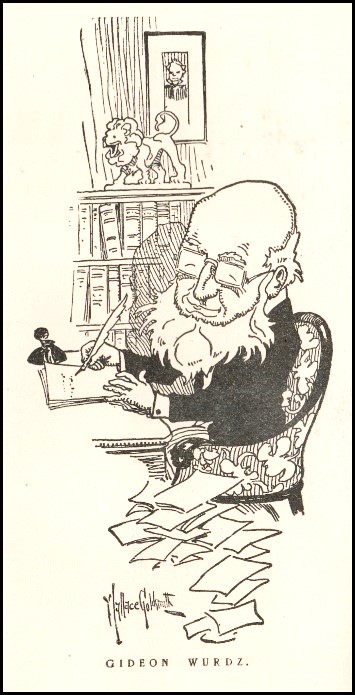

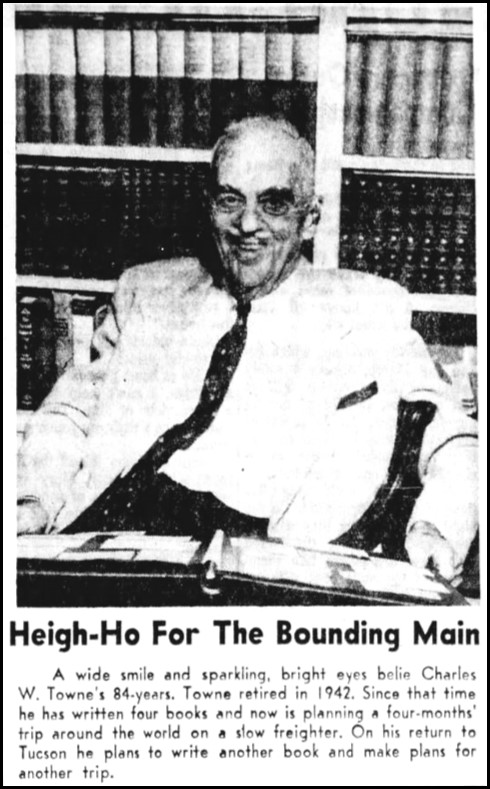

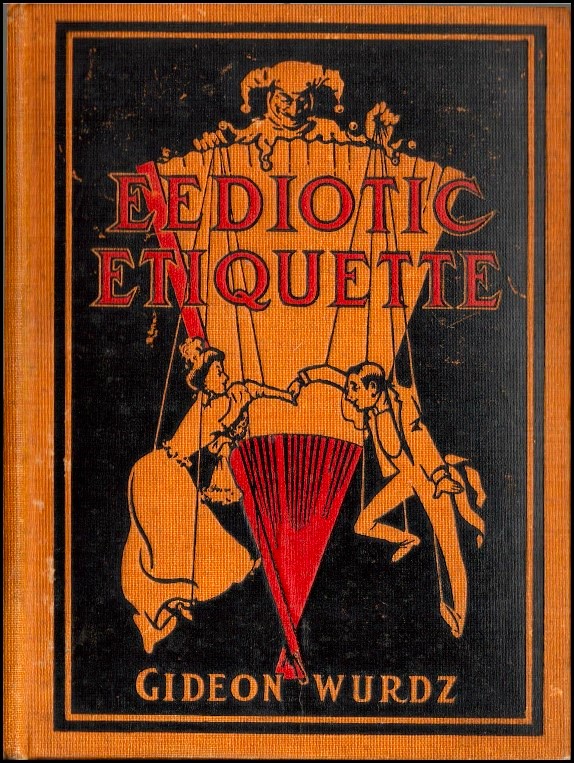

“GIDEON WURDZ” (Charles Wayland Towne) Author of “Eediotic Etiquette.” says the 1906 publicity picture. Gideon Wurdz. “Giddy on words,” get it? Charles Wayland Towne might be the most forgotten of my Forgotten Humorists. Yet he was famous enough to earn a newspaper photo. Very rare in that era. I spend huge amounts of time trying to dig up contemporary portraits and here’s one presented to me, complete with real name as well as pseudonym. The man must have been a star in 1906 but he doesn’t even rate a Wikipedia article today. Perfect for this site. I knew nothing about him either, to be honest. All the better then. Resurrecting names lost among the thousands of books in my collection means that I get to learn about them and pass their lives to you. And what a life I uncovered.

Towne was “the funny man” of Brown University’s class of 1897. He went straight to work for the New York Times and then got hired by the Boston Herald to cover the Spanish-American War. In 1902, Buffalo Bill Cody brought his Wild West show to Boston, which included a re-enactment of Teddy Roosevelt’s charge up San Juan Hill in the war. Towne, who was in Cuba – Cody certainly wasn’t – asked to be part of the show. He afterward wrote such a terrific article that, in a living embodiment of a cliche, Cody hired him away from the paper. First, though, Cody asked Towne to be his guest on a western hunting trip. Back at the turn of the last century, that was a jaw-dropping offer for an adventurous young man. Apparently the trip was just a way of feeling him out as to what he could do. Cody soon learned that Towne could do anything in writing, penning publicity articles and editing a newspaper Cody owned.

Cody owned a lot of things, including a hotel. After the manager left because of illness, Cody turned the hotel over to Towne. That he couldn’t do. He returned to the East and spent a year “on the grubline.”

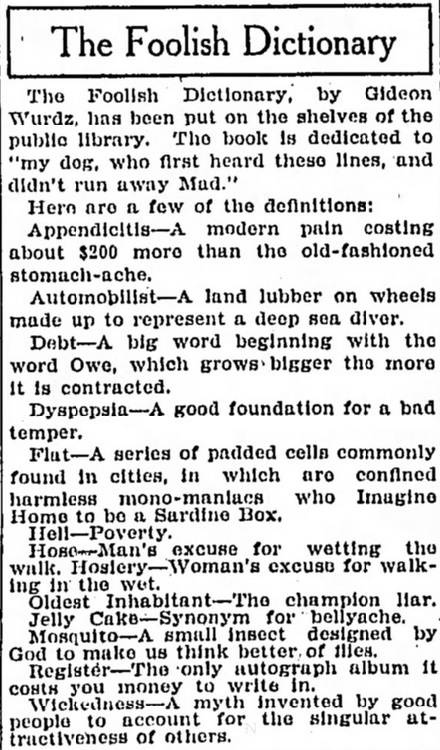

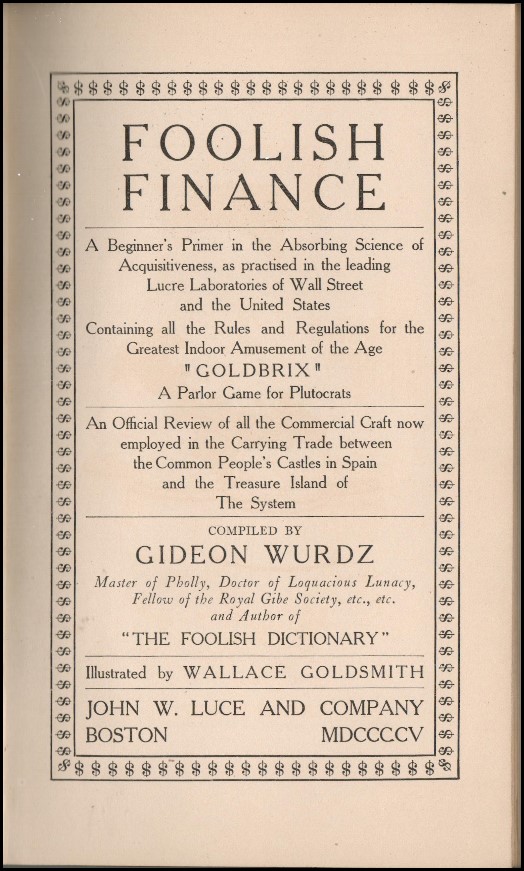

“Broke and hungry,” in his words, he churned out a little book called The Foolish Dictionary in just 23 days. Though obviously just another knockoff of the Devil’s Dictionary newspaper and magazine pieces that Ambrose Bierce had showered the public with for years, Towne, or “Gideon Wurdz, Master of Pholly, Doctor of Loquacious Lunacy, Fellow of the Royal Gibe Society, etc. etc.” beat Bierce to publishing an actual book.

The yuks started early. Originally announced for February, the advance reaction led the publisher to hold off its release until April 1. Or so they said. Their press releases also claimed that contributions were being garnered from the leading humorists in the country. Would be historians: beware of press releases being published as news.

Press releases mostly dispatched their news to indifferent readers. This one didn’t. Eventually. What made this book go viral, or the equivalent, is unknown, but by June newspapers across the country found the little volume and got caught up in a fit of jollity. Few could resist throwing out a few quotes.

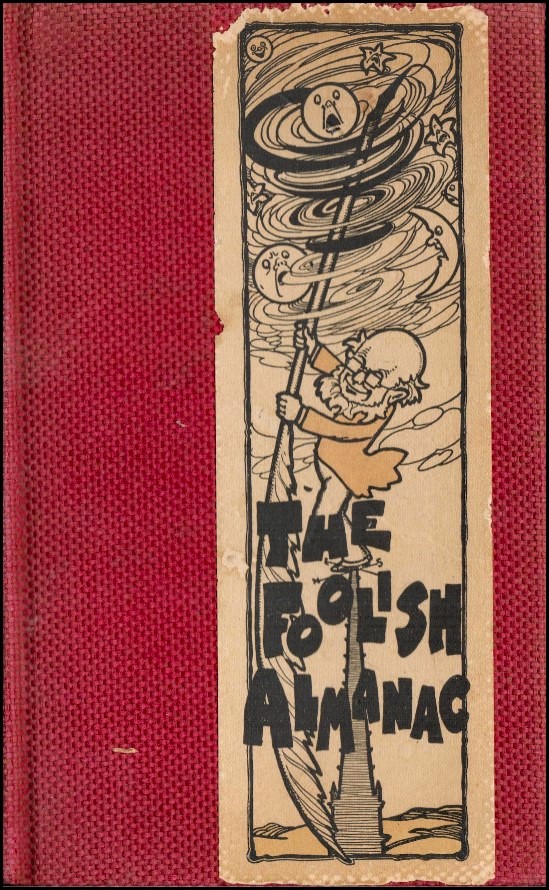

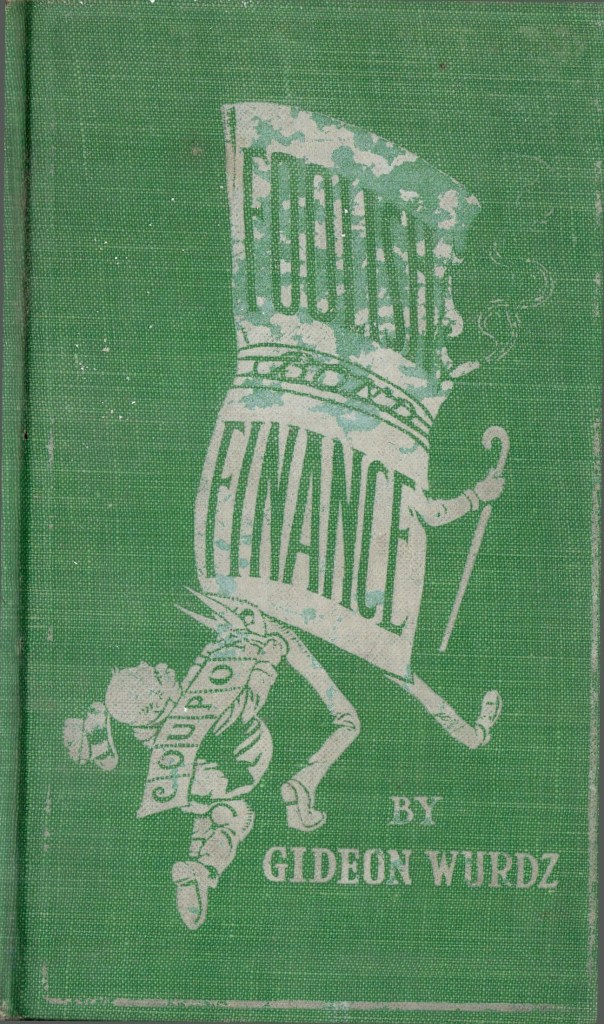

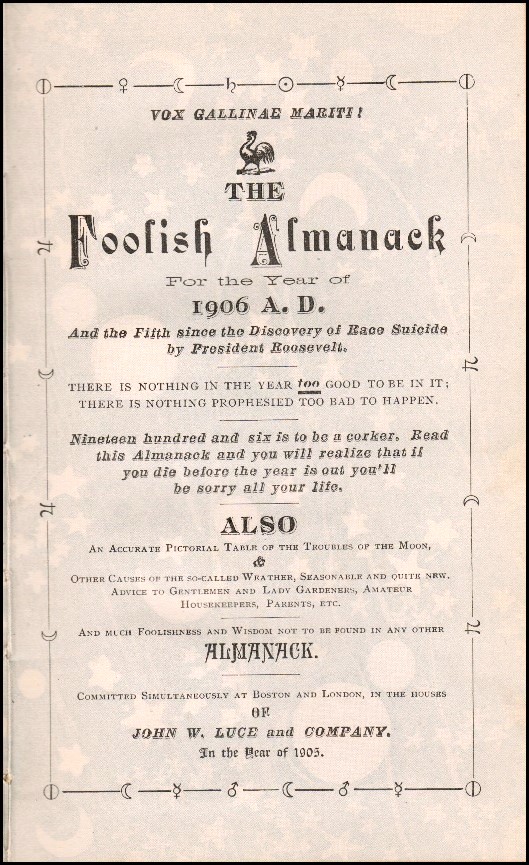

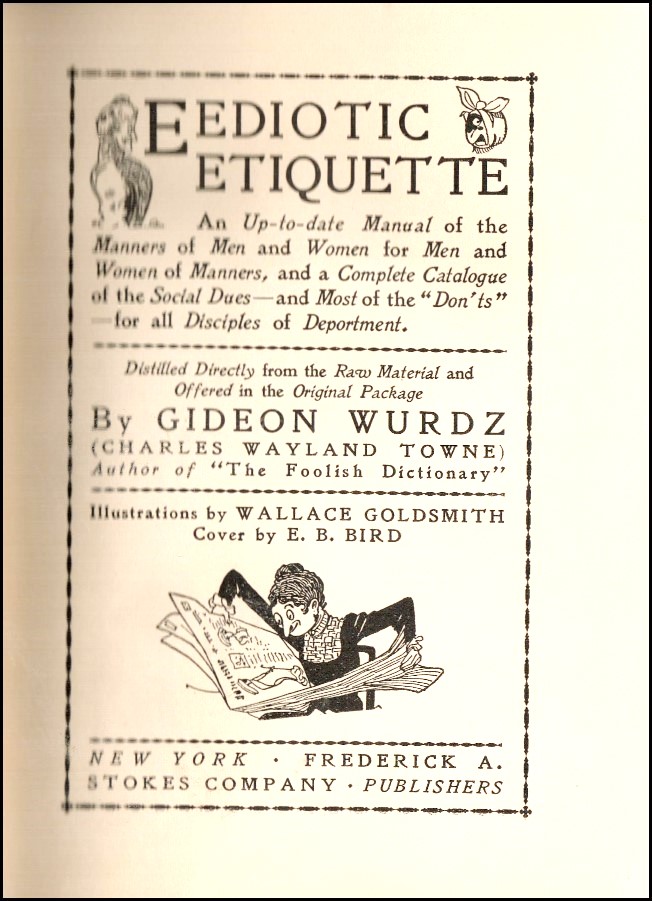

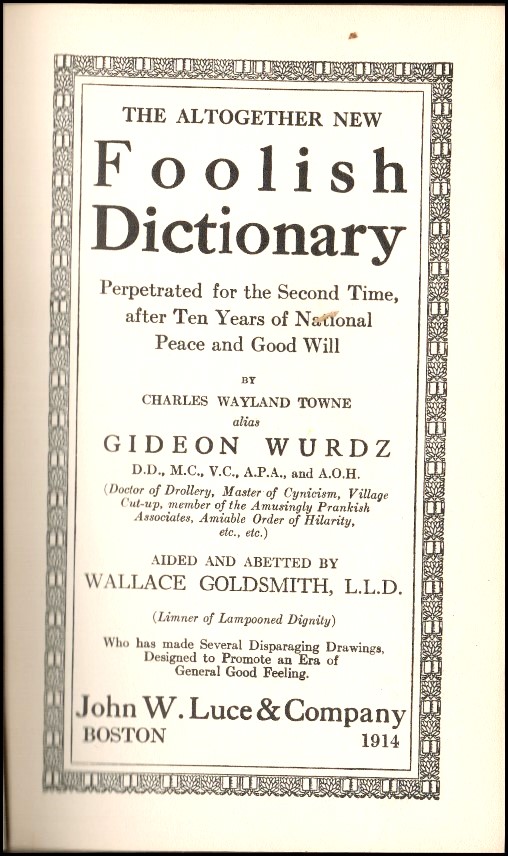

The public swarmed. Towne claimed the book sold 193,000 copies and took the hint. Four more books by Gideon Wurdz appeared in the next two years: The Foolish Almanac and Foolish Finance in 1905; Eediotic Etiquette and The Foolish Almanac 2nd in 1906. The picture at the top of this page is a publicity shot of Towne from 1906. Notice that no secret was made of his alternate identity. (The New Foolish Dictionary, probably ground out in a lull between jobs, made a belated appearance in 1914.)

Just as Towne gave Wurdz an elaborate set of titles, as British academics commonly did to show off their accomplishments and expertise, he had the publisher fashion a title page in the style of early 19th century works. Those normally featured long and literally wordy titles that served as a precis and introduction to their books, in an era when every bookseller might have a different selection.

The second Foolish Almanac (“For Anuthur Year” – really 1907) looks like it’s written by an illiterate. While that might be appropriate for a “Foolish” book, the joke goes deeper. The reference to the Karnagy Speling Skool shows that the whole page was a spoof of the Simplified Spelling Board that Andrew Carnegie launched in 1906. Simplified spelling was one of those bright ideas embraced by well-meaning people who wanted to make it easier for the tens of millions of immigrants pouring into America to learn English. If through could be spelled “thru” and the silent “e” knocked off of give, have, and twelve, some of the idiocentricities of English could be eliminated. That this would make all the works ever published in English obsolete was a minor issue compared to the future value of the changes. Wasn’t the country going through the greatest period of change the world had ever seen in any case?

Illustrator Wallace Goldsmith (“Limmer of Lampooned Dignity”) made this clear with his frontispiece, a new zodiac surrounding what is obviously a robot, although that name had not yet been invented. Goldsmith had surely seen some of the clockwork automatons featured in stage performances or scientific exhibitions. Even that early, robots symbolized the future. (For more on early proto-robots, see my site on my book, Robots in American Popular Culture.)

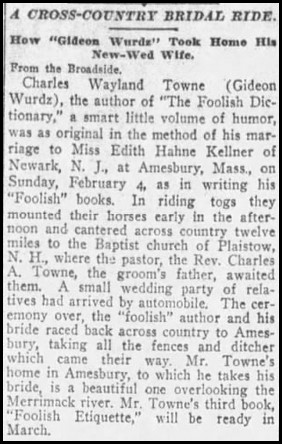

Towne was in the money. From down and out, he was now a prosperous member of the middle class, owner of a “beautiful home” on the banks on the Merrimack River in Amesbury, MA. Middle class? Possibly upper class, or aspiring to it, judged by this account of his marriage in 1906. He and Edith would have one son, Richard.

Amesbury is at the northern tip of Massachusetts. Towne stayed away from large cities, loving the outdoors and rugged American beauty. With his newfound riches, he started as well as edited several newspapers in New England, including one called Among the Clouds, “the first and only newspaper … on any mountain summit in the world,” that summit being the famously windy one on Mt. Washington in New Hampshire.

Too old for World War I, he was instead recruited to organize entertainment for the troops, books over 175 groups in France. Including himself. He and three friends started a barbershop quartet that “went over big.” He stayed active in that community for the next half century.

Towne was lured back to the west in 1920 and stayed there the rest of his life. When one goes to Brown University, one has classmates like a Rockefeller. This one – John D. Jr. – helped make Towne the publicity director of Anaconda Copper and later of Montana Power. He wrote not only about the companies but about the glories of Montana, with titles like Her Majesty Montana and Western Montana: a land that enchants the traveller, enriches the settler and inspires everyone.

When he retired he moved to Tucson and got serious about the history of western America. Three major works appeared from the University of Oklahoma Press, one each on sheep (Shepherd’s Empire (1945), swine (Pigs from Cave to Cornbelt (1950), and cows (Cattle and Men (1955). Each book was written with his cousin, Edward Norris Wentworth, who was head of Armour’s livestock bureau.

When he was 84, he and his wife spent four months on a freighter traveling the world.

That other book was planned to be a biography of philanthropist George Peabody. He was good on his word; when Towne died at the age of 89, he left behind a never-to-be-published manuscript. Want to read it? Towne’s papers can be found at, where else, the Peabody Museum Archives at Harvard.

Bibliography of Humorous Works

- 1904 – The Foolish Dictionary (illustrated by Wallace Goldsmith, uncredited)

- 1905 – The Foolish Almanac (illustrations uncredited, probably Wallace Goldsmith)

- 1905 – Foolish Finance (illustrated by Wallace Goldsmith)

- 1906 – Eediotic Etiquette (illustrated by Wallace Goldsmith)

- 1906 – The Foolish Almanac 2nd (illustrated by Wallace Goldsmith)

- 1914 – The New Foolish Almanac (illustrated by Wallace Goldsmith)

You must be logged in to post a comment.