Somebody has to be the youngest at a party. In the soon-to-be-immortal world of the Algonquin Group and The New Yorker, it was Corey H. Ford.

Ford, like so many others of that crowd, was the editor of his college humor magazine, the Columbia Jester. There he published a series of parodies of the Rover Boys. OK, that doesn’t strike many bells today, but they were a million-selling smash in the early 20th Century, the peak of the boy’s books crowd that included the Hardy Boys, the Bobbsey Twins, Tom Swift, and Nancy Drew, all created by Edward L. Stratemeyer. (And the ludicrously-named Strenuous Lad’s Library, written by Forgotten Humorist George Ade in an off moment.) The earnest, clean-cut, and oh-so-perfect Tom, Dick, and… Sam were ripe for parody. Ford soon got hired by the two leading humor magazines of the day, Judge and Life, and continued the parodies in the latter. Stratemeyer had exactly as much of a sense of humor as you might expect and threatened suit. Dumb move. Ford just changed the name of his victims to the Rollo Boys and collected all the parodies in a 1925 book Three Rousing Cheers for the Rollo Boys, launching his career. The book made his name, or someone’s name, as the Atlanta Constitution was slow to catch on.

Wonderfully for us, the book was illustrated by Gluyas Williams, later to be a staple of the early New Yorker and the illustrator of almost all of Robert Benchley’s books. In one of the parodies, the Rollo Boys meet America’s top humorists. That’s them below. The tall man in white is Forgotten Humorist Donald Ogden Stewart. The man with the cigar is Irvin Cobb, himself a Forgotten Humorist. Going further counterclockwise we see caricatures of humorists that mostly still ring bells: playwrights Marc Connelly and George S. Kaufman, Canadian superstar Stephen Leacock, columnist Heywood Broun, the back of the apparently instantly recognizable Dorothy Parker, Will Rogers, Ring Lardner, “and on the floor, studying a newt, Robert Benchley.”

Aside 1: If you don’t know that Benchley’s breakthrough was a piece called “The Social Life of a Newt,” stop here and go read it, seeing that it’s easily findable in text form online since it is well out of copyright.

OK, welcome back. The old Life magazine, thoroughly forgotten today, did a series of articles and even whole issues that were parodies of other magazines, another idea it stole from college humor mags. Ford was useful in these. The humor crowd was a small incestuous family; they supported one another even as they sniped and quarreled. Any one or any several of them would show up in the projects of other. Here’s Dorothy’s Parker front, along with a rare picture of Harpo Marx pulling a “Gookie” in street clothes, from Life’s “News Stand” issue.

The New Yorker is so iconic today that many of its featured writers are inevitably tagged New Yorker writers. Conveniently passed over is the embarrassing fact that most of the big names in the 1920s thought that the magazine was sure to fail and so didn’t want to be associated with it. Even to a humor historian the first issue, February 21, 1925, is remembered for absolutely nothing except the Rea Irvin cover of a top-hatted fop looking at a butterfly through a monocle, which became the magazine’s endlessly caricatured trademark. The contributors mostly hide behind pseudonyms. One such bit of satire is signed Etaoin Shrdlu, an insider joke taken from the most-frequently used letters of the alphabet. Shrdlu shares the page with one Corey Ford.

Aside 2: A magnificent article on Irvin and Tilley by R. J. Harvey appeared in The Comics Journal), a must-read for humor buffs.

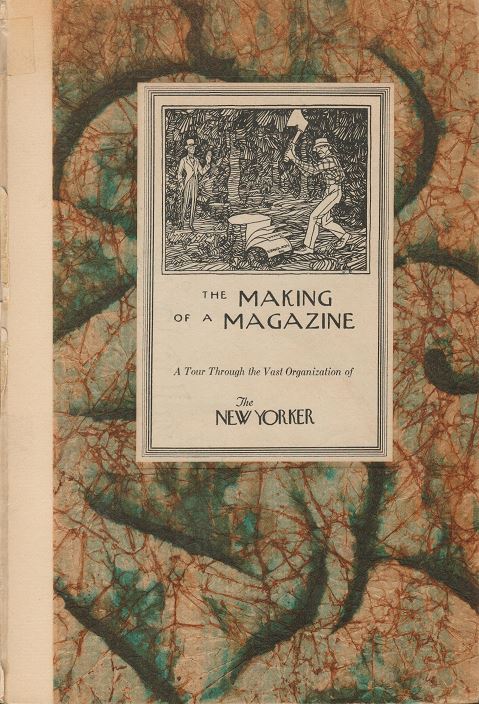

Ford was probably the most prolific New Yorker writer that first year, contributing a 21-issue series called The Making of a Magazine, a series of spoofs on publishing, with suitably old-fashioned woodblock illustrations by Johan Bull. Ford used the fop as a character, giving him in the process, his immortal name, Eustace Tilley. Ninety-eight years later, these virtually unseen pages are now in the public domain. A sampling.

And the last installment, the first to mention the author’s name.

The New Yorker thought enough of this work to bind the chapters into hardcovers and release it to promote the magazine. No date, no copyright, and no mention of an author can be found in it. It’s not found in any standard listing of Ford’s books. This little oddity must be among the scarcest books of any of the Forgotten Humorists on this site and among the scarcest New Yorker associational titles ever released.

Even odder is the fact that the publication deliberately left out one of the chapters, although the contents provides a clue. Chapter XI, “The New Yorkerette,” is a parody of the early New Yorker itself, a page of old-fashioned gags, insider gossip, and pretentious name-dropping, the stuff that drove away advertisers by the score. You can read it here and understand why.

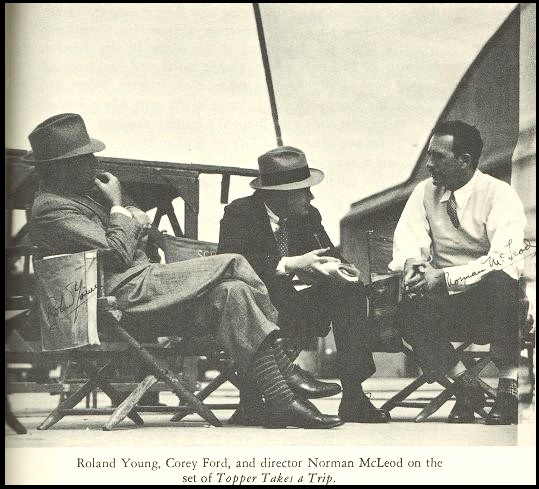

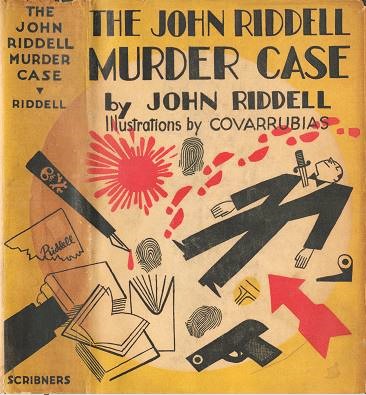

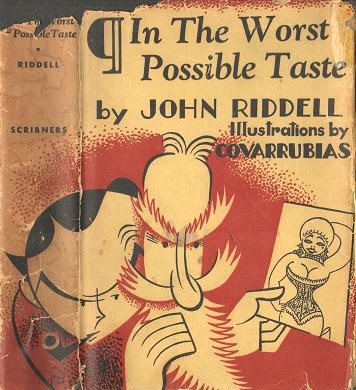

Ford isn’t a name associated with The New Yorker because he spent the rest of the decade reading every novel of importance, enabling him to fill three with parodies first published by its established and seemingly far more sophisticated rival, Vanity Fair. (Ford wrote these under the far funnier pseudonym of John Riddell, “a clever rearrangement of the letters of my own name,” he later wrote.) They were illustrated by Miguel Covarrubias, whose exceptional style can be seen at top with his caricature of Ford.

His biggest success was another novel-length parody. For those who think that bogus memoirs that are debunked as fictional are a modern invention, let me introduce Joan Lowell. In 1928 she released a much-ballyhooed memoir about her seventeen years as the only “woman-thing” on her father’s trading ship. Sales were spectacular, the Book-of-the-Month club made it a selection, and its authenticity was certified by genuine old salts. Until a touch of research showed that she had been a junior high student at the time she supposedly sailed the seas. In response, Ford churned out a somehow even more improbable tale titled Salt Water Taffy: or, Twenty thousand leagues away from the sea: the almost incredible autobiography of Capt. Ezra Triplett’s seafaring daughter. Released in May 1929, it went through seven printings by July and briefly hit number one on the bestsellers lists.

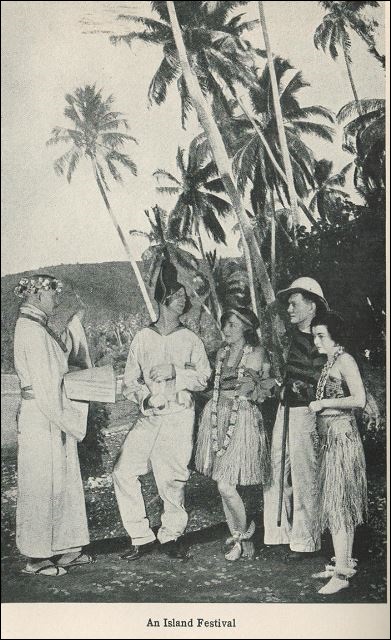

Another set of prank photos accompanied the prank text. The one below has, improbably enough itself, both the editor of Vanity Fair (Frank Crowninshield) on the left, and the editor of The New Yorker (Harold Ross) on the right. The man in the middle is Donald Ogden Stewart, popping up everywhere. The native girls flanking Ross are painter and Algonquin Group member Neysa McMein and novelist Elizabeth Cobb Chapman, the daughter of the already mentioned Irvin S. Cobb. They were all part of a club, and you were either in or out. But if you were in, you were golden. And therefore much resented by outsiders, possibly a reason why Ford walked away.

Another reason was that, much unlike the rest of the club, whose idea of a trek through the wilds was a walk through Central Park to a speakeasy, Ford was as much of an outdoorsman and world traveler as Ernest Hemingway (who much resented Ford’s parody of his style). His apartment (shared with Forgotten Humorist Frank Sullivan) was “decorated with a Dyak war shield and blowpipes and poisoned arrows which I had brought back after spending several months with the headhunters of central Dutch Borneo. (Consider that said very casually.)” He spent another summer “with the Eskimos along the Bering Sea.” Although he continued writing a few short humor pieces and was subsidized by miserable stays in Hollywood, he put away the hijinks. In the 1940s he wrote a series of books about the war while working with the Office of Strategic Services, which he thereupon wrote a history of when the war ended. He rose to be a colonel in the reserves.

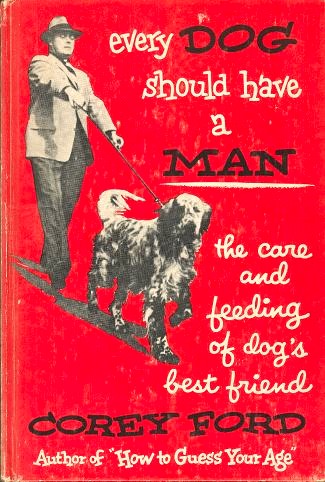

Post-war he became a columnist in Field and Stream. Two books full of humorous stories endeared him to all outdoorsmen, Minutes of the Lower Forty and Uncle Perk’s Jug, which followed Every Dog Should Have a Man and You Can Always Tell A Fisherman (but can’t tell him much).

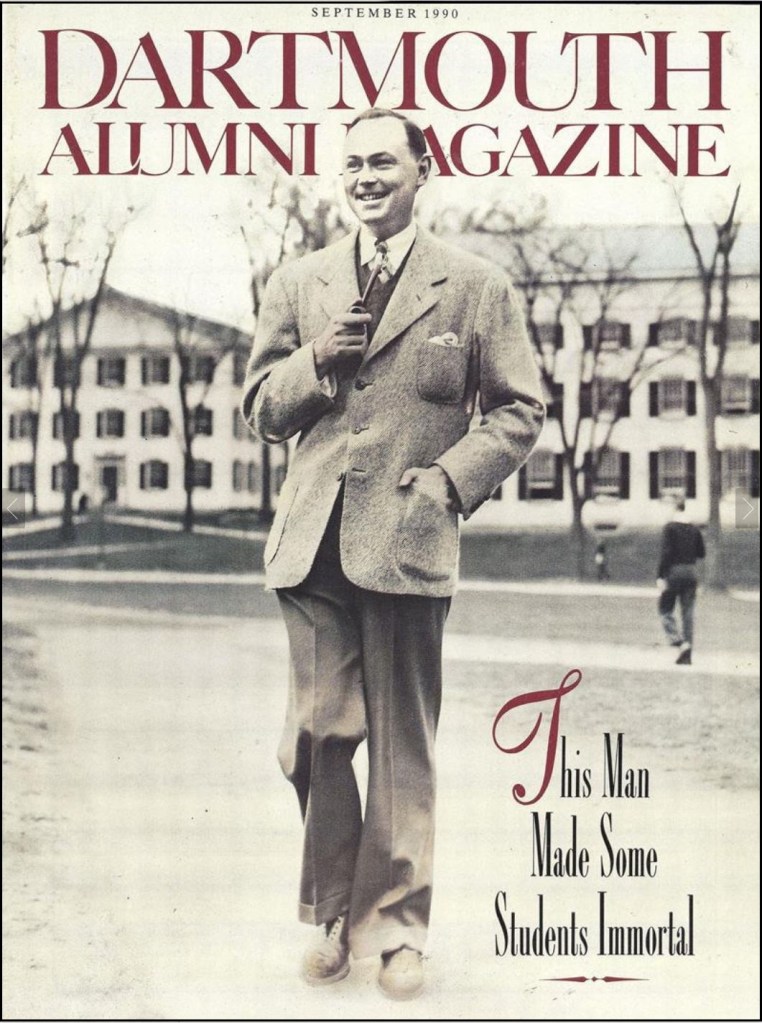

All those bestsellers apparently set him up for life. He left New York for the wilds of Dartmouth, NH. Semi-wilds, since that’s also the home of Dartmouth University, where he surprisingly became writer-in-residence. (Dartmouth in is Hanover and, disguised as Hardscabble, served as the home of the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club for his columns. The name was an homage to the Thanatopsis Pleasure and Inside Straight Club, the poker-playing buddies of the Algonquin crowd. Once you’re in, you never go out.

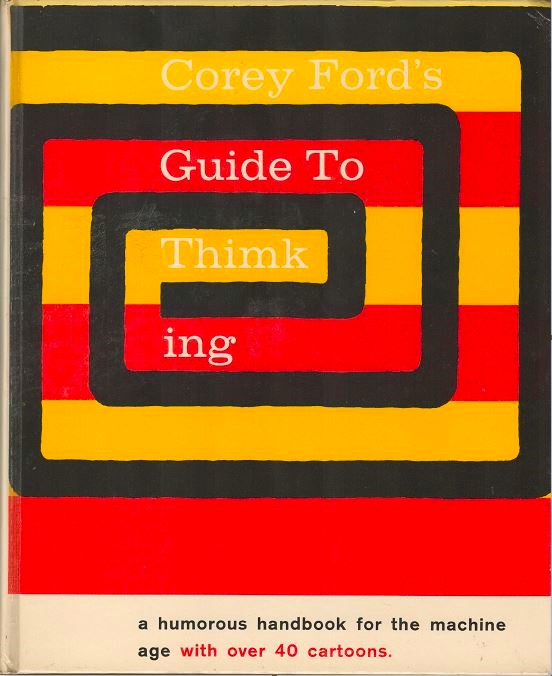

Another dozen or so short humor books dribbled out during the 1950s, from the endlessly plagiarized How to Guess Your Age to Corey Ford’s Guide to Thimking, one of the first humor books about computers, filled with vintage cartoons about giant electronic brains. Thimking is not a misprint, but a pun on IBM’s omnipresent motto, THINK.

His masterpiece didn’t appear until 1967, shortly before his death. The Time of Laughter is a combination memoir, history of Twenties humor, and anthology of snippits of almost lost works.

About 99% of what we know about Ford pre-WWII comes directly from the volume. My contribution is solely that his middle initial was “H”, a fact dug up from 1920s newspaper articles. What it stood for remains a secret. Laughter is a must-read for anyone wanting to dive into that magical decade, full of vintage photos and contemporary illustrations hard to find anywhere else. With odd modesty, the only picture of Ford in the book or on the dust jacket is one of him in the shadows and wearing a hat. He looks like a spy in a movie and reveals just as little about himself. Fitting for a man almost determined to be forgotten.

Bibliography of Humorous Works

- 1925 – The Making of a Magazine (name not credited; illustrated by Johan Bull)

- 1925 – Three Rousing Cheers for the Rollo Boys (illustrated by Gluyas WIlliams)

- 1926 – The Gazelle’s Ears (Illustrated by [Al] Freuh)

- 1928 – Meaning no Offense: Being Some of the Life, Adventures and Opinions of Trader Riddell, an Old Book Reviewer, in the Dark Continent of Contemporary Literature; including an Assortment of Strange Interviews and Literary Follies (as by John Riddell; Illustrated by [Miguel] Covarrubias)

- 1929 – Salt Water Taffy: or, Twenty Thousand Leagues Away from the Sea: the Almost Incredible Autobiography of Capt. Ezra Triplett’s Seafaring Daughter (photographs uncredited)

- 1930 – The John Riddell Murder Case : a Philo Vance Parody (as by John Riddell; illustrated by Miguel Covarrubias)

- 1931 – Coconut Oil: June Triplett’s Amazing Book Out of Darkest Africa! (photographs uncredited)

- 1931 – In the Worst Possible Taste (as by John Riddell; illustrated by Miguel Covarrubias)

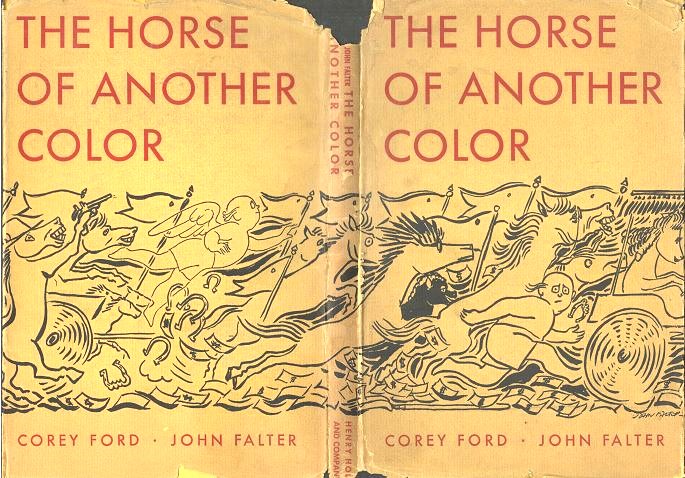

- 1946 – The Horse of Another Color (drawings by John Falter)

- 1950 – How To Guess Your Age (illustrated by Gluyas WIlliams)

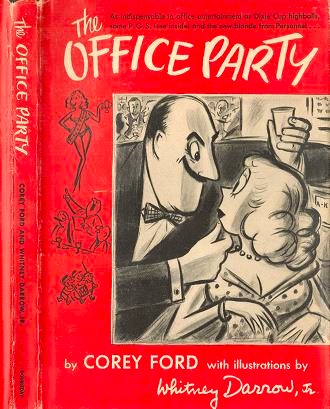

- 1951 – The Office Party (illustrated by Whitney Darrow, Jr.)

- 1952 – Every Dog Should Have A Man (photographs by Dan Holland)

- 1954 – Never Say Diet (illustrated by R[ichard]. Taylor)

- 1958 – Has Anybody Seen Me Lately? (illustrated by Whitney Darrow, Jr., R[ichard]. Taylor, and Gluyas WIlliams)

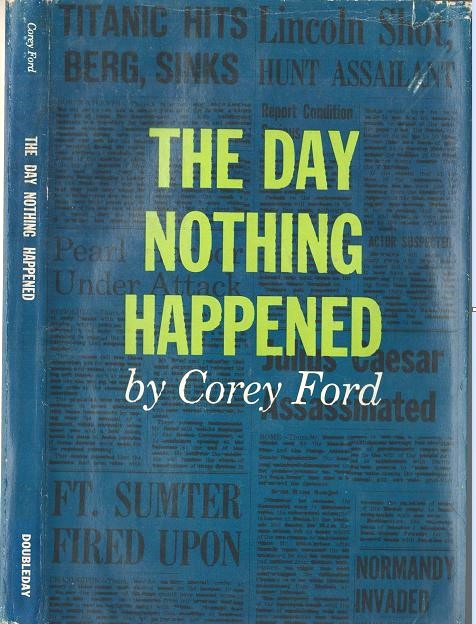

- 1959 – The Day Nothing Happened (photographs uncredited)

- 1961 – Corey Ford’s Guide to Thimking

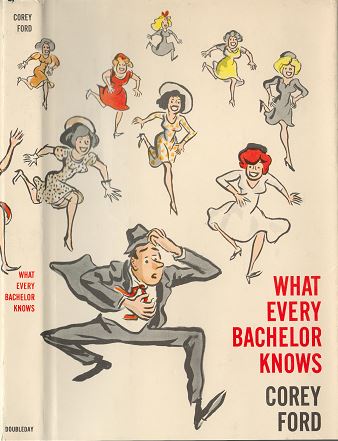

- 1961 – What Every Bachelor Knows (illustrated by Robert Day)

- 1964 – And How Do We Feel This Morning? (illustrated by Eric Gurney)

You must be logged in to post a comment.