Chic Sale is the wild outlier in this collection of humorists. True, like Robert Benchley he rose to fame from a comic monologue he delivered to audiences, but Benchley was a writer who accidentally became a performer and Sale was a performer who accidentally became a writer. His first try sold. And sold and sold and sold, through dozens of printings. It may be the bestselling book of humor of the 20th Century.

True to his future self, Charles Partlow “Chic” Sale, started his existence as an outlier. Sale is the only American humorist on these pages who wasn’t born in the United States. Yet, you can’t get much more American than being fathered by a frontier dentist in the just-settled railroad boom town of Huron in the Dakota Territory, four years before South Dakota became a state. Fun fact: Huron is now distinguished by a statue called the World’s Largest Pheasant.

Possibly not wanting to wait for the statue until 1959, Sale’s family soon moved to the literally more urbane precincts of Urbana, IL, home of the University of Illinois, which Sale would later claim to have attended. Nevertheless, the lad enjoyed a “Tom Sawyer” life, surrounded by rural characters whose foibles, escapades, and speech patterns he committed to memory and reenacted in lectures and vaudeville, from his teenage years to his early death. His act consisted of what then were called “agricultural types,” some teachers, some students, some old men telling stories about the glories of the Union Army. He soon made a name for himself: Chick Earle. The earliest newspaper story I’ve found shows Sale, a vaudeville veteran at the age of 23, slipping into the news on September 19, 1908, as “Chick Earle character impersonator, making twelve complete changes in wardrobe.” This was very far from the bright lights in the big city, out in Marion, OH. The featured act was Deblaker’s dog and monkey circus.

Only six months later, his schedule put him back in Urbana. A local paper welcomed his homecoming by recognizing him as good ol’ “Charley” Sale, son of Dr. and Mrs. F. O. Sale.

Sale always maintained that he never invented any of his many characters, but just took the people he knew and adapted them for the stage. Maybe something about being home convinced him that he needed to be himself instead of a made-up character. Whatever the reason, that appearance in Urbana is the last time newspapers record the vaudeville career of Chick Earle. Back in Ohio two months later, in May 1909, Chic Sale – “the impersonator” – makes the first of thousands of appearances in the news. Always swimming against the tide, Charley Sale must be the only actor who became a star after changing his stage name back to the one he was born with. His official onstage designation was always Charles “Chic” Sale, but gladly answered to just Chic, while Charley became Charlie.

Within a few years, he hit the top of the field, playing the Palace in New York. “Sale is an artist to his fingertips and he strives to make natural the types he portrays. None is overdone. He characterizes types that are familiar to most Americans with telling realism and humor,” said the New York Dramatic Mirror.

No wonder that he and the most famous rural character in American theater, Will Rogers, were close friends throughout their careers. They took different routes, with Rogers eventually satirizing modern society and Sale lampooning the disappearing small town. Both moved into longer-form humor but in their early careers both were what were called wisecrackers, a term that had just come into the language.

Aside No. 1: In fact, O. O. McIntyre, a widely syndicated New York newspaper columnist, claimed in his August 15, 1923 column that Sale coined the word “wisecrack.” Or maybe just was the first to use it on stage. In his May 2, 1926 column, McIntyre says Sale first heard it in front of a livery stable in the middle west. “One of the loafers pulled a pun. Another chortled and exclaimed, ‘There’s a wise crack for you’.” McIntyre loved Sale; he wrote the “Introduction” to Sale’s second book. Whenever he couldn’t think of a way to pad out his column, he included this factoid.

Here’s the problem. The first hit I find in the newspaper database is from an 1897 paper, in which a small town politician makes a “wise crack.” Although wisecracker has a sporting connection from 1912, wisecracking was at first associated with country wits, not city slickers. Will Rogers was already calling his humor wise cracks in 1919. In vaudeville, Si Jenks and Victoria Allen suddenly billed themselves “the small-town wise-crackers” as early as 1919. “Mr. Jenks is well known for his portrayal of ‘rube’ characters,” wrote the Champaign [IL] Daily News on September 9, 1919.

What was a wisecracker? This set of jokes was hopping from newspaper to newspaper in 1903.

Rural or “rube” or “hick” characters were plentiful in vaudeville. If “wisecracker” was the hot new slang of the day, then using the label might give a team an edge over the others. Maybe that worked for a while; unfortunately, mentions of Si Jenks and Victoria Allen disappear after 1923. Chic Sale goes on and on. He might or might not have brought the term onto the stage, but he had O. O. McIntyre – the equivalent of going viral today – and they didn’t.

By the end of the 1920s he was appearing on Broadway, considered a step up even from the peaks of vaudeville, joking that he was the only star in musical comedies who could neither sing or dance.

Where in all this biography is the print humorist who would sell millions? Where did Sale come up with a monolog that was so risque that he could only tell it to male audiences, although it was also so clean that not a single word could be censored? For in the radically different world before WWII, the mundane subject of building an outhouse was so forbidden that creating a “specialist” who designed them keeping in mind all the faults and foibles of the very human users who would inhabit them, however briefly, caused howls of laughter.

Buried in all those vaudeville performances is a seemingly meaningless chat Sale had one evening in the lobby of the Mecca Hotel in Denver. The year was 1912. Or so the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette would write in 1930. The truth is probably more complicated.

I do extensive research in newspaper databases before writing these pieces. Fortunately, several lengthy newspaper stories chronicled the history of how The Specialist got into print. Did they do extensive research or just write up a good yarn with uncheckable details? Spoiler: it’s the latter. Can they be checked? Amazingly, the answer is yes. Matthew Sale Brown, Chic’s youngest grandson, maintains a website on his grandfather. I approached him with bibliographic questions I couldn’t answer and he graciously offered more than I could have imagined. His grandmother, Marie Bishop Sale, wrote an unpublished biography of Chic, The Life of Charles “Chic” Sale, in 1981. (Compiled, indexed, and edited by Cherry Sale Brown.)

Marie Bishop was a young concert violinist who married Chic in 1912. They would have four children, occasionally tour together, and stay seemingly happily married until his death, another outlier in actor history.

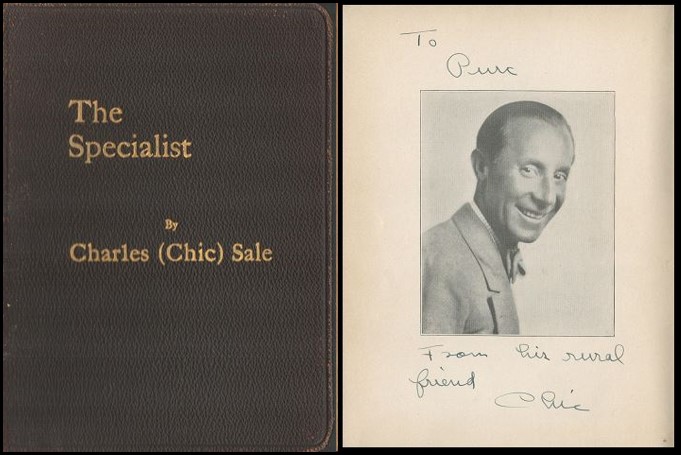

I’m adding a second photo not merely because it’s far more attractive but to note that the Boston Globe, a major newspaper, typoed Chic’s last name in this caption and in the article called him “Chick.” Extensive research indeed.

And it gets worse. There’s no evidence that Chic ever went to college. The closest may have been during visits home when Chic honed his chops at his brother’s frat house at the University of Illinois. Nevertheless the Globe confidently reports that Chic gave up college to go on the stage just two years earlier. Did they confuse Chic with his brother? Did he gave them a yarn to make him look better as a partner for a woman who “had been prominent in social affairs” in Seattle?

Saving me from the dire fate of having to reconcile contradictory newspaper articles, Matt sent me photos of the biography’s pages dealing with the publishing of The Specialist – the book that would be made of the outhouse building monolog and sell in the millions – with permission to use them to improve this article. The Life will be my primary source. Newspaper articles will be used as backup for other material and to give you readers an idea of what the public learned about Sale at the peak of his astounding fame.

Could The Specialist have been born in 1912? The Life says he told the yarn “off and on to friends [and] actors.” An uncredited story in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 11, 1929 (Dispatch), dates it as 17 years told, i.e. from 1912. Harold W. Cohen in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 16, 1930, tells readers that Sale and an “up-and-coming comedian” named William Frawley were idly trading reminiscences about their boyhoods. (Is that the same William Frawley who capped his long career in I Love Lucy? Could be. Frawley, who was just two years younger than Sale, had an act in Denver for a while. I can’t pin either down to a specific date, though.) Sale told a tale about Lemuel Putt, supposedly a carpenter in Urbana known for his outstanding work in building outhouses. And then one of the two said something like, “you should use that in your act.”

Not likely. In fact, The Life details how careful Sale was not to use the story in his act, but practice it as he told it to men’s clubs, and small gatherings, and – at invitation-only parties – to men and women alike. It wasn’t until “the early twenties” that actor Frank Bacon urged him to take it public with an enthusiastic “You’ve got something there, Chic.” Sale “built the story, paying the same attention to detail that Lem had paid in constructing his small building.”

The monolog “swept Rotarian United States,” the Rotarians being a men’s organization with outposts everywhere. Perhaps more satisfyingly, the tale about Lem Putt’s specialty had a big New York debut at the Lambs Club in New York City, The Lambs being the preeminent social club for actors. The Lambs often put on fabulous collections of member’s performances. For this one Paul Whiteman’s band, then giants of jazz, provided background music. Unfortunately, no date was given, nor can I find one. The Lambs, by the way, were also all male.

No matter that every house needed an outhouse in the days before indoor toilets, and every man, woman, and child used them. The very idea of talking about such an everyday necessity in public before a mixed group was near unthinkable. Outhouses were in the category of “earthy” material and so was as risque as blue language or a bare female thigh. Alicia Meyer’s Hollywood Essays quotes Will Rogers on The Specialist: “It’s like reading that the Archbishop of Canterbury has been caught at a night club.” (The quote is not sourced and appears nowhere else online, but it seems to encapsulate the feeling of the times.) Certainly that was part of the speech’s appeal. This was true situational comedy: no jokes, just a series of recognizable and relatable human flubs and failures, but on a subject previously considered untouchable.

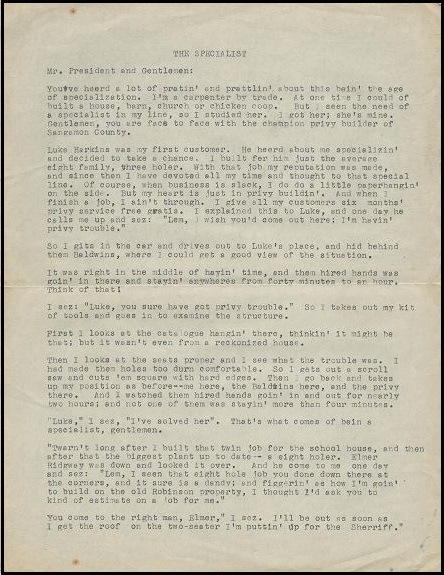

Sale gave his monologue in front of men’s groups for years, reputed by the newspapers to make as much as $1,000 per week alongside his regular income. He was in constant demand due to phenomenal audience response. “People doubled up and rolled off their chairs,” reported the Dispatch. The print edition makes clear that the text is a speech to a men’s organization: it opens “Mr. President and Gentlemen.” Sale had long entertained mixed audiences of friends with the tale, but society’s preference for protecting women from even the slightest hint of impropriety remained strong long after the Roaring Twenties.

A short monologue wasn’t difficult for a trained actor to memorize. Another someone might also memorize it or, more likely, find a person trained in shorthand to transcribe the words. Typewritten copies of The Specialist circulated across the country. At the time unpublished material was not copyrightable; anybody could type the complete text of a monologue and pass the copies around, as many copies as they wanted, foreshadowing the cottage industry of bootlegging recordings of rock groups in the 1960s, but legally.

Even the bootlegs mostly were distributed to men. The Life says that Chic kept being discouraged by friends when he broached the idea of printing it himself.

Author Fred C. Kelly had advised: “It will never go over , Chic, and I believe it will do you no good to publish it. Instead it might well do you harm.” He had turned to cartoonist H. W. Webster for advice and Webby agreed with Fred. “Tell it, don’t try to print it,” was his opinion.

According to the story in the Dispatch, one of those bootleg copies found its way to R. J. Seeman. (He was a circulation manager for the rival St. Louis News-Democrat, a fact that the anonymous reporter discretely refrained from mentioning.) Seeman passed the bootleg onto to W. S. McClevey, local manager of the Western Newspaper Union. They saw the possibilities of getting the work into publication to obtain copyright protection, and convinced Sale this needed urgently to be done. “Either publish it or lose it!” was the way The Life said they melodramatically put it. Within a week The Specialist Publishing Company was born, split 50/50: 50% to Chic, 50% divided by the other two.

Although Sale must have had access to the bootleg transcript, he spent weeks while on the road rewriting and honing the script. Scripts were all he knew and a stage script was what he turned in.

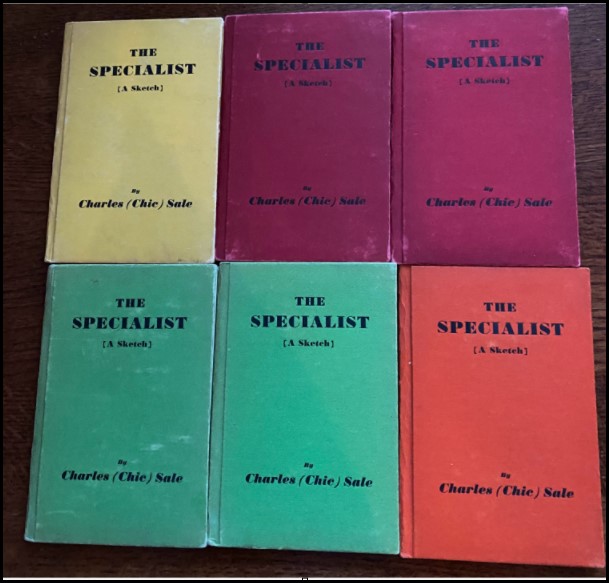

Seeman and McClevey printed the manuscript just as received in January 1929 and spent extra money to create a trial printing in a rainbow of colors.

Collectors should go panting after this hitherto unreported first edition, because it is literally stated as the first edition.

You’ll probably never find one because the reality is that as soon as Sale read his sketch in print form he realized that it simply didn’t work. “We soon learned that telling a humorous story and writing it are two different techniques,” Marie wrote. Fortunately, Sale was booked for a long run in Los Angeles, where every night after his shows he could hand a “much-scribbled manuscript” to a chorus girl who knew typing. “Would you believe it,” Sale said, “I’ve been telling this story for more than ten years and it took me two whole months to write it!” He took extreme care to ensure that nobody could say it was dirty in any word, line, or page.

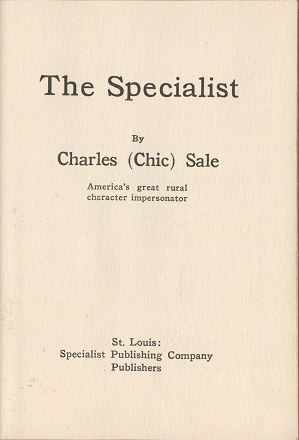

Sale’s two partners dutifully printed up the new version, dropping the pretty colored boards for a drab brownish tone and sinking their money into 5,000 copies of a small 32-page booklet in hardcovers. Their need to recover their expenses showed. At a time when a 300-page mystery novel sold for $2.00 they had the audacity to charge $1.00 for this trifle – the text covered only 16 of the 32 pages, enlivened by several full-page illustrations (probably by Percy Vogt, who wouldn’t get credit until the sequel).

Everyone told them that such a shocking price would lead to failure. Everyone was wrong. The price didn’t matter. The booklet immediately sold, and then soared into uncharted territory. Pricing the book at a dollar apparently took the sting off the subject; at that price it was a work of art. So spectacular were sales that they soon issued an edition in leather covers for a eye-popping $3.00. Henry Ford ordered a batch of them, said the Dispatch. By October, when the article appeared, the book’s dust cover proclaimed that over 500,000 copies had been sold.

Marie never mentions money in The Life. The Dispatch article was not so discrete. It revealed that the deal was jiggered so that the people who put up the money got the lion’s share of the profits over the actual writer. There in a nutshell is the history of the publishing business. Chic’s share topped $10,000, which probably seemed terrific even to someone already making four-figures weekly. But Seeman and McClevey made $50,000. Each.

And the book kept on selling. Marie quotes wounded cries from the book establishment, like these from Harry Hansen of the New York World.

The ways of the public are inscrutable… Here are [a list of serious authors], and here is the whole reading public falling head over heels for a volume of less than a hundred pages on the architecture of the outhouse. Let’s go to the ball game!

It does not seem good tactics to place a pamphlet on best seller lists preceding important works of serious content. There should be a subsidiary list for trivia…

Sale’s sales embarrassed those of the writers striving for those lists as well. Kenneth Roberts, who would go on to super fame and mandatory high school reading with his novel Northwest Passage, saw no such fame and gain with his first novel, according to Petri Liukkonen:

In I Wanted to Write (1949) he bewailed that Chic Sale’s The Specialist, about building outdoor privies, had led the best-seller list for forty consecutive weeks, while he can’t find Arundel on any list of bestsellers.

The reading public deluged the Specialist Publishing Company with mail from “sorority houses, literary guilds, factory groups and women’s clubs, university professors, politicians and governors.” The St. Louis office had to be enlarged three times and Sale, appearing on Broadway, set up a New York office that answered every letter.

A 1930 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, almost a year later to the day than the Dispatch article, celebrated Sale’s success at selling over 1,000,000 copies. The Specialist had catapulted him into one of the most-wanted men in showbiz, making 1930 as much a banner year as 1912.

In 1930, Sale …

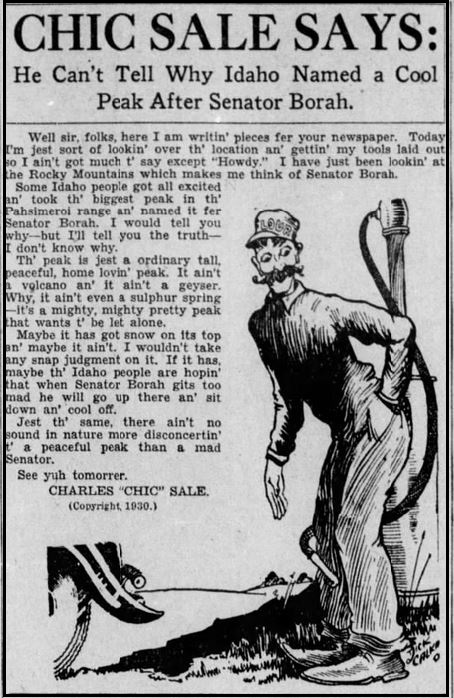

- started a daily newspaper column, syndicated to at least 65 papers.

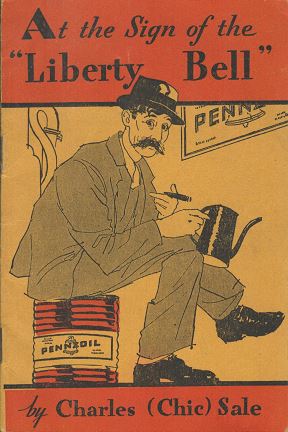

- was signed to a radio show on the CBS network, The “Liberty Bell” Filling Station. Sponsored by Pennzoil, Sale would voice the part of “Wheel” Wilkins, owner of the Liberty Bell Service and Filling Station, whose image appears at the top of the page on the right. (The August 1930 Radio Digest, available online, contains a complete script.) Pennzoil also released a promotional brochure featuring Sale, with an article purported to be by him. (Celebrity articles were often written by PR men.)

- filmed the book as a movie short titled Lem Putt, The Specialist, of which not much is known about.

- Wrote a song called “I’m a Specialist” that condensed the book into three minutes. Frank Crumit, who was known for comedy songs, recorded it in 1931.

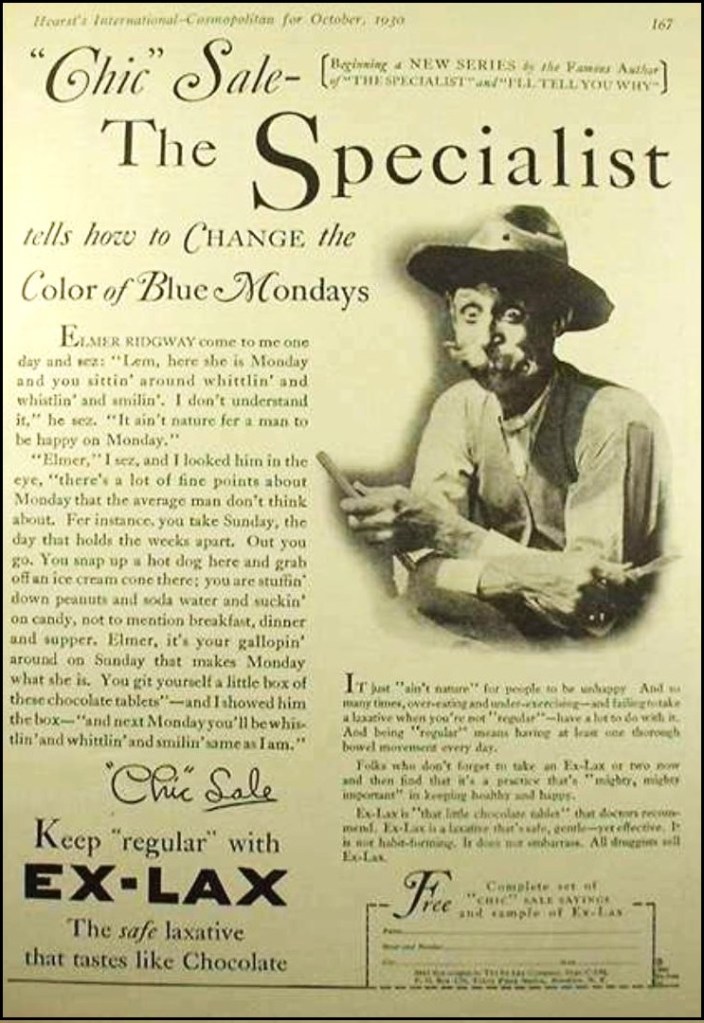

- agreed to use Lem Putt as a character in an ad campaign for Ex-Lax. (Seriously. This is real. Somebody at Ex-Lax had an interesting sense of humor.)

- starred in a Broadway show called “Hello, Paris!” in character as Lem Putt, The Specialist.

- was thought so highly of that he received plaudits in biographies of other comedians! J. R. Milne, in a syndicated history of the Amos ‘n Andy radio show, dropped this tidbit. “You know who Chic Sale is. If you don’t, where have you been all these years? Chic could make a ventriloquist’s dummy laugh in Boston while the ventriloquist was visiting friends in San Francisco.”

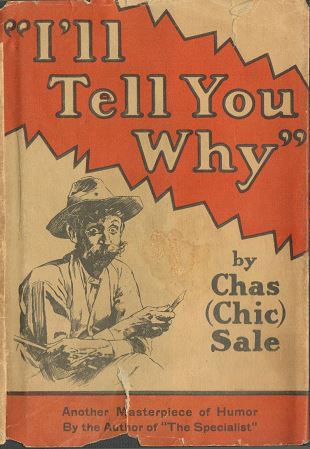

- and put out a sequel to The Specialist, I’ll Tell You Why.

This decision, urged upon Chic by Seeley and McClevey, was a mistake. Nothing could stop sales of The Specialist except more of the same, written in a single month and not perfected line by line by a dozen years of audience response. The book stalled before a second printing. Sale responded in June by buying out his partners and taking control of the company.

With vaudeville and Broadway turning iffy in the Depression, Sale soon moved to California, where he kept a goat at his handsome Beverly Hills house to remind him of home.

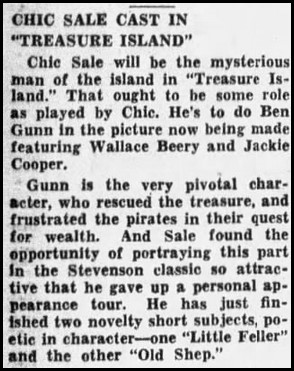

He had made an unreleased talkie as early as 1927, billed on IMDb as possibly the first sound film in Hollywood, but his forte was his verbal rural impersonations. That made him a good fit in the suddenly mature talkies era. He gained headlines just for being cast in the lavish 1934 production of Treasure Island.

Recognize him? He’s the bearded one in the middle.

He piled up an additional three dozen credits to good reviews in the 30s while finding time to tour the country on stages.

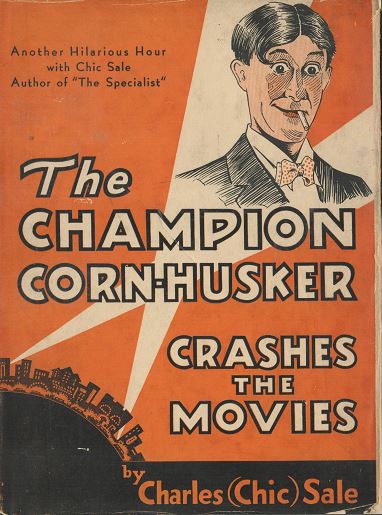

The move west was reflected in another short book called The Champion Cornhusker Goes to California, whose release was again swamped by all Sale’s other work.

As a truly national star, newspapers across the country followed his progress day-by-day when he fell ill with pneumonia in 1936. No recovery was possible; Chic died in November at the early age of 51.

The Specialist continued to sell long after Sale himself was forgotten by most. Matthew Sale Brown’s website offers this astonishing statistic about The Specialist.

Now in its 26th printing, it has sold over 2,600,000 copies worldwide. It has been translated into 9 languages and published in 12 countries.

Rustic American humor working in other countries? Well, outhouses were universal.

Humor historians have to remember that two bodies of humor, urban and rural, have always existed through American history. Hee Haw debuted just after the Smothers Brothers. The Blue Collar Comedy Tour commenced in January 2000 and The Original Kings of Comedy movie was released in August 2000. The Specialist appeared the same year as books by Forgotten Humorists Will Cuppy and Corey Ford as well as several New Yorker humorists, proving that every type of humorist has an equal chance to be lost to history.

Aside 2: some advice to collectors.

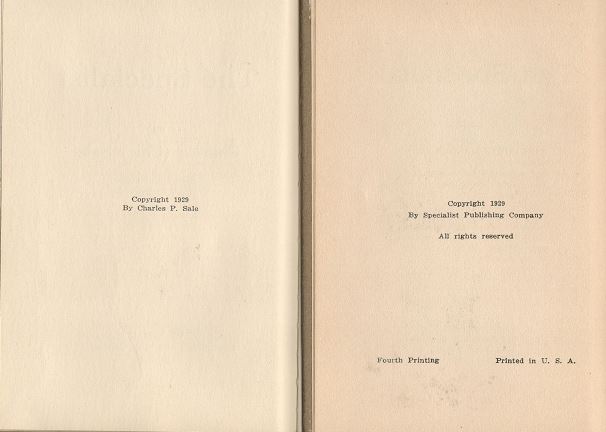

The true first printing, as shown above, will include the words “A Sketch” on colored boards and “First Printing” stated on the copyright page. Any in circulation will be a real find.

Those findable online almost always have dull brown boards and a printing state on the copyright page.

Except what is probably the first, general release, printing of 5,000. That seems to have no printing stated at all. I don’t know whether it came with a dust jacket. The following points are in its interior, compared to the Fourth Printing, otherwise the earliest I’ve seen.

Two subtle changes. “America’s great rural character impersonator” is replaced by “America’s great rural character actor.” and the stacking of the publishing information is different: “Publishers” goes to the top line in italics; “St. Louis” drops to the bottom line and adds, “Mo.”; the address “1911 Pine Street,” now a permanent office, is inserted as the third line.

Another giveaway is that the earlier edition is copyright to “Charles P. Sale,” but later printings assign the copyright to the “Specialist Publishing Company.”

Other points are the inclusion of a poem, “Doc Sale’s Boy,” by John D. Wells, originally in the Buffalo Courier-Express, before the Foreward in the fourth printing. The poem first saw print in the March 28, 1928 edition of the paper, meaning it was written before The Specialist was released. I think nothing better indicates the level of Sale’s fame more than this poetic tribute to him.

Additionally, the Foreward, anonymous in the earlier printing, is now signed by publisher W. S. McClevey.

The fourth printing is wrapped in a dust jacket. It must be later than the 5,000-copy printing, or even a brand-new addition, because the blurb “Hilariously Funny” is taken from a tiny unsigned article in the Dispatch from February 13, 1929.

Marie reprints a letter from the Doubleday-Doran Book Shop in St. Louis, detailing their purchases of copies. Three lots of 25 each in February, five lots peaking at 100 in March, totaling 225, and eight lots in April, the smallest 50, totaling 510, an astounding 810 copies from a single bookstore. They also ordered 10 copies of the $3.00 leather-bound version. “Our average sale is three copies to a customer. I cannot recall any book within the last ten years that has had such an amazing sale. It is unbelievable!” wrote the manager. He also states that the book was only in its third printing, thereby dating the leather-bound variant at least that early.

The Eighth Printing has a large hexagonal block on the dust jacket reading “More Than 300,000 sold.” The Tenth Printing raises that to 400,000, and the 12th Printing to a Half Million. The Fourteenth Printing trumps them, announcing that the book had passed the million mark. And the Nineteeth Printing, from 1956, move the needle off the scale to an incredible “More than 2,000,000 Copies Sold.” The sales include those from eleven other countries listed on the back cover.

Bibliography of Humorous Works

- 1929 – The Specialist (illustrated by Percy Vogt, uncredited)

- 1930 – “I’ll Tell You Why” (illustrated by Percy Vogt

- 1930 – At the Sign of the Liberty Bell (illustrations uncredited)

- 1933 – The Champion Corn-Husker Crashes the Movies (illustrations uncredited)

You must be logged in to post a comment.