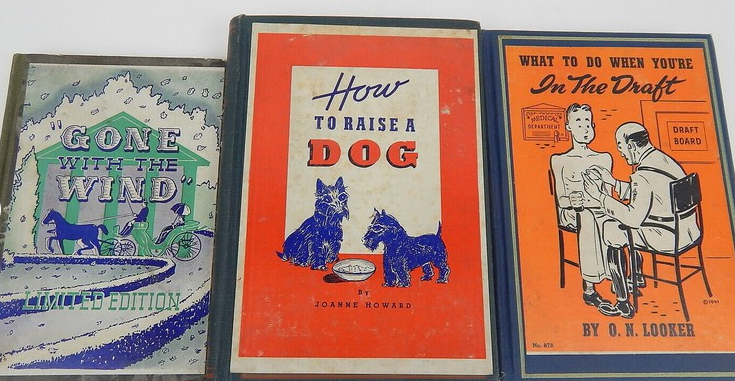

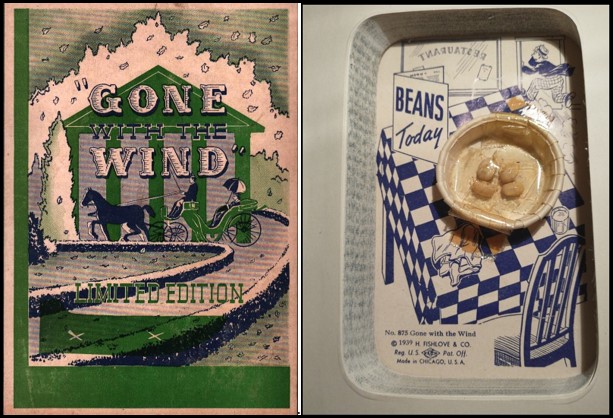

Another conclusion is that when a merchant finds something that is a steady seller, they make similar items that they hope will also sell. Fishlove saw a market niche. He created not just one hollow book but many. Presenting Gone with the Wind (Wind).

Sorry, that’s another bathroom humor joke, playing on the propensity of beans to make you toot. The timing is far more interesting. Gone with the Wind was the smash hit giant movie of 1939. At the bottom of the tablecloth is Fishlove’s info, “No. 875 Gone with the Wind/©1939”. My hunch is that Fishlove rushed this gag out to ride on the movie’s fame, even putting “Limited Edition” on the cover to get people to buy right away before another flood of movies swamped its familiarity. No author is mentioned anywhere, but apparently the title remained potent enough for a much later reprinting.

If Wind came first, then the sales encouraged Fishlove to try another hollow book with Clean Up, No. 876 following No. 875, assuming Fishlove used a rational numbering system. Dating the Winds is difficult. One copy is a small volume with the tell-tale spine completely bare, either a decision by the original publisher or sheer wear. The inside pages reveal that it’s a copy of the 1919 publication of the long dead Emily Nonnen’s novel The Stork’s Necklace. (The container of beans was torn away. Collecting hollow books in good condition with the gags intact is a challenge.) The other much larger book is a anthology of stories and articles from 1942, R. N. Cohen’s Flying High, part of the Air-Age Education Series.

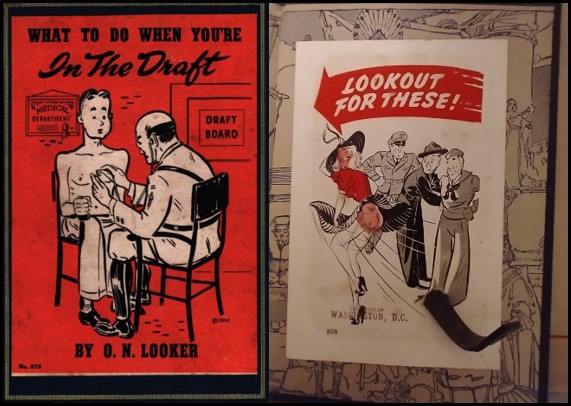

Fishlove’s lasting gag is on bibliographers trying to apply a seemingly straightforward method to his madness. I came close when I found No. 878, What to Do When You’re In the Draft. (That cover is orange; for some reason my scanner insists upon red and no adjustments later bring out the true color.)

Gag boxes were a huge hit during World War II. Soldiers loved them and they were easy to send overseas, as the Timms explained.

Mardi: Apparently, Fishlove was trying to find out why his gag boxes held a priority with the mail service during World War II. Why did his stuff go to the troops, when other stuff didn’t? So in Washington, he asked the U.S. Postal Service, and they said, “We’ve had combat fatigue cases that never cracked a smile for weeks until somebody handed them a gag.” Ain’t that neat? So Fishlove gags were incredibly important for the war effort.

Stan: Yes. There were about three or four gags they emphasized for the troops, and they did them with the toilets again.

Mardi: At the time, there was a draft. And so one showed a soldier on the outside saying, “If You Gotta Go, You Gotta Go …,” the idea being that you’re being drafted. And you open it up and there would be a miniature toilet in it.

Stan: People also sent soldiers a lot of girlie-type boxes which contained an unclad young lady or tiny cloth panties inside.

In the Draft is a prime example of a girlie-type. Opening the cover revealed the sticker on the back. The art depicts three servicemen staring at a beautiful woman with bare legs whose behind is covered by a movable strip of rubber. The temptation to pivot the rubber, which sounds slightly dirty right there, revealed the woman’s pink panties, her skirt being raised because – get this – she’s caught in a draft. The purported author is O. N. Looker, a neat pun when you learn the truth. My copy is printed “Souvenir of Washington, D. C., but has none of the other info. Nevertheless, at the bottom left of the front cover is a definite No. 878 and there is another 878 discretely on the back sticker. Although the gag certainly was issued during the war, my copy is of a schoolbook published in 1919, a refugee, perhaps, from a paper drive.

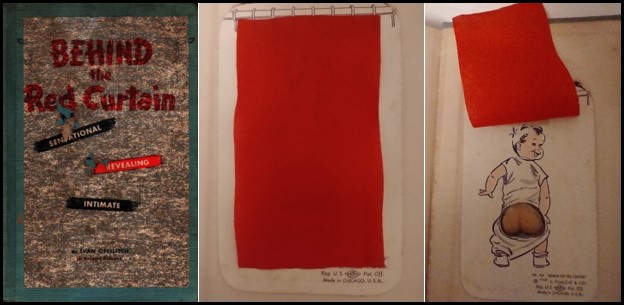

Those with neat and tidy souls would prefer my next volume to be No. 877, or at least to be something near that. Not in a Fishlove world. The only other hollow book with a number I’ve found is copyright 1948. To bibliographic consternation, the book’s number is 614. even though by that time catalog numbers should be much higher. (He could have started over again, a dismaying idea.)

The joke is a timely one, because by then the Cold War had started and Red Russia was the subject of hysterical denunciation. Winston Churchill had given a speech in which he declared that Eastern European countries were trapped behind an iron curtain. What was going on there? The answer purported to lie in Behind the Red Curtain by “Escaped Refugee” Ivan Offilitch. Lifting the cover revealed only an elaborate gag that, as with In the Draft, also required the reader’s interaction.

“Sensational. Revealing. Intimate.” reads the cover. Not very, unless you get the joke that the toddler’s three-dimensional bottom is likely a pair of breasts stolen from some other girlie gag.

My copy is of a quickly obsoleted wartime volume, Charles Kenneth Arey’s Elementary School Science for the Air Age, A Teachers’ Guide, 1942. Elementary in this case means basic rather than a book for grammar schoolers. A few words left uncut tells us that the book was part of the Air-Age Education Series put out by the Aviation Education Research Group, containing the “Science of Pre-Flight Aeronautics for High Schools.” Few remnants of the period of total war reminds us more thoroughly and instantly of how desperately afraid for the future the country was in that first full war year.

Observant readers might have noticed that the R. N. Cohen book used for Gone with the Wind also was part of the Air-Age Education Series. Could Fishlove have waited until 1948 to release it after buying up a pallet of unsold Air-Age readers? A tantalizing thought that would give weight to the lasting appeal of hollow book gags. And would give some sensible overarching system to Fishlove’s production schedules.

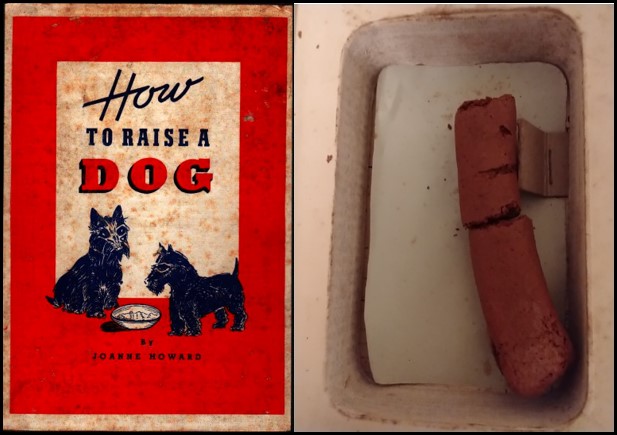

Sadly for my sanity I discovered one more gag hollow book, and it confounds all logic. The book is so obviously a Fishlove product that it practically calls out Irving’s name. Yet there is no number. Worse, no identification can be found on the inside. No sticker, no copyright notice, no patent information, no address, no company name, no “Souvenir of.” And, to twist the dagger, the gag is not related to behinds in any way.

That hideous object on the right is supposed to be a frankfurter, aka wiener, aka hot dog. You “raise a dog” by lifting the sausage to your mouth. True, that sounds more salacious than revealing a baby’s bare bottom but as a joke it’s at best a weenie.

Dating the volume is impossible. The dogs on the cover look like Asta, real name Skippy, the wire fox Terrier who had starred in The Thin Man and more than a dozen other movies, many huge hits, in the 1930s. He also reappeared in After the Thin Man in 1936 and Another Thin Man, which was released in 1939. That’s the same year as Gone with the Wind and the same year that saw Fishlove’s first known copyright of a hollow book gag. Was this Dog a test to gauge the market in 1939? My copy is hollowed from a 1920s school reader series, so it could have appeared earlier or later than Gone with the Wind. For Fishlove gags were an everyday and everyyear concern.

The hollow books seem to fade out by the mid-1950s, although more titles might be found at any time. Fishlove thrived in that decade, gag gifts going from a gentleman’s snigger to a universal – usually clean – jokes for all ages. Chattering Teeth and the fake vomit sold as “Whoops!” are both creatures that appeared in catalogs marketed to adults and ads in comic books in the 1950s. Toilet jokes faded away, according to the Timms, because of the decade’s conservatism. Yet the industry, always aimed at men and boys, now served up a dubious step toward gender equality, with products aimed at women like the spoons with holes in them marketed as diet aids.

Hollow books are an equally dubious niche for book collectors. Yet humor always tells us something about the time it was produced. Each decade has its own form of taboos. Movies were severely censored after the Hayes Act finally started being enforced in 1934. Some think that the restrictions improved the films as writers needed to cleverly imply rather than show anything formally banned. A vast underworld of “men’s” products emerged to produce slightly smutty material just outside of the mainstream. Bathroom humor was taboo; although tiny toilets were allowed in dollhouses, working toilets didn’t make their appearance in Hollywood films until the 1960s. Paradoxically, bathroom humor was cleaner – that word again – than depictions of sex or nudity, which were strictly under the counter stuff – except when soldiers were involved.

How could bathroom humor compete? It took a while but comedy embraced it in the 21st century, especially in movies no longer subject to bans. The 2020s has its own set of taboos, of course. Every decade stirs up its own brand of outrage that will seem ludicrous to future historians. Taboos are therefore vital to examine. And so are taboo breakers, from high art to the lowest of the low.

You must be logged in to post a comment.